Are Investors Still Squeamish About Putting Money Into Women’s Health?

Karen Long is no stranger to entrepreneurship, having worked at fast-growing startups in everything from biotech to wine. But with her newest company, Nuelle, she faced some hurdles that she’s never encountered before.

Nuelle is a device that is designed to encourage arousal for women who experience problems with their sex drive at various stages in their lives. Long says she started the company after conducting extensive user research, in which many women shared that they lacked alternatives to hormone therapies.

“This was where we saw one of the greatest unmet needs in health care,” says Long, who saw an opportunity to create a device-based alternative. After assembling an all-female executive team that included obstetrician Leah Millheiser and former Art.com senior vice president of marketing Lesa Musatto, she set forth for Sand Hill Road to secure the company’s first big check.

Long expected that it would take some time to find the right set of backers, but she didn’t anticipate her all-female team being referred to by a male partner as “the Charlie’s Angels.” Nor did she expect that she’d face the kind of blatant dismissals that she did: She was regularly laughed at in pitch meetings, and was told by several venture capitalists that she must be exaggerating the data, as “it doesn’t happen to my wife.”

Long did succeed in raising capital from New Enterprise Associates (NEA) and Correlation Ventures, and is readying for her next round after releasing the first product. NEA’s health investor Josh Makower noted in a recent interview that the fundraising process for Nuelle was a unique and challenging feat, despite the extent of the problem and the market size.

Fortunately for Long and other founders, some reports are finding a rise in institutional investment in women’s and children’s health. Seed fund Rock Health looked specifically at digital health startups and noted a steady increase since 2011. Five years ago, when the firm started recording data, no companies in this category raised more than $2 million. By the third quarter of 2015, nine companies had already raised $84 million. The same report found that about a quarter of women’s health companies that raise venture capital have female CEOs, which might seem low, but it is higher than the 7% average for health-tech startups.

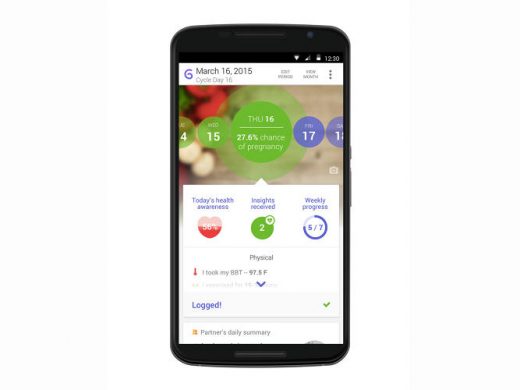

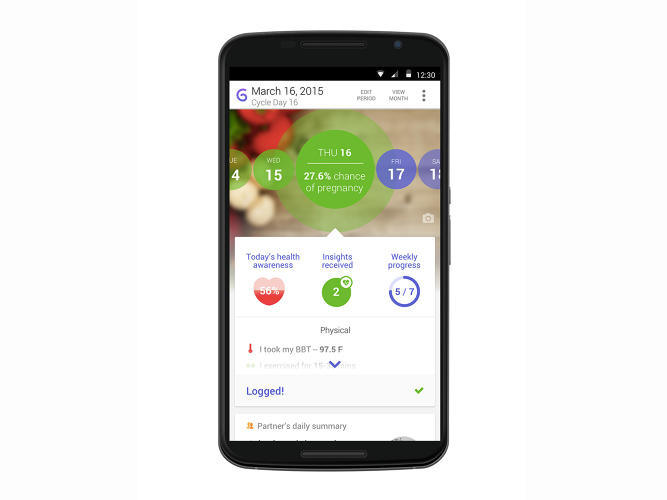

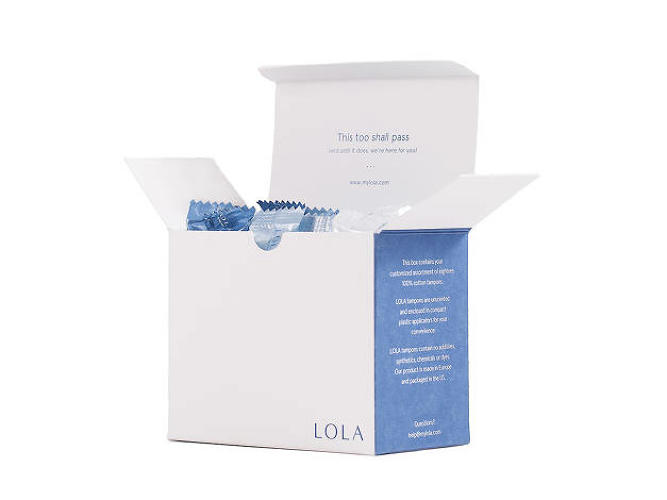

But as with any space, some categories are trendier than others from an investment standpoint. Fertility and reproductive health is gaining traction. Women get their period monthly for decades, which puts it in a different category to pregnancy-related products that are only used for a small window of time. Some examples are Glow, a fertility tracking app (incidentally, started by six men); Thinx, maker of period-proof undies; Lola, a tampon delivery service; and Looncup from Loonlabs, a smart menstrual cup.

In light of this trend, some who follow the space say that women’s health is no more challenging than any other area of health technology. “From what I am seeing, fundraising in general is hard, and even harder in the health care landscape,” says Carla Brenner, founder of Health Tech Women. “I would not single out women’s health.”

“Finer Points Of Problems”

But in interviews with Fast Company, many founders of women’s health companies shared harrowing stories that highlighted ongoing cultural resistance from the venture capital community.

Some, like venture capitalist Tammi Jantzen, have chalked it up to the lack of female investors. Recent studies have found that about 7% of venture capitalists at the top 100 firms are women. As Jantzen noted in a recent op-ed, some of the “finer points of problems,” such as childbirth injuries, women’s sexual health, symptoms of menopause, and even early childhood health have largely been missed by the mostly male venture capital community.

Julia Cheek, founder of an at-home testing company for women called Everly Well, says that conversations with male investors took a turn for the awkward when she shared plans for a breast milk nutrient test. Cheek believes that this makes it inherently harder to win funding. “There are just fewer investors who have industry expertise or are actual consumers of the product,” she says.

Even male entrepreneurs of women’s health companies shared similar tales. When fundraising for his pregnancy wearables startup, Bloom Technologies, Eric Dy says he heard some investors dismiss the space altogether because they’re “not familiar enough with it.”

At one point, Dy considered passing on the baton to a female CEO who might make a more compelling case. But he was cautioned against it, as investors told him they had seen female executives of similar companies get rejected on the basis that it’s “just their own personal experience.” Lesser entrepreneurs would have given up, he says, but the turning point came after his team received a startup award from Richard Branson. It also helped to start personalizing the narrative as much as possible to highlight the physical and emotional toll of pregnancy complications for families. “You have to find ways to get them emotionally invested,” he says.

A “Niche” Market

Despite the fact that women account for half the population, many of the founders I spoke with say they also heard that their product is too “niche” to generate a sizable return.

That might be legitimately the case with some startups, but other investors feel that it’s unfair to paint the category with a broad brush. Bessemer Venture Partners’ Steve Kraus has heard that criticism before, despite that “his most successful deal ever” was in women’s health: a now-public fertility company called OvaScience. “It’s hard for some male investors to understand women’s health issues,” he says. “To say that it’s not a big enough market is ludicrous.”

But it’s not all doom and gloom for budding women’s health entrepreneurs. Long says she’ll frequently get together with other founders to share best practices and war stories. These support networks are increasingly vital to her company’s growth. “I haven’t felt much competition from other women’s health companies,” she says. “We know that we all have a better shot if we help each other.”

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(37)