Activists Are Pushing Back Against Tech Platforms That Quietly Empower Hate Groups

As the cofounder of Disqus, one of the biggest services powering the comments sections of websites, Daniel Ha has seen his share of uncivil discourse over the years. But since the 2016 election, the San Francisco-based CEO concedes there has been a rapid increase in conversations that veer from basic mean-spiritedness to polarized accusations and outright slurs. “Oh, it’s much bigger now,” Ha tells Fast Company. “It is absolutely related to what’s going on in society and this [presidential] administration and the perception of it.”

Disqus is one of a growing number of tech platforms under scrutiny for the websites and organizations they do business with. As the speedy downfall of Fox News pundit Bill O’Reilly recently demonstrated, post-election liberal activist movements are getting much better at publicizing their causes and marshaling financial pressure, and no company with money to lose is off the hook for the relationships it maintains.

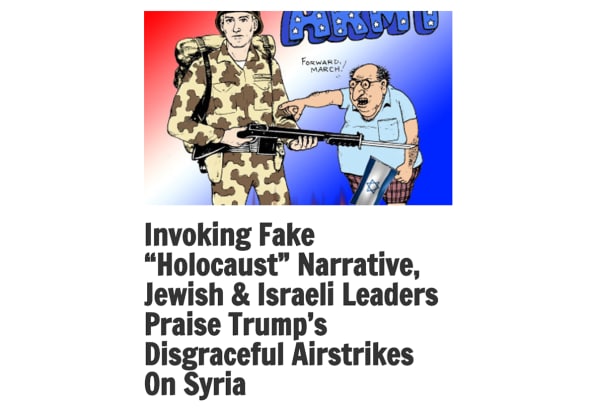

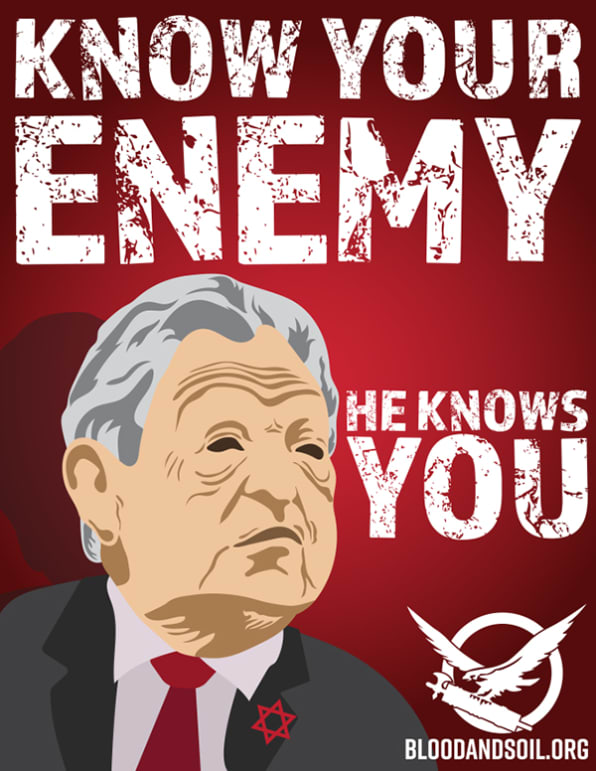

That includes not only comment platforms like Disqus, but any entity that powers the various levels of internet infrastructure—from payment providers like PayPal, to web-hosting services like GoDaddy, to social media giants like Facebook. Activists have figured out that while they can’t make everyone behave civilly, they can go after the advertisers that fund uncivil conversations and the internet services that keep them going. The end goal is to effectively silence incendiary organizations of all kinds, from white supremacist groups like American Renaissance to black supremacist ones like Nuwaubian Nation Of Moors, from the Holocaust-denying Realist Report to the anti-Semitic and anti-gay site The Right Stuff. Such groups have long been online, but now the companies that give them a platform are being taken to task.

The increased pressure brings up a lot of uncomfortable questions for tech firms. At what point does preserving civility—and possibly even safety—trump Silicon Valley’s libertarian philosophy that the internet must remain open, that information wants to be free? Is online free speech absolute or is there an internet equivalent of yelling “fire” in a crowded theater? Can companies separate commerce and business relationships from moral judgments? Is it sufficient to take action about unsavory clients only after people come complaining?

And finally, can we just ignore all this and hope it goes away? Increasingly, the answer appears to be no.

The easiest course is to reserve action for when content posted on a website actually violates the law, such as criminal transactions or depictions of child pornography. That leaves a lot of unsavory material in the acceptable zone: swastikas, burning crosses, disparaging slurs against women or minorities. And companies, forced to defend their reasoning for leaving such content up, typically employ a free-speech argument.

“We strongly support the First Amendment and are very much against censorship on the internet,” writes Ben Butler, director of the Digital Crimes Unit for GoDaddy, in an email. He adds that, “if a site promotes, encourages, or engages in violence against people, we will take action.”

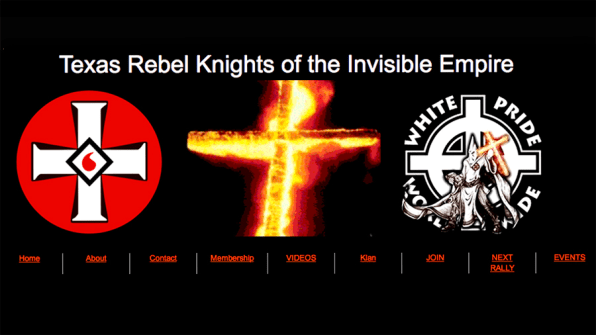

But while the First Amendment may be a motivator for GoDaddy, it is not a legal requirement for it or any other company, says Sophia Cope, a staff attorney for the Electronic Frontier Foundation. “Can they choose who their customers are? Can they have content guidelines? Sure,” says Cope. GoDaddy hosts at least seven Ku Klux Klan sites—all of which the company has judged to be in compliance with its guidelines.

The Atlantic captured this video of an NPI event in November in which Richard Spencer drops Nazi terms like “Lügenpresse” (lying press).

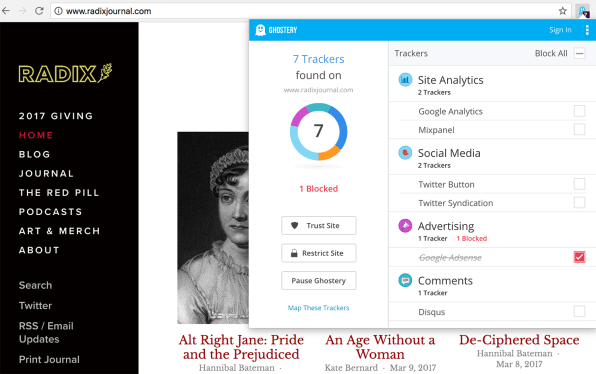

What slips by such guidelines are blanket statements that vilify ethnic or social groups, like Jewish or gay people, but fall short of a clear incitement to violence. For instance, they are common—though obscured by a veneer of intellectual discourse—on Radix Journal, a website hosted by Squarespace. Consider an essay on the site that warns against alt-right cooperation with Jews:

One might consider the analogy that our opposing forces act as a giant knife, cutting into the heart of the nation. The coterie of Leftists, anarchists, degenerates, homosexuals, self-interested elites, and others of our race make up the bulk of the blade. But with what preponderance are Jews found at the razors edge!

Radix Journal is run by the white supremacist National Policy Institute, whose website is also hosted on Squarespace. Another essay on the site, by neatly dressed, Nazi-quoting NPI chairman Richard Spencer, argues for the intellectual inferiority of black people. Squarespace even powers the online store for Radix Journal, where Aryans can pick up an alt right-themed T-shirt or a “Trump Deportation Force” poster for under $ 30.

Of course, this being the internet, some of the most disturbing content on those sites lives within the comment sections. That brings us back to Disqus, which hosts comments for Radix as well as NPI, commonly featuring statements like this:

Taking “measures against” Jewish influence is too little too late. When the goblins are already inside your home, eating from your pantry and fingering your children, you are several degrees past the point where forming a new investigatory commission is warranted.

We contacted tech companies about their connections to such disparaging content. Squarespace declined to comment. Disqus’s Kim Rohrer, who holds the title of “VP of people & culture,” said the company cannot discuss whether any specific site is being reviewed for violating policies. However, regarding a list of 19 controversial websites that included Radix and NPI, Rohrer said by email, “I can tell you that most of these are under review and we have explored technical and policy solutions with them.”

Some companies are a little more willing to show their discomfort with controversial content than others. When we began our research, donations to Radix were handled by an online payment processing service called Donorbox. (It has since switched to another provider, called Memberful.) Charles Zhang, founder of Donorbox, expressed alarm when we informed him about Radix. “We are deeply disappointed and dumbfounded that a white nationalist movement spearheaded by Richard Spencer has a following in the United States,” he wrote in an email.

Dumbfounded is a frequent reaction by companies that host sites, comments, payments, or ad-placement services for incendiary websites. The web is becoming ever more automated, and online service companies may have no idea who their customers are until someone else comes asking questions.

When Do You Call It Hate?

Radix Journal is just one of over 280 sites that a group of activists has flagged as being linked to hate groups identified by the Southern Poverty Law Center. SPLC, founded in 1971, tracks such groups in the United States, everything from neo-Nazis and KKK chapters to black separatist groups, to a few U.S.-focused Islamist extremist groups (most are based overseas), to anti-Muslim organizations, to groups that oppose gay rights.

The list of such groups grew from 599 in the year 2000 to a high of 1,018 tallied in 2011. The latest count is 917, with the number of militia-type groups and KKK groups in decline but the number of groups considered anti-Muslim having doubled in just a year. The listing is used as a reference by other organizations and some companies that aren’t directly tied to SPLC.

“Hate groups increasingly function only online,” says Heidi Beirich, director of SPLC’s Intelligence Project, which researches hate groups. “Just like in the real world, people are moving their social activities from real-world events to online events; we’ve got a follow-on there.”

Right-leaning groups—including Christian conservative ones—often cry foul at the “hate” designation, saying they are unfairly painted with a broad brush because they hold differing moral or political views. “I think some of them, some people might say that they’re just conservative,” says activist John Ellis, who independently helped research the list of companies providing tech services to SPLC-designated hate groups.

But Beirich says that argument doesn’t hold up for groups that reject the basic idea that people should be treated equally. “What we’re looking for in the ideology is, does the organization consider an entire group of people—black people, gays, Jews, whatever it is—to be lesser,” she says. Examples she names include the Nation of Islam calling all white people “blue-eyed devils,” or conservative religious people saying that gay people are “diseased.” A group doesn’t have to advocate violence to make the list.

“A lot of times the websites are very clean, but the books they publish or what their leaders say are very different,” says Beirich. “If we listed everybody who says homosexuality is a sin or is against gay marriage, you’d be seeing tons of churches, but obviously our criteria is more narrow.” There may be room to argue over individual listings, but many entries pass the sniff test for prejudice. Among them: The American Nazi Party and a dozen sites with “KKK” in their name.

As Ellis characterizes it, these and other incendiary sites are business partners with tech companies such as Disqus, GoDaddy, and Squarespace. The Boston-area entrepreneur was surprised on February 3 to see an ad for his engineering firm, Optics for Hire, appear on Radix Journal. Ellis didn’t choose to advertise on Radix. It happened because an automated ad network (he believes it was Google’s) sold targeted ad space on the site in the tenths of a second between when Ellis clicked a link and when the page loaded in his browser. Ellis may have seen the ad because his connection to the industry featured prominently in some online advertising profile. His disdain for racism did not.

The Breitbart Effect

Online nastiness is not new. “All the internet communities, online discussions, that entire beast has always been fairly chaotic,” says Disqus’s Daniel Ha. But pressure on tech providers has grown in recent months, triggered by a fiercely polarizing election and the rise of Breitbart News from a fringe alt-right conservative site to a major internet destination, whose former executive chairman, Steve Bannon, became President Trump’s chief strategist.

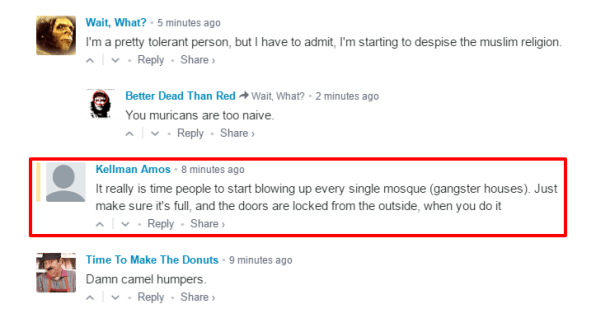

Breitbart is not considered a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center. But SPLC did release a study indicating a sharp rise in the use of the word “Jewish” as a slur in article comments, which are hosted by Disqus. Hateful reader comments and harsh Breitbart articles (such as “Birth Control Makes Women Unattractive and Crazy“), have fueled a large anti-Breitbart advertising boycott effort from a group of anonymous activists called Sleeping Giants.

They and their Twitter followers have gone after advertisers on Breitbart, tweeting screenshots of ads next to controversial articles and inflammatory comments, such as, “It really is time people to [sic] start blowing up every single mosque (gangster houses).” Sleeping Giants’ campaign has convinced over 2,000 companies and organizations to blacklist Breitbart from their automated buys on ad networks. It also played a role in the O’Reilly Factor ad boycott that preceded the recent firing of Bill O’Reilly. A few ad networks, including Rocket Fuel and major player AppNexus, have unilaterally blacklisted Breitbart for all their clients.

“My inlaws are immigrants from Egypt, and they’re Muslim, and I was offended by the initial travel ban,” says Ellis, referring to President Trump’s now-blocked executive order restricting travel from seven predominantly Muslim countries (not including Egypt). “I was interested in the work Sleeping Giants was doing using free-market principles to defund a news source that had promoted this narrative that immigration was a problem.”

Ellis started by targeting Disqus, which hosts comments on not only Breitbart and Richard Spencer sites, but also The Right Stuff, anti-Muslim site American Freedom Defense Initiative, and the white-nationalist online journal Occidental Dissent, among others. Ellis soon encountered another activist, EJ Gibney on Twitter, along with two others who remain anonymous for fear of drawing attention from the hate groups.

They began by compiling a list of sites using Disqus that hosted unmoderated discussions featuring racial slurs or threats. They expanded to researching the ties between purported hate groups and any tech providers and shared their findings with Fast Company, which we confirmed independently.

A Range Of Reactions

Independent of Ellis and Gibney, SPLC recently called out one of these companies, Cloudflare, for providing internet security and bandwidth optimization to at least 48 designated hate sites using servers based in European countries with laws against Holocaust denial or the promotion or incitement of racial hatred. Perhaps the most notorious Cloudflare client is the white nationalist forum Stormfront, run by Don Black—a prominent, longtime leader within the Alabama Ku Klux Klan. A 2014 SPLC report by Beirich tallied nearly 100 bias-related murders committed by frequent posters to Stormfront, including Anders Behring Breivik, who killed 77 people in Norway in 2011. Correlation is not causation, but even Black seemed troubled by the events. “This makes me want to pull the plug on this place and never look back. We attract too many sociopaths,” he wrote in a forum discussion about the Breivik killings.

Cloudflare maintains that it’s a conduit for its clients’ content, which is hosted with other services and would be online whether or not Cloudflare were involved. (Using Cloudflare obscures the name of the actual host with online lookup services like WHOIS.)

Beirich disagrees. “Their description is bullshit, basically,” she says, “because whatever they say, they have got to put that material on a server somewhere so an Italian, for instance, can access Stormfront quickly.” She’s referring to caching copies of a site’s content in different locations so it’s closer to visitors. The company’s terms of service state that, “Cloudflare is a pass-through network and, at most, caches content for a limited period in order to improve network performance.”

Cloudflare says its focus is on the technical services that it provides to clients. “We’re not as involved with the content, and we also think we don’t necessarily have expertise to address those issues,” says Doug Kramer, Cloudflare’s general counsel. “Our approach is generally to not get involved in such things.”

One important exception is child pornography, he says, because the U.S. has strict federal laws against distributing such content. Kramer says that Cloudflare immediately sends any reports of child pornography on its network to federal officials. He says that Cloudflare also complies with law enforcement on other issues of illegal content or activities by clients. “We have a relationship with law enforcement where if they go through the steps, the due-process steps to come up with an order, we will adhere to that order,” says Kramer.

He says that Cloudflare doesn’t have the resources to go beyond the legal requirements and rattles off stats. The company has 425 employees to service 6 million websites. It handles 10% of global internet requests, amounting to almost 5 million per second. “You see increasingly people want to take tech companies and throw a lot of these difficult questions onto them,” says Kramer.

A recent article by ProPublica alleged something more dangerous than a hands-off approach. Cloudflare was forwarding complaints about abusive content to site owners, including the name and contact information of the person lodging the complaint. Such info, sent to The Daily Stormer (considered a neo-Nazi group by SPLC), led to vicious online harassment, several people reported to ProPublica. “It’s a very distasteful thing when that happens,” says Kramer. After the ProPublica report, Cloudfare revised its policies to allow fully anonymous reporting of threats and child sexual abuse material.

Cloudflare represents the far laissez-faire end of responses to handling unsavory or offensive content: Just keep the internet working, legally. “I can understand that Cloudflare is a moral absolutist, a free-speech absolutist, and I can appreciate that position,” says John Ellis. “They’re not violating their terms [of service] on hate speech because they don’t have terms on hate speech.”

The WordPress platform, owned by a company called Automattic, also has no such terms for the sites it hosts. “Our service allows anyone on the web to express their ideas and opinions, whether we agree with them or not—we don’t censor, moderate, or endorse the content of any site we host,” reads the company’s Freedom of Speech statement. Sites it hosts include American Vanguard (“We are White, we are nationalists, and we are Fascists.”), United Dixie White Knights of the KKK, and the American branch of Greek Nationalist group Golden Dawn, which critics consider to be a neo-Nazi organization.

Other companies that provide the pipes of the internet also tend to take a hands-off approach. “As stalwart supporters of the Constitution’s First Amendment, we believe that hosting providers should not be in the business of dictating acceptable content among its users,” writes Brett Dunst, a spokesman for DreamHost, home to sites including the American Nazi Party. Illegal activity is the one exception to the company’s hands-off approach, he says.

Google-owned Blogger is a tad stricter than most site hosts. We informed Blogger of eight controversial sites that it may have been hosting. It shut down one, the anti-immigrant Treasure Valley Refugee Watch. Three other sites, including Holocaust-denying The Realist Report, received what Blogger calls interstitials—pages that pop up and warn the visitor that the content may be objectionable.

Guilt By Association

On the other end of the spectrum, ad companies that handle automated placement on websites are sometimes the most aggressive about breaking ties with controversial destinations. That’s in part because such sites aren’t good places for its clients to be seen, says Josh Zeitz, a spokesman for AppNexus. But AppNexus also blacklists sites for moral reasons. “Our CEO is a donor to SPLC. He trusts them implicitly,” says Zeitz.

Judgments can be tricky, though. Satish Polisetti, CEO of Polymorph (formerly AdsNative), writes in an email that, “we have been internally wrestling with how to address the challenge of publishers that fall into the gray area of free speech that is considered offensive to many, but that does not necessarily cross that bright line into being hate speech.” Both companies audit all sites before they are eligible to use its network, and presence of hate speech is one of the criteria they may use to reject sites.

Ad company Rocket Fuel has a list of about two dozen types of content that can disqualify a site, and hate speech is one of them, says chief privacy officer Ari Levenfeld. One of its tools is a scanning service provided by Peer39, which not only looks for keywords but also evaluates the context of language on sites. It’s easy, for instance, to disparage racial groups without using actual slur words, but instead using fudged spellings.

We inquired about six sites tied to SPLC hate groups that appeared to use Rocket Fuel for advertising, including Radix Journal and American Renaissance, which also argues the genetic and intellectual superiority of white people. Ellis, Gibney, and their team used a browser extension called Ghostery to scan sites for advertiser tracking code, but any site owner can install the code on their own, even if they don’t have a business relationship with an advertising company. All six sites with Rocket Fuel code were already on the company’s global block list, said Levenfeld.

The activists flagged 67 hate group sites as possibly delivering ads from one or both of Google’s networks, AdSense and DoubleClick. When we sent the list to Google, it said that only 10 of them were actually running Google ads. It declined to discuss specific sites, but based on some numbers it did provide, Google appears to have dropped advertising from most or all of the 10 sites, as well as proactively blacklisting some sites that weren’t even running Google ads.

Google approves only 12% of the site publishers that apply to its network, the company told us. Its restrictive content guidelines prohibit even sites that sell alcohol or tobacco products. They also ban content that “incites hatred against, promotes discrimination of, or disparages an individual or group on the basis of their race or ethnic origin, religion, disability, age, nationality, veteran status, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, or other characteristic that is associated with systemic discrimination or marginalization.”

But the search giant’s strict policies have not absolved it: It’s been under increased pressure since reports by the Times of London about ads from major corporations, charities, and U.K. government agencies appearing alongside YouTube videos promoting extremist content. Google announced in late March that it will use better machine-learning AI to keep ads off content deemed too offensive and that it will give advertisers more fine-grained control over the kind of material they appear on.

The Messy Middle

The biggest controversy is for tech companies that fall in the middle of the range on content: They may have policies against things like hate speech or abusive comments, but are accused of not enforcing them. “These same companies that promote these values about liberty and being pro-immigrant, that are pro-gay rights, that are supportive of women’s issues, they’re taking money from hate groups,” says Ellis.

Often the wording of policies is vague or complex. Disqus’s terms of service, for instance, prohibit users from posting content that “may create a risk of harm, loss, physical or mental injury, emotional distress, death, disability, disfigurement, or physical or mental illness to you, to any other person, or to any animal.” That could be almost anything.

The terms say that Disqus may remove offending content, but that it “takes no responsibility and assumes no liability for any User Content that you or any other User or third party posts or sends over the Service.” Basically, it’s up to the site moderators, and of the 10 kinds of content they are prohibited from allowing, only one—”Intimidation of users of the Disqus Service”—appears as if it might apply to hate speech.

In response to mounting criticism, Disqus recently announced some new tools to fight what it calls “toxic comments,” such as the ability for users to report violations directly to Disqus if the site moderator doesn’t take action. It also promises to start using AI to flag (though not automatically remove) hate speech, but it hasn’t said when that will begin. “These seem like useful changes that will help them manage the hate issue across the platform,” says Ellis. “But at some point they need to make a clear stand about their values. When will they do that?”

Disqus does not host comments on perhaps the most virulent site: Stormfront. That falls to vBulletin, which also provides forum software for the neo-Nazi National Socialist Movement. VBulletin offers both a cloud service, which it hosts, and software that sites can run on their own servers. VBulletin, a division of California-based Internet Brands, did not respond to repeated requests to comment for this story.

The most widely used discussion platform is one you probably use yourself: Facebook. The social network’s comments plugin powers the discussions on several sites on the SPLC list, including Stop Islamization of the World, which advocates burning Qurans. Facebook has a policy of removing hate speech content, which it defines as attacking people based on numerous categories like race and gender. Facebook told us it will also remove a group that is “dedicated” to promoting hatred against those categories.

But it’s up to users to flag this content, so we did—sending Facebook a list of 18 sites that use Facebook pages or groups or its commenting service. The list includes black supremacist groups such as the Israelite Church of God in Jesus Christ and the Brooklyn-based All Eyes On Egipt Bookstore. The latter is connected to the Nuwaubian Nation Of Moors, whose founder, Dwight York (currently serving 135 years in prison for racketeering and child molestation), has made proclamations such as “White people are the devil.”

Facebook reviewed the list and dropped two groups: neo-Nazi Atomwaffen Division and Invictus Books, which sells anti-Semitic and pro-Nazi products. The groups that the SPLC labeled as black supremacist were not among those Facebook considers dedicated to promoting hatred.

Turning Off The Money Faucet

As the downfall of Bill O’Reilly shows, advertising boycotts can be powerful tools for activists. But advertising isn’t a big source of revenue for most SPLC-designated sites. Instead, they often rely on donations and e-commerce. PayPal is a player in both categories, providing services to sites including the National Policy Institute, American Vanguard, and Occidental Dissent, among others.

PayPal has a team dedicated to “brand risk management” that consults with outside groups to help find problematic customers, the company told us, though it would not name those partner groups. It said that several sites from our list were under review for violating its brief Acceptable Use Policy, which includes prohibition of “the promotion of hate, violence [or] racial intolerance.” The company sent us a prepared statement that read in part, “PayPal’s policy is not to allow our services to be used to accept payments or donations to organizations for activities that promote hate, violence, or racial intolerance.”

Other fundraising platforms strive to remain neutral. Despite his personal distaste for Spencer’s views, Zhang says he reluctantly chose to continue providing service to Radix Journal and NPI, citing a recent legal ruling that allowed Spencer to speak at a rented auditorium at Auburn University in Alabama because the judge determined that Spencer doesn’t promote violence.

However, when Radix and NPI switched to Memberful (without informing Donorbox why), Zhang said, “Good riddance. We are happy that they are no longer using us.” Zhang says that Donorbox has dropped some customers it deemed were harassing or threatening, including Holocaust denial site The Realist Report.

Memberful falls farther on the laissez-faire end of the range. The tiny, three-person company says it wants to be a neutral service provider. Both Memberful and Donorbox are platforms that sit on top of payment’s processor Stripe, which in turn sits on top of banks and credit card companies such as Visa and MasterCard. Stripe follows the guidelines of those payment systems, such as banning online get-rich-quick schemes or shady purchase arrangements that could be used for money laundering. Beyond such requirements, Stripe doesn’t have any policies around the content of sites. Stripe would not comment for this article.

Some of the most blatant sites were already shut out of the online payments system. The American Nazi Party and Holocaust denier Carolyn Yeager, for instance, take cash or money orders. The Daily Stormer takes cash or Bitcoin.

In addition to hosting sites, Squarespace also provides e-commerce or fundraising support to some of them, such as Radix Journal, and the National Policy Institute. In contrast to the “no comment” from Squarespace, we got a quick reply from CafePress, which provided online stores to Stop the Islamization of the World, VDARE, and Yahushua Dual Seed Christian Identity Ministry, which claims that “Many of the people we call Jews today are indeed descendants of Satan…”

CafePress dropped the three sites within about a day of our contacting them. The company says that it uses SPLC as one of its resources to evaluate clients (though obviously some slipped by). It has extensive guidelines, such as prohibiting hateful or racist terms or symbols.

“Once we become aware that a recognized hate group is using CafePress to sell merchandise, we remove the images and shut down their shops immediately,” writes spokeswoman Jessica Lutchen in an email.

Another large online store provider, Shopify, takes a stridently free-expression stance. It services three SPLC hate sites, including Generations, whose director, Kevin Swanson, supports Uganda’s legal crackdown on gays, which includes the death penalty. Swanson often reminds his audiences that the penalty for homosexuality is death and seems to flirt with the idea that it should be enforced if people refuse to repent. Shopify, which has also taken heat from activists for powering the stores of Breitbart and its former tech editor Milo Yiannopoulos, declined to comment for this article.

A Hard Battle To Sit Out

The two ends of the spectrum are the easiest to understand. CafePress is especially strict: It provides a long list of verboten content, and claims the right to drop clients for yet more things not on the list. Cloudflare is especially lenient. It allows any content that isn’t illegal; and with the exception of child porn, Cloudflare leaves it to law enforcement to make the call. Both types of policies will have fans and detractors, but both are consistent and easy to grasp.

Life isn’t usually that simple. Disagreement is inherent in discussion forums on services like Disqus and Facebook. The filter bubble effect—hearing only from people who share your views—has possibly led to more division and extremism in the United States and other countries. A variety of views can challenge and break down prejudices, or expose them as intellectually bankrupt—in theory. But at some point, we have to ask if views go too far for a community to tolerate, or for a moneymaking enterprise to take the risk of handling.

Working to strike a balance between free expression and extreme prejudice is a messy struggle. But it’s a worthy one, says EFF’s Sophia Cope, lest we risk going too far in either direction. “If we have very aggressive companies that are making all of these content decisions … and acting in a very over-broad way, then it will be true that whole categories of speech and whole categories of people will be prevented from sharing their ideas in the marketplace of ideas that we value as a country,” she says.

Commerce isn’t exempt from controversy. Bill O’Reilly isn’t the first pundit brought down by an ad boycott, and his high-profile downfall will almost certainly embolden activists to use the tactic on other foes. Companies may argue that they don’t have the expertise or resources to take a stand on issues outside their main business areas. But in an increasingly polarized and angry world, there’s less and less appreciation for neutrality.

(164)