I Built A Bot To Apply To Thousands Of Jobs At Once–Here’s What I Learned

I have a great job, and there’s no rush to leave. As a director at a national nonprofit I’ve built some fantastic teams, but over the past year they’ve gotten so good at what they do that I’ve begun to wonder whether I’m still needed. So I started slowly casting about for new challenges, initially by applying (perhaps naively) to openings at well-known tech companies like Google, Slack, Facebook, and Squarespace.

Two things quickly became clear to me:

- I’m up against leaders in their field, so my resume doesn’t always jump to the top of the pile.

- Robots read every application.

The robots are “applicant tracking systems” (ATS), commonly used tools for sorting job applications. They automatically filter out candidates based on keywords, skills, former employers, years of experience, schools attended, and the like.

As soon as I realized I was going up against robots, I decided to turn the tables–and built my own.

How I Built A Job-Application Machine

I’m no engineer but I play with technology a lot. I’ve been known to find ways to automate things (social media, data processing, web content, etc.) out of boredom or creativity or both. So I cobbled together a Rube Goldbergian contraption of crawlers, spreadsheets, and scripts to automate my job-application process, modestly referring to it as my “robot.”

My robot aggregated hiring managers’ contact information, then submitted customized emails with my resume and a personalized cover letter. Soon, I was imagining myself telling the story of how I’d turned my job search into a super-precise job firehose.

I tracked how many times my cover letter, resume, or LinkedIn profile was viewed. I also tracked email responses (including from autoresponders). It wasn’t a particularly elegant mechanism, but it was ruthlessly efficient. The first time I fired it up I accidentally applied to about 1,300 jobs in the Midwest during the time it took me to get a cup of coffee across the street. I live in New York City and had no plans to relocate, so I quickly shut it down until I could release a new version.

After several iterations and a few embarrassing hiccups, I settled on version 5.0, which applied to 538 jobs over about a three-month period.

Not Even Robots Read Resumes

To cut to the chase, it didn’t work. I’m still looking for the right gig–and it may not shock you to hear that my robotized approach hasn’t paid off.

But before you remind me that I did exactly what every career coach and recruiter tells jobseekers not to do, hear me out: I wasn’t just blasting the same content to every imaginable job listing–far from it. I tested different email subject lines, versions of my resume, and cover letters. I built my robot in order to adjust and optimize as many variables as possible when applying to each new job, just like an individual might, one application at a time.

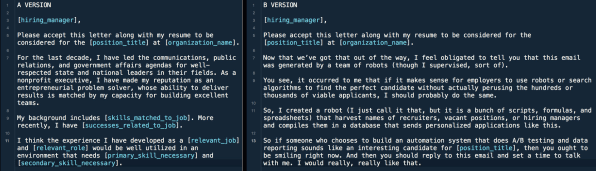

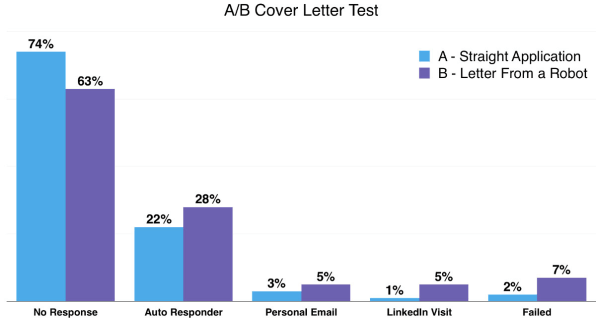

But while I saw some variation in response, there wasn’t much. It seemed like nothing made a difference in actual human reads. One A/B test used a normal-looking cover letter and contrasted it with a letter that admits right in the second sentence that the email was being sent by a robot:

Now, one of those letters should have performed either a lot better or a lot worse than the other. For my purposes, I didn’t care which; I just wanted to stand out from all the other applicants. But it didn’t seem to matter because, as far as I could tell from this experiment and others like it, nobody reads cover letters–not even other robots like ATS algorithms.

Related: Cover Letters Are Dead–Do This Instead

By targeting internet companies in particular, I’d chosen an industry with a high likelihood of reliance on resume-processing algorithms. And without the tech pedigree (and corresponding keywords) to sneak by those filters, I had a steep hill to climb, robot or no robot.

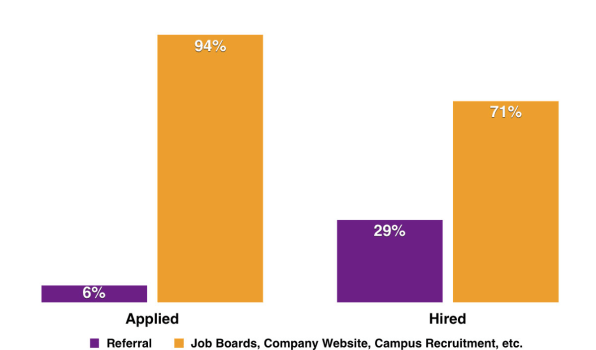

Friends were quick to point out the obvious reason that this approach wasn’t working. Most told me I had to know someone who would pass my resume along to a hiring manager. By trying to game that system, I inadvertently learned how powerful it really is. One 2014 study found that 30%–50% of hires in the U.S. come from referrals, and referred candidates are over four times more likely to be hired than non-referrals. According to one hiring consultant’s estimate, referrals lead to a whopping 85% of critical jobs being filled.

It’s Not Just A “Numbers Game”–It’s Many Numbers Games

But even if companies give preference to employee referrals, they must be on the lookout for candidates with unique qualifications–or so I thought.

I asked Scott Uhrig at Agile.Careers, a coaching program for high-tech executives, how a nontraditional candidate would fare in a fiercely competitive job market. He explained that it’s easy to find candidates that fit cleanly within a mold. Beyond that, though, “recruiters are usually not very helpful; they are looking for candidates in the center of the bullseye.” From his vantage point, recruiters don’t have time to search for something outside the norm.

Amy Segelin, president of the executive communications recruiting firm Chaloner, put it a different way: “Out-of-the-box hires rarely happen through LinkedIn applications. They happen when someone influential meets a really interesting person and says, ‘Let’s create a position for you.’”

So that was two strikes against the time-honored tradition of submitting a resume and crossing your fingers. But I wasn’t just handing over a resume. I was handing over a lot of resumes. The law of large numbers suggests that something should get through the ATS and stand out, even next to candidates whose buddies bumped their resumes up to the top of the pile.

Uhrig explained that there was another numbers game at play, too. “Roughly 80% of jobs are never posted–probably closer to 90% for more senior jobs,” he told me. “The competition for posted jobs is insane. ATSes do a horrendous job of selecting the best candidates, and–perhaps most important–the best jobs are almost never posted.”

Other recruiters I’ve spoken to since running my robo-experiments suggested that most positions on job boards were either posted by an HR person who’s since changed jobs, or they have already been filled. (Or, in the case of a lot of tech companies, they’ve already decided to hire someone on an H1B visa but need to post the position to fulfill requirements.)

In short, it doesn’t matter if you submit two, three, or 10 times as many applications as the average candidate–they’re rarely going to work out in your favor, for factors beyond your (or your robot’s) control.

Less Applying, More Networking

So where has this left me, aside from somewhat disheartened? Well, for one thing, it leaves me a little bit wiser. As my faith in the front-facing application process eroded into near oblivion, I learned three lessons by robotically applying to thousands of jobs:

- It’s not how you apply, it’s who you know. And if you don’t know someone, don’t bother.

- Companies are trying to fill a position with minimal risk, not discover someone who breaks the mold.

- The number of jobs you apply to has no correlation to whether you’ll be considered, and you won’t be considered for jobs you don’t get the chance to apply to.

Maybe I didn’t need an elaborate bot-driven scheme to find that out. And maybe, somewhere along the way, I became more interested in what the data says than in whether or not a robot could actually find me a job. But the project wasn’t entirely without success. Forty-three companies ultimately reached out for follow-up interviews, and I actually talked to about 20 of them. In virtually every case, though, the companies were on the smaller side (less than 50 staff) and not a single one had an ATS in place to filter resumes.

I’ve been transparent with almost all of the interviewers about my process, and while I worried it might be a real turnoff, they’ve all responded positively so far; I’ve even landed a few consulting gigs from it. But in the meantime, I’ve given up on applying for jobs the old-fashioned way–both manually and robotically. I’m now scaling back my nonprofit role to three days a week and taking some time to meet interesting people in person and see what I can learn from there. Eventually, I’m hoping, one of those interesting people is going to ask for my resume so they can put it on top of a pile somewhere.

Robert Coombs is a communications and web executive in Brooklyn, New York. His Instagram is definitely not run by a robot.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(117)