GM To Top Tech Talent: Ditch Silicon Valley For Detroit

When General Motors CEO Mary Barra first visited Cruise Automation, the autonomous systems startup GM acquired last spring for $581 million, she told its staffers, “I want to take your energy and speed, and your way of looking at things, and drive it into the core [of GM].”

That would be some feat for the Detroit automaker famous for one of the most dysfunctional bureaucracies in corporate history. But ever since taking the helm in January 2014, Barra has been on a crusade to radically change that culture.

Her urgency is understandable: GM’s business is about to change profoundly, thanks to the convergence of ride-hailing, car-sharing, electric propulsion and autonomous vehicles. GM is no longer only competing for talent with Ford and Chrysler. Now, it must face off with the likes of Uber, Lyft, Apple, Alphabet, nuTonomy, Mobileye, Tesla, Quanergy, and Didi Chuxing.

Top-Down Seismic Shifts

To give GM the kind of cultural fuel injection that would allow it to stand apart from the pack, Barra has launched a series of culture-shaking initiatives across the company, starting with herself and her own executive floor at GM headquarters, in Tower 300 of Detroit’s Renaissance Center.

Barra leads by example. She put herself front and center during GM’s ignition-switch crisis, when the company was implicated in over 150 fatalities. And it’s evident to anyone who’s spent time at the company that she’s forged close relationships with president Dan Amman and global product chief Mark Reuss, two contenders for the CEO job she got in January 2014.

According to GM’s HR chief John Quattrone, “Mary believes that if we change the behaviors on this floor, people who work for us will see that and emulate it.” Once a quarter, the top 16 executives in the company gather offsite for two full days. “All we do is focus on how we behave with each other,” says Quattrone. “I don’t want to get into a lot of detail. But we talk about conflict. How we manage conflict with each other. We talk about the things that someone does well, and the things that, ‘Hey, we think you can improve on.'”

For those just below this core group of 16, Barra launched a program called “Transformational Leadership.” Over the course of one year, a group of 35 executives spend a total of five weeks visiting customers in regions like South America and Asia, learning the principles of design thinking at Stanford’s d-school, and using what they’ve learned to come up with strategies GM can use to address “big, disruptive, strategic game changers,” says Michael Arena, a Wharton and MIT professor who now serves as GM’s chief talent officer. The company’s car-sharing initiative, called Maven, came directly out of the work of the first cohort in the program.

Culture Clubs

These behavior-changing efforts go all the way down to the rank-and-file. I recently sat in on the two-day summit of a grassroots initiative called GM 2020 that Michael Arena launched in 2014. He partnered with MTV Scratch, a Viacom consulting division that emerged from the music channel, and handpicked 30 millennials from different parts of the company who were tasked with energizing and disrupting GM’s culture.

“We quickly realized that we needed the middle of the organization as well,” Arena admits. “The millennials have great ideas, but middle managers can get stuff implemented,” he explains. “So we had the 30 reverse-invite any middle manager that they would want to play with on a challenge.” Once the initial 60 employees were assembled, Barra gave them one simple goal: Let’s make GM a place that everyone wants to work at by 2020 (hence the name).

In two years, GM 2020 has over 1,000 employees participating in a variety of ways. Some take “catalyst” classes, where they can learn design thinking. Others self-organize into small groups called co-labs, where they try to solve problems ranging from workplace concerns, to how car interiors should be redesigned to be more convenient for women with purses and a jumble of electronic devices. The program is built to ensure access to top brass. At quarterly get-togethers attended by senior execs, 2020 members describe the work of the co-labs and how they’re pushing their solutions through the GM hierarchy.

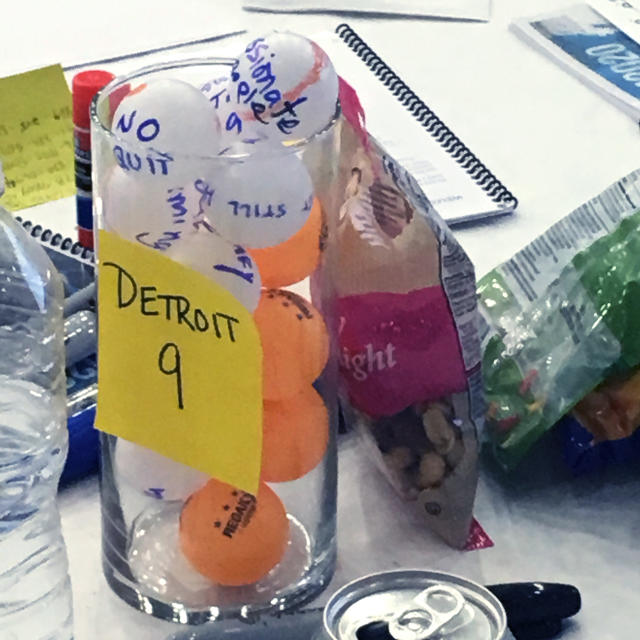

The day I visited, 250 people were seated at tables of eight in a large auditorium in Detroit’s Center for Creative Studies, a building that once housed the company’s design studio. Tables are covered with neon Sharpies, 2020 badges, snacks, and colorful notebooks. GMers filled a highball glass in the middle of each table with ping-pong balls. They scribbled such “wins” as “GM2020,” “millennials in the ‘D’ (D=Detroit),” and “the willingness to change” on the yellow balls. “Opportunities” such as “negative media,” “difficult to make changes,” and “multitasking in meetings” were written on the white ones.

The room is pretty quiet as everyone pays attention to the group up on the makeshift stage. They’re performing an impromptu skit designed to show off one of the seven “behaviors” Barra and others want to drive through the organization. The entire collection: Think Big; Start Small; Scale Fast; Listen Intently; Ask Why; Find a Friend; Follow the Energy; Lean into Conflict; Be Bold, as well as the ping-pong balls are things you’d more typically associate with a startup. While they’re antithetical to the old GM culture, they weren’t actually borrowed from Lyft, Cruise, or any other place. GM had all of this before the acquisition and investment—ever since Barra took the helm.

When the skit ends, a bouncy moderator wearing a blue 2020 T-shirt asks for comments from the crowd. She gets lighthearted theatrical reviews, as well as a few comments connecting the skit to a variety of workplace issues, like the parking problem at the Warren tech center, or the way some people just whine about problems rather than doing something about them. Their enthusiasm is remarkable, as the rest of the afternoon is filled with a similar mixture of the mundane and high-minded ideals.

Help Wanted, Disruptors Welcome

That vibe also plays against the expected stereotype of a century-old company in the Midwest. But it’s one way GM woos new engineers, according to Brittany Palubiski, who heads up GM’s university recruiting efforts.

GM is hiring big time. It plans to bring in something like 15,000 new full-time employees this year, including many engineers. That pace is likely to continue for years to come, since roughly one-third of the company’s salaried workforce will turn over in the next five years. Meanwhile, the staff at Cruise, which is headquartered in San Francisco, has more than doubled since GM’s acquisition, with many of the hires coming from the same schools that feed Silicon Valley’s tech ecosystem.

The story Palubiski is selling college students is one she could never have pitched a decade ago: That Detroit is a great place to live, and GM is a company with great opportunities for upward mobility, given that one-third of its workforce will turn over in the next five years. It’s also a place where young people can make a difference, a place that’s in the midst of defining the nature of transportation in the 21st century and beyond.

Her boss is Bill Huffaker, who was head of global talent development at Google before joining GM in 2012. “The more I heard about what was happening at GM, the more I was attracted to it,” says Huffaker. “I like to fight for the underdog,” he adds.

Huffaker believes that GM has opportunities that top engineers can’t get in Silicon Valley. “If you’re a software engineer who loves cars, this is the place to work,” he points out. “We have amazing technology and resources, and the cost of living is good. Plus, this is a company in transition,” he continues. “You’re going to work on very real problems at great scale.”

As a relatively new transplant from the Valley, Huffaker knows that GM has a long way to go. Despite all its efforts to be cool, the company isn’t a startup. “If you have that entrepreneur profile, we can’t compete with that,” he says. But he’s encouraged by the progress GM is making, and believes the company is now embracing those looking to shake things up, rather than beat them into submission.

“What I loved about Google was that idea: Anything is possible,” says Huffaker, noting, “Here it used to be, ‘That’s a good idea, but good luck getting it through the purchasing, or the HR, or the IT rulebook.'” If the bankruptcy hadn’t happened, Huffaker observes, “People like me wouldn’t have been accepted here. There would have been organ rejection.”

“We still have a lot of work to do,” say Huffaker. “We are a work in progress. But there’s an energy that we can solve these problems now.”

related video: One CEO Shares How He’s Creating Diversity In Silicon Valley

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(92)