For Banking App Monese, Founded To Serve Migrants, Brexit Has Been Good For Business

Serial entrepreneur Norris Koppel, an Estonian by birth, understands all too well the challenges faced by immigrants. When he moved to the United Kingdom 17 years ago, he was denied a bank account because he didn’t have a British credit history or utility bills. Unable to get paid and unable to rent an apartment, it was “humiliating,” says Koppel. In 2013, after selling a successful fintech startup, he resolved to make banking better for the U.K.’s 3.5 million migrants—and ultimately for the 247 million migrants worldwide.

It’s a noble mission, but also one with real economic benefits. Better integrating migrants into society, according to a McKinsey & Company report, could generate an additional $1 trillion annually on top of the $3 trillion global GDP boost that they already provide by working in places of greater opportunity.

Now, with Brexit negotiations underway, it’s unclear whether the U.K. will reap the benefits of migration going forward. But for Monese, the mobile banking app that Koppel launched in 2015, Brexit has been all upside so far.

“Personally, none of the people in our company or fintech companies like Brexit,” he says. “Monese is all about breaking down the walls, making it easy to include people. But as it happens, [Brexit] has been immensely good for us as a business.”

Since the referendum vote on June 23, Monese’s customer acquisition costs have been “way down,” according to Koppel, thanks to a leap in word-of-mouth marketing (customer acquisition, by the end of 2016, was 90% organic). Plus, U.K. newcomers are taking advantage of the European Union’s open borders while they can. “There is a huge surge in migration at the moment.” So far, 85% of Monese’s 40,000 users are migrants and 15% are underbanked citizens. Before Brexit, the company had 20,000 users.

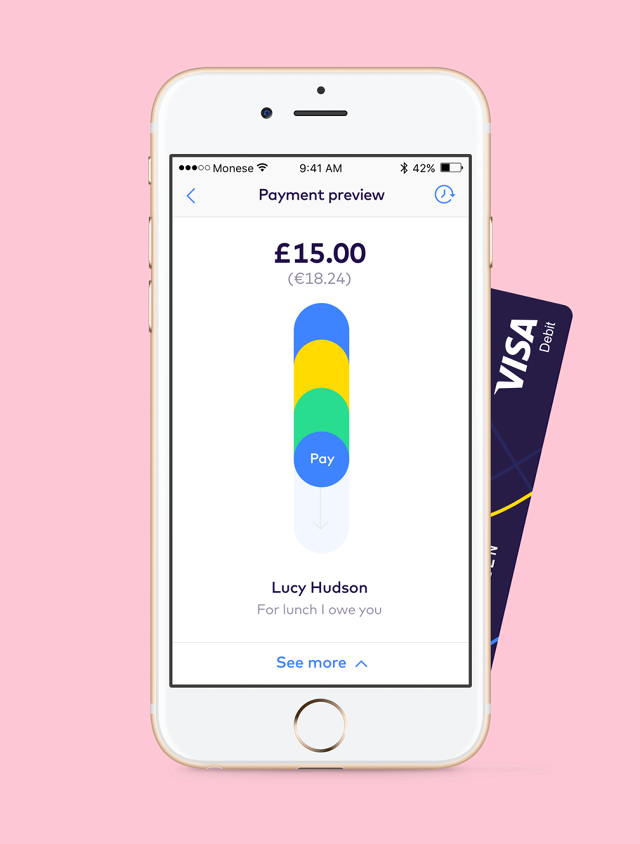

To open a Monese account, users snap a picture of their ID and take a selfie. In the background, Monese runs an identity check using data from the user’s country of origin. Once up and running, Monese mirrors the functionality of a standard checking account, with cash and direct deposit; a Visa debit card; and ATM withdrawal functionality. The app also includes features designed for migrant populations, such as global payment processing.

Since launching, Monese’s biggest change has been to its business model. In the early days, the company planned to charge by transaction—but customers revolted. “Designed to be fair, the perception about it was the opposite,” Koppel explains.

Today, Monese charges a flat fee of £4.95 per month, plus a wholesale rate of 0.5% for currency exchange. “We’re not going to be breaking even with every customer,” Koppel acknowledges, “but it’s super simple to understand.” If the average Monese customer banked with Barclays, Koppel says, he would end up paying five times the amount for the same services.

“The pain is so huge, people are desperately Googling to find a solution to the problem. You need a bank account to exist, to buy food,” Koppel says. With the $10 million in Series A funding that Monese announced last week, he plans to make a bigger push to acquire customers in Europe. “This has always been the goal, to become not just pan-European but a global bank, accessible wherever you go.” Existing users will be able to open an account in a European country with just one tap.

Despite a growing emphasis on markets outside of the U.K., Koppel does not plan to relocate his London-based team, which conducts compliance and marketing (customer service and engineering are in Estonia). Larger banks are considering moves to financial centers on the continent, but startups, by and large, have shown little interest. “We haven’t had anyone in our community talk about leaving,” even if a hard Brexit scenario were implemented, says Lawrence Wintermeyer, CEO of Innovate Finance, an advocacy group representing over 200 U.K. fintech companies. “More than likely, what you would do is relicense your operation in Dublin or Brussels or Frankfurt.”

Wintermeyer’s primary concerns for his member companies revolve around financing and talent. “The most important thing is, let’s not do anything that detracts investors from coming to the U.K., let’s be sure we remain attractive,” he says. Plus, “we want to be sure we have access to talent.”

As for companies like Monese: “Financial inclusion is a broad and important trend to pay attention to,” Wintermeyer says. “It’s where digital has a really big role to play, but you’re going to need volume.” Many fintech startups find themselves gravitating toward the wealthy in order to achieve scale because customer growth in financial services is so slow.

Despite the obstacles, an increasing number of fintech founders are setting their sights on serving less affluent populations. In Egypt, for example, there is Dopay, a cloud-based payroll product for unbanked employees. In the U.S., there are more established players like Oportun, a credit provider for underbanked Hispanic families, and young entrants like Bee, a mobile-only banking app that has grown by canvassing neighborhoods like New York’s South Bronx.

The typical Bee customer has less than $1,000 in liquid assets or makes less than $50,000 per year, says founder and CEO Vinay Patel. “Most banking products are fundamentally not built for mobile-only use. They’re built for mobile as a secondary channel,” he says. Checking accounts are Bee’s point of entry. “You need to get paid without it being slow, inconvenient, and expensive.”

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(49)