Inside Apple And IBM’s App Making Machine

On a July day in 2014 some people from IBM and Apple got together in a room at Apple headquarters in Cupertino, California to start work on their recently announced business app creation partnership. The fact that the two companies were working together at all sounded a little unlikely; IBM, after all, was once cast in Apple mythology as the big, slow, and safe antithesis of everything Steve Jobs wanted his company to be. At least in the consumer space, the two were bitter rivals.

Then Apple won personal computing. In the new millennium business was increasingly done on mobile devices—often personal devices brought in by employees—running apps served from the cloud. People began expecting work applications to possess the ease of use and design sense that they saw in their personal apps.

The IBM people brought with them to Cupertino that day a mobile app they’d been working on—a fuel calculation app for airline pilots—that they thought might serve as a starting point for the partnership. It was built by IBM people, who had also built some powerful data analytics into the background. The IBM people hoped the Apple people would see it and be impressed, and then the two companies would continue building the app together.

But that’s not what happened. IBM’s app—all 40 screens of it—was a bloated mess. One Apple UI expert in the meeting said simply “that’s not going to work,” a person who was there told me. Pilots, the expert said, would not go through 40 screens in an app, even if they were currently doing the same tasks on paper.

So began the Apple/IBM partnership, which is officially known as IBM MobileFirst for iOS. IBM’s fuel app didn’t end up launching the partnership, but the Apple UI expert’s criticism of it summed up the design sense that would guide the creation of IBM MobileFirst apps going forward. It also said a lot about the what the dynamic of IBM and Apple’s working relationship would be.

Unlikely Partners

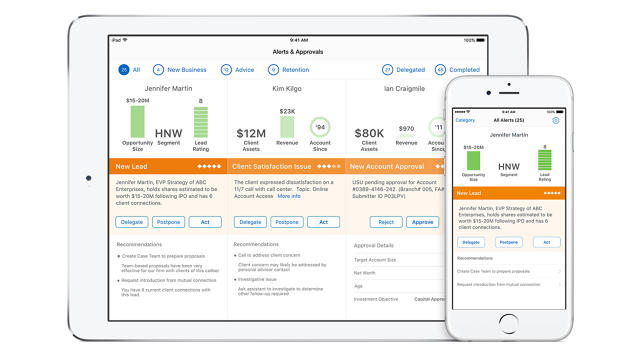

The July 15, 2014 press release announcing IBM MobileFirst for iOS described a combination of Apple’s expertise in mobile computing with IBM’s deep understanding of specific industries and their analytics, workflows, and data needs. The two companies said they would build 100 apps in verticals like travel, health care, retail, and energy. By December 2015 the two had reached that goal, and they’ve continued developing apps—both custom apps and ones that could be used multiple clients.

“It’s strategically very powerful for both companies, and we think it’s a great fit,” Apple VP of product marketing Susan Prescott told Fast Company.

Apple CEO Tim Cook, who early in his career spent 12 years working for IBM, told CNBC on the day the partnership was announced that he began chatting with current IBM CEO Ginni Rometty two years prior and found some commonalities in the challenges and opportunities their two companies face. They soon assigned teams from both companies to look into ways Apple and IBM might work together. The teams returned a number of ideas, and an app collaboration partnership was one of them, Cook said in the CNBC interview.

And, at least in theory, IBM MobileFirst for iOS could open up a big market for Apple. Big IBM clients that decide to use one of the co-developed apps will obviously need lots of Apple devices on which to run them. And the addressable market is pretty huge. A Wandera/Redshift Research report earlier this year said enterprises will pay about $1,840 per employee per year for mobile devices when carrier, IT, security, and services are factored in. About 21% of that is pure hardware costs. Multiply that by the thousands of people employed by corporations and you begin to see the opportunity.

Working Together

This is how the IBM general manager for the Apple partnership, Mahmoud Naghshineh, describes the two company’s day to day working relationship: “Apple is the great designer who takes ownership of the app. The IBM person knows the client’s business challenges and back-end systems.”

No doubt that’s accurate, although it’s the IBM people who seem to do most of the work. They’re the ones who bring in the clients, sell the apps, and plan what types of apps to build. IBM designers and coders around the world do most of the actual app building. “I don’t want to say that [Apple] is not doing the the design, but they’re not sitting down at the computers doing the design,” says Sue Miller-Sylvia, VP of IBM’s MobileFirst for iOS Solutions program.

For many clients, IBM even acts as an Apple hardware distributor. The company offers a number of ways for its clients to acquire large numbers of iDevices. Customers can buy outright, lease, or sign up for a buy-back program that lets them trade up for new devices every year or two. Customers can also access IBM cloud-based device management, security, and mobile integration services.

Still, Apple is bringing something to the partnership that no other company can. For many people, the company defined the look and feel of mobile computing. And in the Bring-Your-Own-Device era, someone might be using an enterprise app on a smartphone at 4:58 p.m. and using a personal app on the same device at 5:02. That leaves people directly comparing work and consumer tools, and less likely to tolerate ugly enterprise work apps—especially on the small screens of mobile devices.

That’s the context in which the IBM/Apple partnership happened. “In a very basic sense, it’s all about making the apps people use at work more congruous with the apps they use on their phone in their personal lives,” Miller-Sylvia says.

Apple’s role in the MobileFirst partnership involves mandating that the apps be simple, and pointing out the native features that they should be using. The company’s designers hold weekly calls with the IBM people building the apps to make sure design principles are being respected. “They are the ones that look at it and say ‘You know what, that’s not going to work, somebody’s not going to do five taps to get to that particular screen,’ or ‘you need to follow our Human Interface Guidelines.’ It’s always been advice and counsel, and making sure it was something they would put their stamp on as well,” explains Miller-Sylvia.

The iPad Takes Flight

A few months ago, a woman on an Air Canada flight into London’s Heathrow airport got upset because the flight was late and she thought she might miss her connecting flight. The passenger—who was in tears, according to a flight attendant—had lost her boarding pass when getting on the plane in Frankfurt. Now she was fretting about landing at a big, strange airport and not knowing her way to the connecting gate.

The information the flight crew needed to help the troubled woman wasn’t on the passenger information list (PIL), the big sheaf of printer paper flight attendants normally use to manage the flight. But the good news was that Air Canada had just begun using the MobileFirst Passenger+ app, remembers Air Canada service director Suzanne Strong. Strong is one of about 1,300 Air Canada service managers for whom the airline leased iPads from IBM to run the app.

Strong said she approached the passenger with iPad and app in hand and addressed her by her name. “Someone with just the PIL wouldn’t have been able to do that,” Strong said. “We often have no idea who they are.” After the woman got some information about her gate and how to get there, she calmed down and cheered up. Just being addressed by her first name and getting the personal attention seemed to help a lot, Strong says.

In Passenger+, a flight attendant can see which passengers are traveling with babies, require special meals, or are entitled to special perks. If a flight in progress is delayed, the app can provide information on its impact on passengers. Flight attendants can use the app to find solutions while still in the air, such as booking a new flight for a passenger who has no chance of making a connection. Managing such information at large international airports can be particularly cumbersome on paper, says Strong.

Air Canada is currently in phase 1 of a three-phase implementation of the app. Air Canada’s Passenger+ app now contains all the information in the PIL, and the airline is in the process of adding additional additional data. Where the PIL contains only information about passengers who have special needs or requests, Strong told me, the Passenger+ app contains information about all passengers on the flight. The information is currently static, but the app will eventually be able to update it in real time during the flight.

In the second phase, Passenger+ will starts to look more like a CRM (customer relationship management) system, Air Canada senior director of operations, information systems, Steve Bogie told me. It’s at this phase that flight crew will be able to identify VIP passengers and offer them personalized TLC. In the third phase, Passenger+ will incorporate mobile payments, allowing the airline to sell add-on products and services to passengers. This could mean anything from premium wines to noise-canceling headphones to first-class upgrades.

Apple, IBM, Designers, Devs, and Real People

When IBM gets an order for an app such as Passenger+ from one of its enterprise clients, it invites key members of the client’s team in for a three-day workshop at Apple’s Cupertino campus. At the beginning of Passenger+ development, Air Canada sent IT people, managers, and flight attendants to the workshop to hash out the basics.

At the workshop, some manager types like Naghshineh and Miller-Sylvia are in the room. Apple will have a few of its designers there, as will IBM.

In addition, Apple requires that end users from the client—such as flight attendants in the case of Passenger+—are there to provide their unique view of what they need from an app. The company believes that this step is essential for prompting an immediate “Oh I know how to use that” reaction from the people who will actually use an app, one app designer told me. It also cuts way down on the training time needed to initiate new users.

Miller-Sylvia told me that this insistence from Apple doesn’t always play well. “You can’t imagine how much push-back we get from the client, because the managers think they know,” she says. But “all of the transformation comes from the end users being involved. There’s so many things that they do, and the managers end up getting surprised in the sessions and saying, ‘We had no idea.’”

During one workshop, one of the end users explained: “When I need to do that, I just write it on my hand,” Sylvia-Miller recalls. “And the manager was like, ‘you what?!’” It’s exactly this kind of nitty-gritty day-to-day work reality that gets exposed during the three-day workshops—things a middle manager might never know about.

The first day of the workshop is spent mainly talking to end users about their workday and about how the app might best be integrated into the work. After that, the Apple and IBM designers begin to develop actual app screens that carefully reflect the users’ workflows.

By the end of the three-day workshop, the participants will have created the first few screens of a new app. Naghshineh told me that after the workshop is completed, many of the apps are designed and coded by the iOS and Swift developers in IBM’s “App Garage” in India. The Passenger+ app, however, was developed for the most part in an IBM development shop in Toronto. IBM also has development facilities in Atlanta and Chicago.

Apple Flavor

Even before the workshop in Cupertino is over, the designers begin to apply design elements that have a familiar iOS look to them.

The MobileFirst apps use design artifacts that users might recognize from within iOS or in an Apple app they run on their phone. For instance, the Passenger+ app uses “badging” (small red dots with a number within) over a seat to signify that the passenger sitting there has a number of special needs or requests that might require attention from the flight attendant.

In another app, the designers used a familiar toggle bar at the top of the screen to switch between two views. It was familiar because the same toggle bar is used at the top of the iPhone’s Recent Calls screen to switch between “all” calls and “missed” calls. Miller-Sylvia calls that a perfect example of a design trick used to help people move seamlessly from their personal apps to their work apps.

IBM’s app developers are required to know and use Apple’s Human Interface Guidelines to guide the look, feel, and flow of the apps. “We do checks against that when we train our people,” Miller-Sylvia said. “We say, ‘This is your bible.'” IBM has also been been building a book of best practices during its work with Apple, with elements and design templates and artifacts that can be used and re-used in building apps.

Traditionally, IBM has immersed itself in the the business realities of many different industries, Miller-Sylvia explains. It has deep analytics experience and expertise. “Apple has really taught us to step outside of that for a minute and really look at the simplicity,” Miller-Sylvia said.

For instance, Apple’s guidelines dictate that it should take users just one or two taps to get to what they need at any given time. Users should also be able to get to everything they need to complete a specific task (like estimating pounds of fuel for a flight) from the app’s opening screen.

To Apple, a big part of simplicity is scope. The company’s designers want to completely understand what the end user will be doing at the moment they use the app. Building in functionality that addresses tasks beyond that moment may overburden the UX with too many tab bars and links to other tasks. Apple would rather make a series of smaller, purpose-built apps than one big one that tries to do everything.

This is often a very new concept for IBM’s clients, who often come in with the idea that their app should be all things to all people at all times. Miller-Sylvia remembers one woman who came to the workshop in Cupertino carrying a 400-page binder with everything she hoped to wedge into an app.

“We said, ‘Just trust us for a few days, just let it go’,” Miller-Sylvia told me. The woman ended up throwing her binder away, and she left Cupertino happy after starting a new version of the app from scratch.

In the past, Apple has never been considered a go-to enterprise vendor in the way Microsoft and IBM are, a notion Cook acknowledged in the 2014 CNBC interview: “. . . the reality is, that the penetration of these businesses and in commercial in general for mobility is still low.” When Apple devices show up in enterprise workplaces, more often than not it’s because employees buy them for personal use then bring them to work. Apple’s association with IBM may give its name a more credible sound in the ears of Fortune 500 CTOs.

As successful as Apple has been in the 2010s, iPad sales have been a sore spot. Five years ago, sales of the devices contributed 16% of Apple’s revenue; today they contribute about 9%. It’s difficult to gauge whether or not the MobileFirst for iOS initiative has begun helping reverse that trend, but then the initiative is only a bit over two years old. Getting whole industry segments turned on to doing their work with iPads and mobile apps doesn’t happen all at once.

Talking to Apple and IBM people for this story, I got the honest impression that the initiative still has a lot of juice behind it—perhaps a bit more so on the IBM side. Apple is clearly invested in addressing the enterprise, as it’s shown by forming partnerships with other big players like SAP and .

Perhaps most importantly, the Apple and IBM people seem to be pulling in the same direction. People I spoke with from the two companies were reluctant to talk about any disagreements or growing pains in the relationship, but they talk in very similar terms about the roles of the two partners, about the initiative’s guiding principals, and about its near- and long-term goals. Miller-Sylvia told me that if you were to eavesdrop on one of the app workshops on Apple’s campus (good luck with that) you wouldn’t be able to tell the Apple and IBM people apart.

Yes, the world has changed a lot since that day back in the ’80s when Steve Jobs was photographed standing in front of the IBM sign flipping it the bird.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(48)