Inside IFTTT’s Plan For A More Harmonious Internet

Imagine you left the house for the day and forgot to lock the doors. Although you’ve installed a smart door lock, and your Ecobee thermostat’s room sensors can recognize when no one’s home, the two devices can’t communicate with each other, so the thermostat can’t lock the doors when it realizes the house is empty. Until you remember to trigger the locks yourself, the doors remain open.

This is the kind of dilemma that IFTTT (which stands for “If This Then That”) wants to eradicate. For the last six years, the startup—whose name rhymes with “gift”—has acted like a switchboard for internet services, letting them work together in ways the service providers never anticipated. IFTTT can automatically send Gmail attachments to Dropbox, log the user’s favorite Pandora tracks in Evernote, text a neighbor when Nest Protect detects a smoke emergency, or flash a set of Philips Hue light bulbs when someone presses a Ring doorbell. So far, IFTTT users have created 41 million of these connections—known as “Applets” or “Recipes”—using IFTTT’s apps and website, collectively triggering them more than 1 billion times per month.

But as it tries to build a sustainable business, IFTTT has been backing away from its do-it-yourself roots, and catering more to the companies whose services it connects. Those companies can now advertise IFTTT Applets directly within their own apps, so users can discover potential connections without passing through IFTTT’s own app or website. The connections between services are also becoming more complex, so that a single Applet can work with three or more services at the same time. In exchange for these new powers, IFTTT has launched a paid subscription program, so that any company can use IFTTT to hook up with other services.

“We want to become a PayPal for access,” says Linden Tibbets, IFTTT’s founder and CEO. “A trusted third party that facilitates an exchange from one service to the next.”

The question, then, is whether those companies truly value a more compatible internet—enough that they’re willing to pay a middleman to make it happen.

Reshaping The Digital World

IFTTT was more of a belief than a product when Tibbets started working on it in 2010. He was fascinated with people’s ability to discover hidden utility in their physical environment—the pencil tucked behind the ear, the bottle cap as makeshift ash tray—and set out to ready the internet for similar discoveries.

In his first blog post, Tibbets described IFTTT as “digital duct tape” for tying two services together. Early uses included getting a text message when the weather forecast showed rain, auto-posting Flickr photos to Facebook, and logging Foursquare check-ins to Google Calendar.

“We started out with this fundamental belief around confidence,” Tibbets says. “What we feel is that people should have this innate confidence that they’re in control, and that the things they surround themselves with really aren’t bars to their prison cell.”

That notion quickly caught on with internet power users, who had created more than 1 million recipes to connect their apps and services by mid-2012, roughly nine months into IFTTT’s public launch. Investors, wooed by Tibbets’s belief in a more connected internet, came knocking, and in December 2012, IFTTT raised $7 million in a Series A funding round led by Andreessen Horowitz.

“Linden really struck us as having a lot of foresight back in 2012,” says John O’Farrell, a partner at Andreessen Horowitz. “He really saw this explosion of services and devices coming.”

But while adoration for the product abounded in Silicon Valley, Tibbets says IFTTT was becoming a victim of its own success. The idea of creating original internet recipes resonated with a select audience, but remained an obtuse concept for the mainstream users that IFTTT needed to grow a business.

“We felt like the ‘if this, then that’ concept, as exciting as it was, really spoke to a sophisticated power user,” Tibbets says. “There was no way in which we could make it simpler and still maintain this idea of connecting two or more things together.”

IFTTT would spend the next four years figuring out how to balance those two opposing interests.

Missing The Mark

Some signs of this conflict—simplicity versus complexity—emerged in 2014, when IFTTT raised another round of funding, this time for $30 million. Tibbets said at the time that the investment would help IFTTT further the internet of things—the concept of connecting ordinary objects to online services. People were starting to bring their door locks, power outlets, garage door openers, and thermostats online, and IFTTT wanted to give them a common language.

“The way we see the Internet of Things playing out, there’s going to be a need for an operating system that’s detached from any specific device,” Tibbets told the New York Times in 2014. “What we’re doing now is the foundation for that.”

Even with a bigger focus on those smart home products, IFTTT struggled to make the case for itself as a mainstream service. The company launched a trio of new “Do” apps that were supposed to be simpler than the usual IFTTT recipes, letting people quickly trigger an action on the internet by pressing a button, taking a photo, or jotting down some text on their phones. But these apps floundered after their early 2015 launch. Tibbets says that while Do app users were highly engaged, and came up with some novel uses, most people weren’t interested in downloading three entirely new apps from the App Store. IFTTT discontinued them a couple of months ago, and rolled their functionality into the main IFTTT app.

“One of the things we learned, along with a lot of other companies that learned this the hard way at the time, is that it’s really hard get anybody to download even one app,” Tibbets says.

While IFTTT struggled to build a large mainstream business, the company also looked at monetizing its core power users. After raising the additional venture funding, Tibbets started dropping hints about a premium subscription service, which would add extra features such as connections to multiple Twitter or Instagram accounts. At an industry conference in October 2014, Tibbets said the paid service would be ready in the “coming months.”

Those plans never came to fruition, because IFTTT finally realized that appealing directly to consumers wasn’t the answer. The real customers were the services that IFTTT had been connecting all this time.

“Flipping The Audience”

In its early years, IFTTT didn’t have any direct relationships with the services it was mashing together. Instead, IFTTT tapped into those services’ existing developer tools, which were available to anyone.

“No one at Flickr or Twitter or The Weather Channel had any knowledge of who I was or what IFTTT was doing,” Tibbets says. “We were just somebody using their API.”

But as IFTTT began to make a name for itself, it started getting requests from companies that wanted their services to be supported, and were even willing to pay for the privilege. While IFTTT accommodated some of those requests on a case-by-case basis, there was no way for companies to plug in support on their own. So around the time that IFTTT received its Series B funding, the startup began working on a new strategy, allowing internet devices and services to add their own IFTTT support.

The IFTTT Partners program launched in early November after months of private testing. For $199 per month, companies can list themselves in IFTTT’s service directory, and embed recipes—now called “Applets”—directly into their own apps and website.

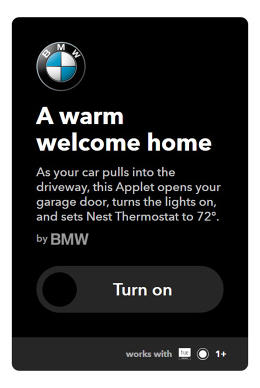

IFTTT is also letting these partners create more powerful connections, starting with multiple outcomes from a single triggering condition. One early example: When a BMW car owner gets close to home, IFTTT can open the garage door with Garageio, start warming the house with a Nest thermostat, and turn on the Philips Hue lights.

In the future, IFTTT will also allow for multiple triggering conditions, or “queries.” In the garage door scenario, for instance, IFTTT might be able to turn on some music if no one else is home yet, or post a “mom’s home” notification on the living room Xfinity box if the TV is on.

IFTTT isn’t expecting the average user to create these scenarios on their own, or even download the IFTTT app. Instead, users can browse through relevant Applets in the existing Garageio and BMW apps, and activate the ones they want with an on-off switch.

“For end users, we want to make it simpler. For developers, we want to make it more and more powerful,” Tibbets says.

Where does that leave power users? They can still create and share basic “if this, then that” scenarios, and IFTTT is working on a “Maker” program for those who want to build more complex Applets. But essentially, Tibbets says, IFTTT has “flipped the audience.” Internet device and service makers are now IFTTT’s primary customers, taking advantage of the work that IFTTT’s most active users are doing.

“We really see partners as the people that can make that connection with what those power users are doing, and then bring that into their own products, and present that to a much broader audience,” Tibbets says.

For IFTTT’s investors, the launch of the partner program is a pivotal moment.

“This is the key point at which the company shifts to a true business model, and a new level of scalability and access,” says Josh Goldman, a partner at Norwest Ventures, which led IFTTT’s Series B round. “This is something we’ve watched and planned for for a long time, and I think it’s going to be enormous.”

Who Pays For The Pipes?

To date, more than 300 services connect with IFTTT, though it’s unclear how many are paying to do so. Before the partner program launched, IFTTT had built many integrations on its own at no charge to those services, because the relationship was symbiotic. (Since launching the partner program, the company says “the majority” of its services are paying customers.)

George Yianni, head of connected lighting technology for Philips Lighting, says that roughly one quarter of Philips Hue owners have connected their light bulbs to IFTTT, and he’s been “absolutely blown away” by what they’re created. (Among his favorite recipes: Changing the color of hallway lights when it’s going to rain, and flashing the color of the user’s favorite sports team after a scoring play.)

“A major thing that attracted us towards it was the almost unlimited scope it enabled for our consumers to do the things that they were demanding our products could do,” Yianni says.

Still, Yianni won’t say whether Philips would pay to join the partner program. For now, IFTTT has brought Philips onto to the Applets platform as a “long-time partner of IFTTT,” but not as a paying customer. Philips is still exploring how to proceed from here.

“I’m not really sure how that process will go,” Yianni says. “We’ve had a long, very successful partnership with IFTTT, where we’ve both gotten a lot of value and publicity out of it, so we’ll just have to discuss with them to see how best we do that going forward.”

August Home, a maker of smart door locks and doorbell cameras, was similarly non-committal about paying. Nate Williams, August’s chief revenue officer, would not comment on how the company might use Applets, and instead talked about the value of IFTTT’s community.

“IFTTT users and their community are some of the most passionate advocates for smart homes, and they’ve given great feedback regarding additional features they’d like to see and functionality, so for us we think it’s been a winning combination,” Williams says.

Other companies are more enthusiastic. Jamie Siminoff, CEO of smart doorbell maker Ring, recently told Fast Company that paying IFTTT for its integration powers was far more cost effective than building them on its own.

“They basically save us a million dollars a year in engineering that we’d have to do in order to maintain this type of flexibility of products for our customers,” Siminoff said.

IFTTT, for its part, says it’s seeing plenty of demand. “Our partners were constantly asking for a way to get their services on IFTTT quickly and easily,” Tibbets says. “The value of one connection leading to hundreds of integrations was clear—at one point we had a waitlist of 4,000 partners.”

The Access Company

Getting companies to pay up isn’t the only challenge ahead for IFFFT.

Even as IFTTT has solved one issue of balance—that of mainstream versus power users—it must now figure out how to manage the sometimes-opposing interests of connected services and their customers.

As an example, Philips Hue is the only connected light bulb that works with BMW’s “Warm Welcome Home” Applet. Rather than exclude other lighting brands like LIFT, Lutron Caseta, and Belkin WeMo, it might make more sense to define connected lighting as a generic concept, so that a single Applet can connect with any smart lighting solution.

Still, Tibbets is wary of defining the limits of what a particular device can do—for instance, ignoring the possibility of lightbulbs with embedded speakers—and as Norwest’s Josh Goldman suggests, a generic approach would risk alienating IFTTT’s partners.

“I don’t like to invest in services that turn consumer brands into plumbing,” Goldman says. “If they obscure the brand, then it kind of takes value away from partners. They want to be branded in the consumer’s mind.”

Beyond balancing those interests, IFTTT will need to remain a neutral party for all of its partners, not putting its thumb on the scale for any one company or steering people into any one particular ecosystem. There’s always a risk that IFTTT could abuse its power as it scales up—or gets acquired. (Tibbets doesn’t rule out the possibility of acquisition by the right company, though he says the goal is to build a large, standalone business.)

But right now, as always, IFTTT is taking its time to figure all those things out. The startup has spent six years defining itself, and has deep-pocketed investors who believe in Tibbets’s methodical approach. With a business plan in place, now it’s up to IFTTT to insert itself between as many vital internet services as it can—and convince them that those connections are worth paying for.

“We think the long-term opportunity is just massive,” Tibbets says, “and you’ve got to be patient to tap into it.”

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(38)