How Billionaires Can Make More Impact With Their Donations

Philanthropy’s deepest-pocketed donors often short-change the causes they claim to care about the most. That’s because while the majority of the world’s wealthiest givers have expressed interest in solving complex social issues like poverty, educational inequity, environmental degradation, and human rights abuses, only 20% follow through with funding of $10 million or more to actually try to create some fundamental change.

In philanthropic industry parlance, that reluctance even has its own term: “the aspiration gap.” As Bridgespan partner William Foster, whose nonprofit and philanthropist consultancy coined that term, puts it: The ambition of philanthropists to put “meaningful amounts of money to move meaningful change into the toughest social problem is as present or more present than ever. The difficulty [for most] is figuring out how to do it.” Many donors simply aren’t aware of all the potential social impact strategies they might deploy.

How to effectively make these so-called “big bets” is a question consuming the philanthropic world today. Dropping a windfall on an organization already doing great work doesn’t matter if the group doesn’t have the capacity to spend it wisely, just as spreading the wealth between too many cause groups might dilute the chances of any of them having enough capital to do anything revolutionary. “The gap is not about desire and what [issue] they want to put money into,” Foster says about major funders. “The gap is about finding places that philanthropists feel they can effectively move the needle.”

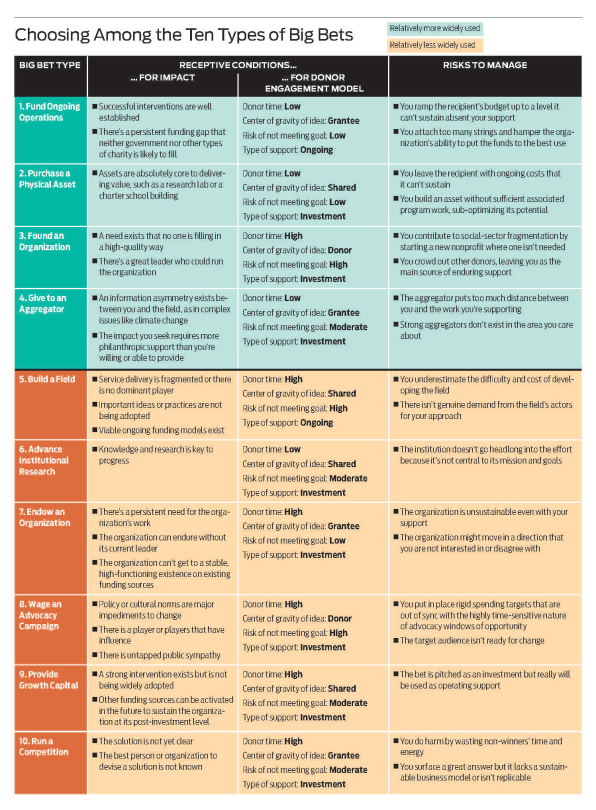

But Bridgespan has crunched some numbers to help with that. After an analysis of 900 big bets placed between 2000 and 2013, the group has identified 10 separate strategies that the biggest and boldest charitable backers have used to spark change. The results, which appear in a Stanford Social Innovation Review report called Ten Ways to Make a Big Bet on Social Change, explores both what’s been tried why under what conditions some wagers seem to especially pay off.

To goal, says Foster, is to create a roadmap of “pathways” for billionaires to consider, which includes factors like how active they might want to be in managing the distribution of their funds, or how to best prop up–or bypass–existing support networks, depending on how well they’re working.

Based on Bridgespan’s analysis, most big bettors give an average of four smaller grants to related initiatives or entities before raising the stakes to an average 10-fold increase in funding. “People aren’t finding something and taking a wild risk and hoping for the best,” Foster says. “The big bets are the product of multiple years of engagement and multiple grants that build understanding and confidence to lay the groundwork.” A classic refrain is “it takes a lot to do a lot,” he adds, but the bets that truly pay off involve substantial patience to first learn how the industry works first.

Among the methodologies that Bridgespan explores, the most obvious are, not surprisingly, more popular than those that seem counterintuitive and perhaps underused. In fact, the top four big bet styles–funding ongoing operations, purchasing physical assets like buildings or land, founding an organization, and giving to an aggregator–account for roughly three quarters what’s being gambled.

That doesn’t mean aren’t strings attached. As Bridgespan reports, giving extra operational funding works best when directed toward a group that might naturally encounter a shortfall because it’s working in an area that excludes common resources, say, public policy advocacy, which can’t receive government support, or charter schools, which often cost more because specialized teacher training, equipment, or low student-to-teacher ratios.

Building facilities or securing land for groups seems like straightforward enough actions, but also works best for places that truly need the associated buildings or real estate to accomplish their mission, like “community health centers, charter schools [and] conservation efforts” notes the report. In some cases, it might even make sense to split such gifts up, earmarking a share to any uptick in associated operating costs.

To that end, founding your own organization sounds dreamy, but should really only be done if there are no other players doing “good enough” in the space. Otherwise, you’re wasting valuable cash and brainpower when you could just invest directly with those who already know the space. When there is that gap, however, a new organization can do wonders. For instance, ProPublica, a nonprofit news organization that isn’t affected by declining circulations, continues to publish important investigatory work.

On the flip side, some of the lesser used concepts, including “building a field” and “wage an advocacy campaign,” might need to be employed more often. There are instances of these being incredibly successful although they can take more time and imagination to roll out.

Take field-building, which includes historical successes, like the Rosenwald Schools program, which launched around 5,000 new schools in the 1930s to bring more educational opportunity to African-American students in the South. That dramatically improved the field of equal educational access providers. More recently, the Rockefeller Foundation, Omidyar Network, and USAID have grown interested in impact investing substantially by supporting the Global Impact Investing Network, which works to increase the accessibility of the practice. In both cases lots of collective, often small-scale actions have led to long-term gains.

Philanthropists may have shied away from advocacy efforts in the past because they envision their names associated with hot-button, perhaps intractable issues like gun control. But there plenty of other substantial, less politicized issues where concentrated donations have made major change, including Dallas billionaire Lyda Hill’s work to address the health crisis of antibiotic resistance that has curbed some livestock-raising practices and changed what’s on the menu at restaurants and in grocery stores.

One largely underused tactic that could prove effective would be to create organizational endowments to cause-related organizations, which could then manage the wealth and distribute annual grants at their discretion. “Almost every university gift of significance is either an endowment or a physical asset, both of which are perpetuities,” Foster says. “People don’t do that for homelessness organizations or environmental groups.” Perhaps that may start changing now. Find the full report and playbook here.

Philanthropists often don’t actually give enough to create the change they are advocating for. A new report tells them how to be more effective with their dollars.

Philanthropy’s deepest-pocketed donors often short-change the causes they claim to care about the most. That’s because while the majority of the world’s wealthiest givers have expressed interest in solving complex social issues like poverty, educational inequity, environmental degradation, and human rights abuses, only 20% follow through with funding of $ 10 million or more to actually try to create some fundamental change.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(30)