Frank Ocean, Apple Music, And The Headache Of Streaming Exclusives

This weekend, I had a brief, uniquely modern conversation with somebody as we both stared into our phones together.

“The new Frank Ocean is out.”

“Oh damn, really? Let me pull it up.”

“It’s only on Apple Music.”

“No, look, here it is on YouTube.”

*Pitch-shifted audio of Frank Ocean singing like a chipmunk*

“Oh. Weird. I guess I should sign up for Apple Music.”

“Yeah, there’s a free trial. Or you could just torrent it.”

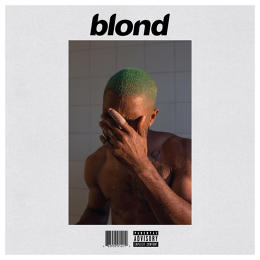

For those of us who follow technology news and the constantly evolving music industry, the exclusive arrival of Ocean’s Blonde on Apple Music on Saturday came as no surprise. After Rihanna’s Anti, Beyonce’s Lemonade, Kanye West’s Life of Pablo, and Chance the Rapper’s Coloring Book, we’ve come to expect big names to drop new albums with restrictions: This one’s only on Tidal. That one’s only on Apple Music. Want to buy the album in a record store? Fat chance. This is 2016. If you’re lucky, there might be a pop-up shop, though.

This year’s string of high profile, platform-exclusive online album releases is beginning to condition everyday consumers to this new reality, but for many, the concept remains confusing, if not frustrating. You mean I have to sign up for a $10 per month subscription just to hear this new album? Why? This is a bit like telling N’Sync fans in 2002: Sorry kids, this one is only available at Tower Records. You might live near a Best Buy or prefer Sam Goody, but it doesn’t matter. For now, this music you and millions of others have been waiting for is a Tower Records exclusive.

“Why?” is a valid question. After all, the big-name artist streaming exclusive is a new feature of the music economy that has cropped up as the relationship between artists and their fans is once again being renegotiated. Consumers have a right to wonder why their dollars are being lured in new directions, especially now that the internet has spoiled us into expecting to call the shots and, for better or worse, access our culture at little to no financial cost.

Fortunately, the question has an answer: You can only stream Frank Ocean’s new album on Apple Music (for now) because Apple said so. More to the point, it’s because the company has enough cash in its reserves—and deep music industry relationships, thanks to its absorption of the Beats Music leadership—to get early, exclusive rights to albums like Blonde and Chance The Rapper’s mixtape Coloring Book. It’s the same reason Tidal had the latest records from Kanye, Rihanna, and Beyonce before anybody else did. And even though major labels are reportedly having second thoughts about the platform exclusivity strategy, Blonde certainly won’t be the last one.

As streaming becomes the dominant way we listen to music and the competition in the subscription market heats up, these short-term exclusives are one of the few ways that music services can truly compete against one another. In effect, rich men are using access to culture as a competitive weapon against one another in the battle over the future of how the music business works.

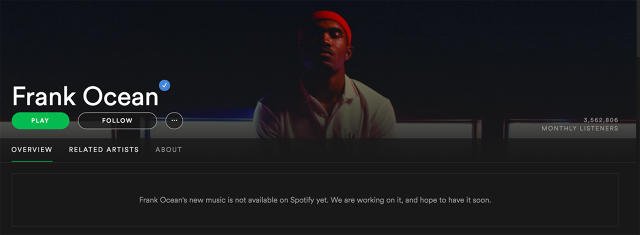

The exclusive access strategy is good for those wield the sword each time and bad for those standing at the other end of the blade. Imagine the anguish at Spotify, for instance, every time they see massive spikes in searches for “Frank Ocean,” “Kanye West,” or “Radiohead” and are forced to show listeners that painful blurb of copy in the UI: “Frank Ocean’s new music is not available on Spotify yet. We are working on it, and hope to have it soon.”

Exclusive releases are undoubtedly good for Apple. They tie the company’s brand to coveted works by beloved musicians and presumably lure many people to its new subscription service, helping (along with its three-month free trial) Apple Music amass 15 million users in just over a year. But if Apple succeeds in the streaming-music market with strategies like this—and by reportedly offering higher payouts to the major labels—it’s succeeding less by innovating and more by virtue of its size and willingness to throw its economic weight around.

For streaming companies, the pros and cons of exclusives are clear. But tech companies are hardly the only stakeholders here. What about artists? What about fans?

For musicians, the impact of exclusives is debatable. Chance the Rapper’s Coloring Book became the first record to chart on Billboard’s top ten based entirely on streams. But while the temporary exclusivity of Chance’s mixtape didn’t prevent it from charting, the question is begged: If it was also available to Spotify’s 100 million listeners for those first two weeks, could it have hit number one?

This question may be one reason that big labels are already rumored to be rethinking the exclusive release strategy altogether—but it’s also because of real-life scenarios like Universal apparently being snubbed by Ocean, who released the brief visual album Endless at the end very end of his label contract and then, days later, when his contract was expired, dropped Blonde on his own. In the long run, Ocean’s move may be seen as a liberating moment for artists eager for freedom from the tyranny of record labels. But for now, most artists still need labels for incubation and marketing muscle. And let’s not forget: Labels still own the rights to the expansive music catalogs the streaming services need to survive.

Former Apple employee Sean Glass argues that exclusives are good for artists because Apple invests heavily in them and even collaborates creatively on things like videos, often supporting artists in a way that labels are increasingly unable. Still, as Glass points out, the exclusive release approach overlooks indie labels and smaller artists. Such a strategy may well work out for massively popular artists deemed worthy of such partnerships, but the scheme—designed to drive hordes of people toward the streaming platform’s “subscribe” button—likely wouldn’t work with smaller artists. If there happens to be a trickle-down effect from blockbuster exclusive releases for middle class artists (more users on the platform mean more potential ears for smaller artists), it’s too early to tell.

So far, these exclusive deals are having at least one consistent effect: They’re sending people who don’t want to sign up for a second streaming subscription scurrying back to torrent sites, threatening to counteract the promise of streaming music to thwart piracy. For Kanye West, limiting Life of Pablo to Tidal (which has vastly fewer subscribers than Spotify or Apple Music) led to a surge in illegal downloads of the album. Unsurprisingly, Frank Ocean’s new album (along with the mini “visual album” that preceded it just days earlier) quickly found its way to file lockers, Reddit threads, Google Drive links and torrent sites as frenzied fans scrambled to finally hear it.

For fans, it’s nearly impossible to argue that the exclusivity wars have any benefit. It’s not like springing for both Hulu and Netflix, as DJ Skee argues in a recent op-ed, because unlike those video platforms, the overwhelming majority of the content on music services is exactly the same. If you pay $10 a month for Spotify but want all the latest releases from the likes of Drake and Rihanna as soon as they’re available, you’re looking at doubling (or potentially tripling) your monthly investment in music while only gaining a tiny fraction of additional content, however beloved much of it may be. For listeners, this equation makes no sense. And as the exclusivity war rages on, no single service is going to have a comprehensive offering of new music. Increasingly, new releases are fractured across services. And as the music industry knows all too well, a free torrent is still just a few clicks away.

This new reality differs from the one we were promised. Back in 2005, academics David Kusek and Gerd Leonhard envisioned an almost utopian world in which we would access “music like water,” essentially paying for access to music just like another monthly utility bill. At the time, their book, The Future of Music: Manifesto For The Digital Music Revolution, may have sounded radical, coming as it did two years before Spotify or even the iPhone. But indeed, the rise of streaming services has put tens of millions of songs into the pockets of listeners for a monthly fee. And while no streaming service will be completely comprehensive (SoundCloud and Bandcamp are excellent, essentially freemium ways to augment the libraries of Spotify, Tidal, and Apple Music with newer, more under-the-radar artists), fans have a reasonable expectation to be able to conveniently access new, popular music without jumping through hurdles or switching between services. The problem is that it’s one thing to sign up for Tidal because it offers the back catalogs of Prince and Neil Young. It’s another to regret the decision because Apple scored the exclusive rights to the next Drake album. It’s a bit like if one phone company let you call everyone except your best friend, while another let you call everyone except your mother. That’s not how utility companies work.

With Blonde, Frank Ocean fans are at least able to buy a download of the album for $9.99. But that’s little consolation to consumers who are weaning themselves off of downloads and know that for the same price, they can access millions of albums for a month. Or perhaps they’re already signed up for another service, gritting their teeth and wondering where the next hot new release will land.

Related Reading

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(21)