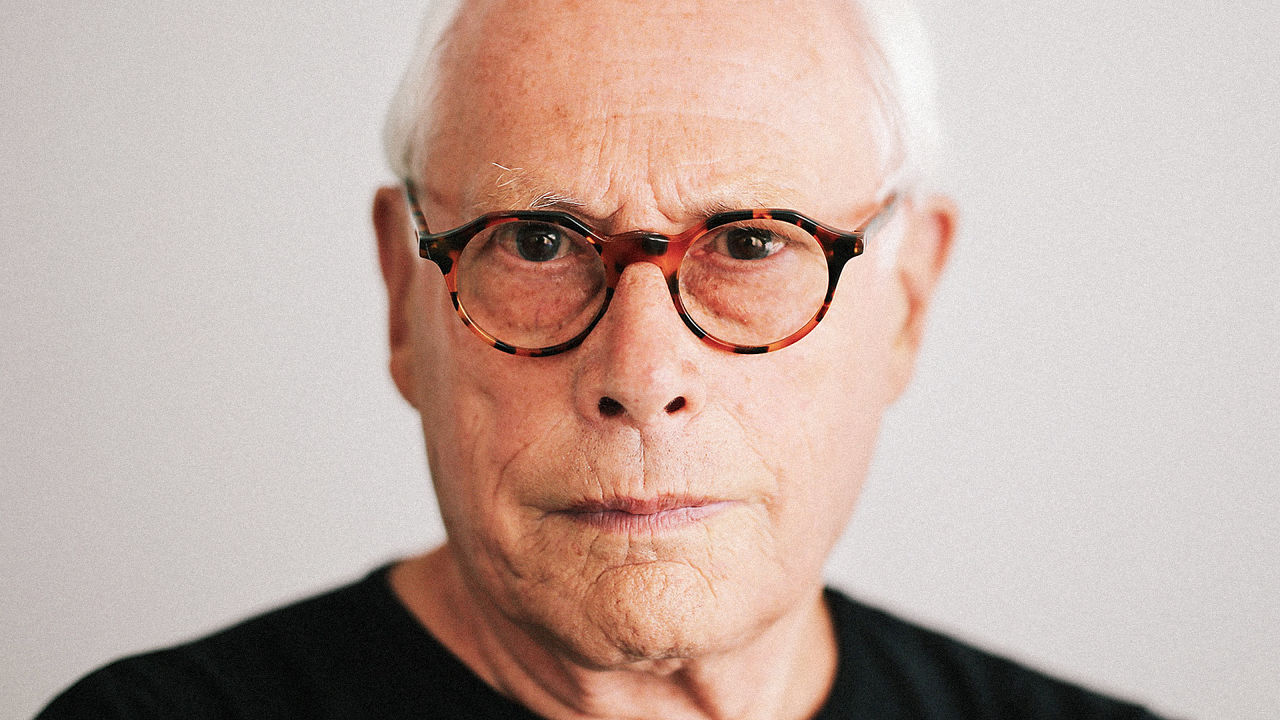

Dieter Rams Is Finally Getting The Feature Film He Deserves

Gary Hustwit isn’t done making films about design just yet. The documentary filmmaker behind Helvetica, Objectified, and Urbanized—the trilogy that helped popularize design in the U.S.—is back with a documentary about legendary German industrial designer Dieter Rams.

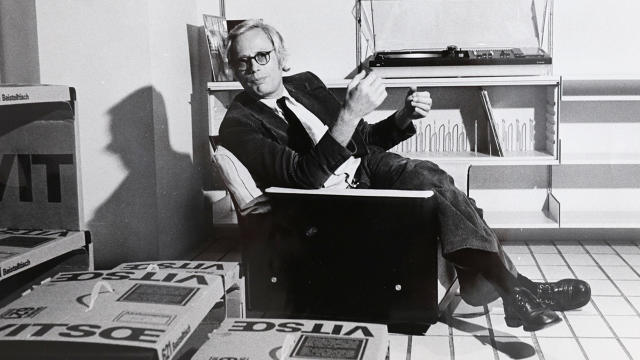

“I couldn’t believe there wasn’t already a great documentary about him,” Hustwit says. Rams, now 84, is widely revered for his sleek, functional products for manufacturers Braun and Vitsœ, as well as his “Ten Principles of Good Design.” His influence can be felt in everything from Apple products to user interface design. He’s also famously private—Hustwit’s Rams will be the first feature film on the designer.

Hustwit met Rams while interviewing him for Objectified, his 2009 documentary about the masters of product design, but didn’t begin to pursue the idea of a lengthier interview until early last year. He met with Mark Adams, owner of Vitsœ, who suggested Hustwit might have the best shot at a documentary on Rams since he was pleased with his interview in Objectified. After several conversations with Hustwit about the film, Rams ultimately agreed. “He still wants to pass his philosophy and ideas down to the next generation,” Hustwit says. “When I was talking to him about the film, that’s the only way that I could get him to do it.”

Hustwit flew out to Rams’s home in Kronberg, Germany, just outside of Frankfurt, where he lives with his wife, Ingeborg, among a living archive of his famous designs from the ’60s and ’70s. After two weeks of filming, Hustwit is launching a Kickstarter for the film. The funds raised will help him finish the film, which Hustwit says will include interviews with people close to Rams to put his work into context (he is not yet disclosing those names). The money will also be used to help preserve, digitize, and catalog the archives of the nearly 500 products Rams designed or oversaw the design of. Those archives are split between his home and the MAK museum in Frankfurt.

We sat down with Hustwit to talk about Rams’s childhood, his views on industrial design today, and what he would have been if not a product designer.

Co.Design: Do you remember when you first became familiar with Dieter Rams’s work?

Gary Hustwit: Growing up, my dad had a Braun shaver and we had the orange juicer, and I had an alarm clock at some point. Growing up in Southern California, somehow I was surrounded by products that were designed by this German designer. At the time, of course, I didn’t realize that. They were just these objects in my life. It was only later that I started getting interested in design that I realized so much of it was coming from this one man. I was surrounded by Dieter Rams even though I didn’t know it.

What did you learn about Rams over the course of these interviews that you didn’t know before?

He’s never done an interview this in-depth before. We did two weeks of conversations, and it was important for me that we do the interviews in German. Rams’s English is good, but anytime I’m interviewing a designer, I want it to be in their native language so they are really able to express themselves. My German is not good/nonexistent, so for one week I had [type designer] Erik Spiekermann as my German avatar. He basically facilitated the conversations, and I was present as well. For the second batch of the conversations, Sophie Lovell, who did the Rams’s book As Little Design As Possible, helped out as well.

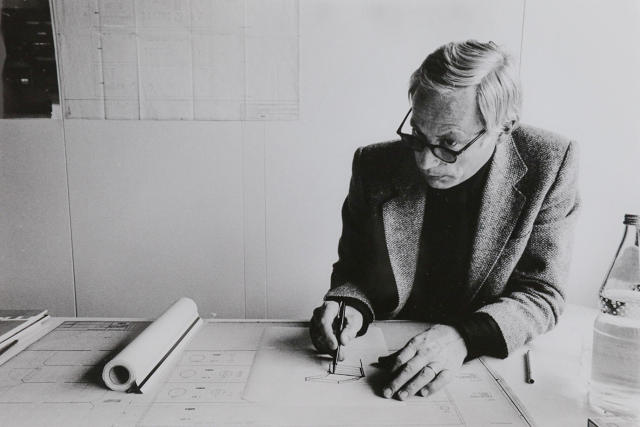

The things that fascinated me were just the details about growing up in World War II-era Germany. The scarcity and having to really be as creative as possible. We went back to Wiesbaden to his childhood home and went to all the places he spent a lot of time in as a child.

There was one thing—this is the kind of detail that only comes out of a long interview—but I was trying to pinpoint his early inspiration, why he got involved in design, and what piqued his interest. He remembered this tram that goes up a mountain outside of Wiesbaden. It’s water-powered, and it’s really a fascinating piece of engineering. Basically there’s a water tank at the top that fills up a tank under the tram and that pulls it down the mountain. As it’s doing that it slings up the upbound train. Then when it gets to the bottom it dumps out the water. He was fascinated and spent hours watching the workings of this tram as a child. It was one of those moments where he got fascinated with the way things work.

Was there anything that Rams wanted to design or do with his career that he didn’t do? Any passion project unfulfilled?

One of the reasons that his story is fascinating to me is that he’s this renowned designer that has seen the design of 500 products, but he looks back at his career and says if he had to do it again he wouldn’t want to be a designer. He thinks that the work he’s done has contributed to this commercialized, consumerized society. That there’s so much unnecessary stuff in the world, and he feels like he’s been a part of that.

Even since the ‘70s, he’s been talking about sustainability and environmental awareness, but I think he looks around now at the world of industrial design and product design and feels disgusted by most of it. And feels that he had some role in it. He trained as an architect, and I think that if he could do it over again he would be an urban planner. That’s what he still wants to be, he still talks about it. He’s fascinated by cities and wanted to be involved in that. But the way his career path went, he went to Braun and the rest is history.

What is his day-to-day life like now?

He’s retired but he’s still involved in the design and redesign of his products from Vitsœ. He still speaks. He just got back from a trip to Japan where he spoke to some students there. He swims in his pool, and he takes care of his bonsai trees.

He still wants to pass his philosophy and ideas down to the next generation. When I was talking to him about the film, that’s the only way that I could get him to do it. He feels like he’s told some of these stories so many times, but I like to think I got him to go beyond that in our conversations. But that idea of passing on what he learned, both about design but also about consumer culture, is what motivates him to do a film like this.

What is his impression of the field of industrial design today?

He’s still very, very critical of today’s designers. He’s just kind of unhappy overall with the state of the overabundance of junk out there. He wishes that people would change their relationship to what they buy and be more considerate of what they use and what they use it for.

What was it like being in his house? Any collections or hobbies you wouldn’t expect?

He has all sorts of collections. He has all of these things his grandfather gave to him, all these measuring instruments and tools. His grandfather was a huge influence on his life. He was pretty much raised by his grandparents. His grandfather was a carpenter and Rams, early in his childhood, was learning from him. Those are the things he treasures most.

He also has a ton of Japanese objects. He’s always been obsessed with Japanese culture and design. Tea cups and letter openers and all kinds of things. His house is like you’re living inside a Dieter Rams design. Everything is either work that he’s designed or inspired him or was given to him by other designers or artists.

Is he as systematic and perfect as you would expect based on his design philosophy?

Yes, definitely [laughs]. He and his wife live it every day.

It’s almost the same thing I experienced going to Massimo Vignelli and Lella Vignelli’s house. Everything you see and everything that they are using is designed by them. The coffee cups and the chairs you’re sitting in and the clothes that Vignelli was wearing. It’s that modernist ideal of designing your world. Rams is in that same mindset.

Was there one object that resonates with you personally?

There’s so much. When you’re in his house, it’s like you’re in a museum because he has multiple examples of everything he’s designed somewhere in the house. So it’s incredible to see these objects he designed in the ‘60s and ‘70s still in their original boxes.

There were several things that I didn’t realize he designed. When Gillette bought Braun, Rams and his team started doing a lot of design for Gillette. I didn’t realize that Rams designed one of the original Oral-B toothbrushes and probably one of the ones that I had used as a kid. It was just interesting to see how far one man’s influence stretches. How these objects end up being a part of our lives. We don’t realize we have this relationship with this German guy through all the stuff that we use everyday or grew up with.

The Kickstarter for Rams launches today. You can find it here.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(18)