IBM Wants To Build AI That Isn’t Socially Awkward

Though artificial intelligence experts may cringe at the portrayals of humanlike AI in science fiction, some researchers are nudging us closer to those visions. “I think it’s useful that your user interface not only understand your emotions, your personality, your tone, your motivations, but that it also have a set of emotions, personality, motivations,” says Rob High, the CTO of IBM Watson. “I think that makes it more natural for us.”

Last month, High’s company unveiled Project Intu, an experimental platform that allows developers the ability to build internet of things devices using its artificial intelligence services, like Conversation, Language and Visual Recognition. Someday, the system promises to let programmers create a staple character of sci-fi: the gregarious, hyper-connected AI like J.A.R.V.I.S. of Iron Man, KITT of Knight Rider, or Star Wars‘ C3PO.

But this isn’t Westworld. High isn’t talking about a robot that’s conscious or sentient, with genuine feelings, but rather a “cognitive” AI that can analyze the mood and personality of a user and adjust how it expresses itself—in text, voice, online avatars, and physical robots. The result, he says, could transform industries like retail, elder care, and industrial and social robotics.

Intelligent Agents

At IBM’s 2016 Watson Developer Conference in San Francisco last month, Australian oil- and gas-drilling company Woodside showed an onscreen question-answering AI built with Project Intu. Willow, as she’s known, is an animated abstract character with a sassy British voice. Her job is to take voice instructions and quickly scour hundreds of linked computer systems to retrieve engineering documents and detailed data, such as the current location of a tanker ship or the maximum weight of a helicopter that can land on an oil-drilling platform.

“Any sci-fi movie, any comic book you’ve ever read, this is the way that we have always wanted to interact with machines,” says Russ Potapinski, Woodside’s head of cognitive science.

High offers automated customer service as a prime example of the need for AI that can read human emotions. “The difference between somebody who’s angry versus somebody who’s disappointed matters. Somebody who’s angry, chances are they’re in a pretty irrational state of mind…you’ve gotta get them back to the point where they can be rational,” says High. “Somebody who’s disappointed… they don’t like what you did, but they’re not irrational about it.”

There are limits to what an onscreen bot can do, High acknowledges, which is why IBM is determined to go further. “If you ask me a question about direction, it would be hard for me to answer that without being able to point,” he says. “But it’s not just [hand] gestures. It’s body language, it’s facial gestures… All that adds to your understanding of what I mean.”

Project Intu is not the first effort to build empathetic-seeming bots, and IBM is hardly alone when it comes to artificial intelligence research. Salesforce, Google, Facebook, Amazon, and other large tech companies are also investing heavily in their own AI systems. But as an open-access cloud service, Intu promises to let anyone, even a garage programmer, create socially sophisticated AIs that can be useful for communicating with humans who need answers, be they inside a company or customers who call or chat with customer service questions. “We deliver tools, and other people turn them into actual running examples,” says High.

Customers are encountering more nonhumans when trying to resolve certain service issues, with mixed results. In a June study with a dozen participants by U.K. media agency Mindshare, which included Watson-powered bots, about 60% of people said that they would consider using an AI bot to get in touch with a brand, but as many of them agreed that “it would feel patronizing if a chatbot starting asking me how my day is going.” And half of them agreed that “it feels creepy if the chatbot is pretending to be human.”

A much larger survey of 24,000 respondents across 12 countries, conducted by research firms Verint, Opinium Research, and IDC looked at all the ways customers communicate with companies. It didn’t specifically compare humans to bots, but it did reveal that telephone support is most popular and chat is least loved. (Think about the current stilted state of conversation with Siri or Alexa.)

That IBM debuted Project Intu the day after an election that evoked a lot of human emotion wasn’t lost on High. “If I’m already depressed because of some political situation that I’m aware of today, I may not want this thing to be entirely chirpy to me this morning, right?” he says.

Project Intu builds on technologies that IBM has already developed. An existing service called Watson Tone Analyzer, for instance, reads through text like social media posts to judge “emotional sentiment.” It even helped a musician, Alex da Kid, write some moody songs for his recent EP.

Automated sentiment analysis isn’t brand new. It has been offered by companies like Adobe and Lexalytics to understand consumer opinions on platforms like Facebook and Twitter. In fact there are dozens of companies just doing text-based analysis, such as Viralheat for social media, Api.ai and DigitalGenius for conversational interfaces, Textio for HR, and Receptiviti for personality profiling.

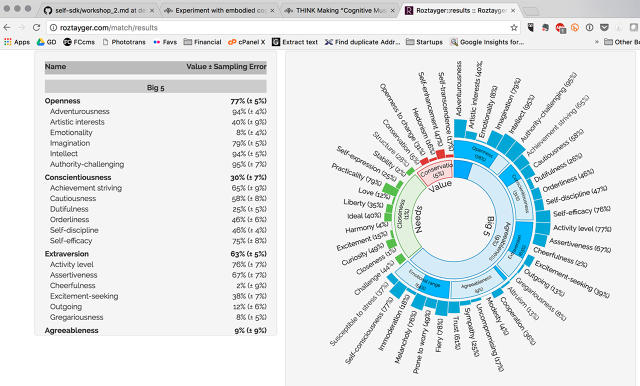

Another Watson tool incorporated into Project Intu, Personality Insights, promises to analyze text like email or Twitter and Facebook posts to ferret out people’s traits. Online retailer Roztayger has an experimental tool called Designer Match that uses Watson to recommend products that suit their personality. It found me to be pretty dour, based on my businesslike Twitter feed. Designer Match might understand me better if I’d given it access to my Facebook account, but I didn’t want to share that much, especially not with an AI I’d only just met. The privacy implications of Project Intu are considerable (more about that later).

Watson’s speech engine can also feign some personality in its responses. “We can adjust things like its cadence or breathiness or its pitch, make it sound more like an old person or a child,” says High. “We can put inflection in it that makes it either happier, you know lighter, lilting, or more apologetic.” And IBM already has a bunch of tools for building chatbots.

Robots For Therapy, Companionship, And Health Advice

To attempt to achieve emotional and empathetic interactions with humans, Intu needs to go beyond just talking, be it through a chatbot or a voice-based assistant like Amazon’s Alexa. One advanced version of Intu, says High, might be a more sophisticated online avatar—an animated character that more closely resembles a real human assistant—without going too far into the uncanny valley.

A similar approach is at work at the U.S. Dept. of Defense, which funds a project called Virtual Humans that was developed by the Institute for Creative Technologies at the University of Southern California. The video game-style characters role play with soldiers to practice their interpersonal skills with colleagues.

They also provide counseling. The system reads tension in voice, word choice, posture, and facial expressions to assess someone’s mental state. Professor Jon Gratch, who runs the Virtual Humans program at USC, says that some service people are more comfortable opening up to a virtual human than to a real one who may be judgmental. Given the cost and ever shakier status of mental health care coverage, AI may fill a gap that human professionals can’t.

“I think it goes back to the same theory, the same premise,” says High about Virtual Humans, “which is that, for us to effect a natural interaction between humans and machines, it has to be more than simply a running set of text.” (Virtual Humans draw on prerecorded dialog, but USC is working toward AI that can converse extemporaneously.)

Watson launched in the health care field, and that business now accounts for two-thirds of the Watson unit’s employment. Much of the focus has been on analyzing medical and genomic data to help doctors make decisions and design tailored therapies. But other companies, such as iDAvatars, have also been using Watson to power virtual assistants that communicate directly with patients.

IBM is joining a trend. Japan has long been the land of social robots. They’re now coming across the Pacific, bringing over robots like Pepper, the doe-eyed android that serves as a sales assistant in stores. It monitors video and audio to distinguish and respond to four human emotions: happiness, joy, sadness, and anger. High’s lab is connecting Pepper and similar robots with Intu to make them more socially adept.

“Imagine eventually robots in your home, social robots, or in your bank lobbies or store lobbies or anywhere else that you go,” says High. He extends “robot” to mean other kinds of machinery. “You can imagine your room itself as a device,” he says. “It can have control of your lights and your shades and appliances in your room.” That sounds like J.A.R.V.I.S., the omnipresent AI that helps Tony Stark control his house, workshop, even his Iron Man suit. High agrees, though seems a tad uncomfortable with a comic-book comparison.

What about the biggest machine people may own, one that’s always getting more “intelligent”? “When you get into your car, it’s not just about driving someplace,” says High. The experience extends to the music, the seat position, the temperature, the nav system. “Now if all of that could be orchestrated, so that when you get in your car, it feels like it’s alive to you, that would be profoundly different,” he says.

I can’t not allude to KITT, the wise-talking, robotic car that sped David Hasselhoff on crime-fighting missions in the 1980’s show Knight Rider. Again, High hesitates at a Hollywood reference, but concedes, “That’s the idea that it could progress to.” (Though he may not mean the crimefighting part.)

That model could be problematic if KITT drives out of cellphone range, since Watson is a web service. It might be able to adjust the seats from time to time, but it had better not be in charge of the collision avoidance system when the car hits a wireless dead spot. It wouldn’t be: At the moment, self-driving systems all depend upon a computer in the car. A less-dramatic example: I tried to chat with some basic Intu bots running on laptops, but overtaxed Wi-Fi at the conference left them close to crippled. Here IBM may be bucking a trend of bringing AI right down to devices. Even recent-model smartphones are now capable of running sophisticated neural networks on their CPU and graphics processors.

Another roadblock could be privacy. High describes AI’s that build long-term relationships with users, such as customers of a bank. From a customer’s life events—say, shopping that indicates the birth of a child—an Intu bot could know that they may be looking to buy a larger house, for instance.

If people are concerned about companies collecting their personal data, how will they feel about collecting personality data? I put the question to High, who says the purpose would be to use understanding of personality only in the moment of conversation, not to retain it and build a profile. “I think it’s a separate issue, and certainly one of concern, that we all need to be aware of as to what people do with that information if aggregated and exploited for marketing purposes.” But as High says, IBM only makes the tools. It’s up to its clients how they use, or abuse, them.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(49)