Kickstarter Wants To Help Gadget Crowdfunders Keep Their Promises

Well over a year ago, I backed a Kickstarter campaign for a clever gizmo intended to make an iPhone look and work more like a point-and-shoot camera. I pledged $100 and took note of the fact that its creators planned to ship their invention in November 2016. Then they reported that they had run into manufacturing issues once the device went into production. They pushed their ship date from November to January. Which turned into April. And then, last week, I got an email notification that my reward was finally on its way.

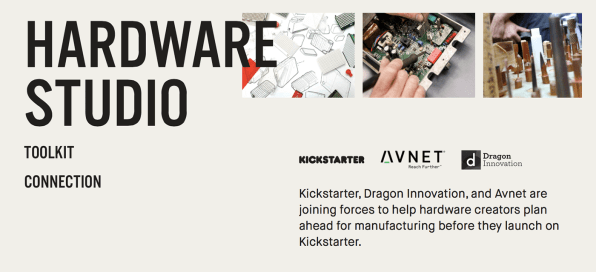

The timing was uncanny: When that notification slid onto my screen, I was on the phone with Scott Miller, the CEO of a Boston-based company called Dragon Innovation. Dragon helps companies deal with the infinitely complex challenge of turning ideas into products that can be manufactured within the constraints of a particular budget and timetable. And it’s part of an upcoming program from Kickstarter called Hardware Studio. Launching in September, it’s designed to help the the creators of hardware campaigns bring their projects to life with a minimum of surprises. Along with Dragon, Avnet–an enormous distributor of electronic components–is teaming with Kickstarter on the effort. (Kickstarter arch-rival Indiegogo already has similar partnerships with Riverwood Solutions and Arrow Electronics.)

When products funded on Kickstarter run into problems, it’s often because of lack of planning–and planning is especially tough to do for the sort of small grassroots teams responsible for many crowdfunding campaigns, who are often trying to accomplish something they’ve never done before. The good news is that this is a solvable problem, especially if such a team can map out a plan in consultation with experts who have deep knowledge of how to bring products to market on time and within budget.

“The whole trick is doing all of this work up front,” says Miller, who spent years in China working on manufacturing issues for iRobot, creator of the Roomba. “Once the campaign launches, it’s an incredibly busy time, and once it closes you have a commitment to doing what you said you’re going to do.”

“We’re really providing [creators] support before they launch,” adds Julio Terra, Kickstarter’s director of design and technology. “So when they click ‘Start,’ their rewards are properly priced, and they have a really clear understanding of all the steps required to bring projects to fruition and the schedules associated with that.”

Rise Of The Crowdfunded Gadget

When Kickstarter launched in 2009, the initial goal was to help artists such as musicians get up-front funding for ambitious creations. It soon turned out that the crowdfunding model was applicable to gadgets, too: According to Kickstarter lore, the moment that made that clear was a 2010 campaign for the Glif, a smartphone kickstand/tripod adapter. Within a couple of years, ambitious consumer-electronics products such as Pebble’s smartwatch were raising millions on the site. They still do, to the tune of $1 billion in total funding over the years for tech and design projects.

Failing to meet original schedules is so common for hardware projects that I’ve never paid much attention to the dates associated with campaigns I’ve backed, choosing to instead think of my rewards as happy surprises. Along with deadline trouble, campaigns sometimes suffer from budgeting woes. And worst-case scenario, that sort of bungled planning leads to meltdowns such as the Coolest Cooler, which raised more than $13 million on Kickstarter in 2014 and says it still can’t afford to send out coolers to all the campaign backers who pledged enough money to get one.

All along, Kickstarter has not been comfy with the notion that anyone might mistake the site for a gadget store. (In case anyone was unsure on that point, its founders titled a 2012 blog post “Kickstarter is Not a Store.”) But the company is trying to steer hardware and design campaigns in a direction that keeps Kickstarter feeling like Kickstarter and leaves campaign backers happy they put up their money, without being too heavy-handed about it. Hardware Studio is following Request for Projects, another new effort, launched last month, that encourages hardware and design campaigns to focus on unique, creative projects rather than me-too stuff.

Hardware Studio will offer two tiers of assistance for creators in the early stages of readying a campaign. For starters, anyone who’s putting together a campaign will be able to participate in Hardware Studio Toolkit, a community site with webinars, tutorials, and other resources put together by Dragon, Avnet, Kickstarter, and veteran creators.

A higher level of service, Hardware Studio Connection, will offer personalized “office hours” advice from Dragon and Avnet staffers, plus discounts on components. Participants will also get access to a Dragon online tool called Product Planner that helps hardware companies budget time and money. Kickstarter may also provide extra promotional attention to campaigns spawned from Hardware Studio Connection once they’ve launched.

Creators must apply to get into Hardware Studio Connection, and Kickstarter will let Dragon and Avnet choose who makes the cut. “It needs to be a project that is complex enough electronically,” says Terra. “Beyond complexity, they need to have a certain level of ambition.” To qualify, products will need to have progressed well beyond the raw conceptual stage by the time they become a Kickstarter campaign.

The sort of assistance that can come out of Hardware Studio will start with fundamentals such as identifying the components needed to create a product; determining the cost of acquiring them all; and tallying a total so that you know how much you’ll need to crowdfund. And it will range up to big decisions such as figuring out where to go for manufacturing–which is most typically done in China, although small batches can effectively be produced in the U.S., according to Miller. “Finding the right factory is almost like finding the right spouse,” he says. “If it’s done right, you’re going to have a very long partnership.” (Dragon has worked with many Kickstarter campaigns on such matters, including Pebble–which, even though it eventually sold itself for parts to Fitbit, was one of crowdfunding’s biggest success stories with more than 2 million smartwatches sold.)

If Hardware Studio can help campaigns run more predictably, its benefits for creators, backers, and Kickstarter itself are obvious. For Kickstarter’s two partners, the initiative offers the potential to establish relationships with crowdfunders who might become thriving businesses interested in paying for Avnet’s parts and Dragon’s help on an ongoing basis.

“This gives Avnet and Dragon access to this amazing pool of startups from a leads and pipeline standpoint,” says Terra. “It’s an amazing opportunity.”

Some people with nifty ideas are unprepared to bring them to market on time and within budget. But a little advice from experts might make a big difference.

Well over a year ago, I backed a Kickstarter campaign for a clever gizmo intended to make an iPhone look and work more like a point-and-shoot camera. I pledged $ 100 and took note of the fact that its creators planned to ship their invention in November 2016. Then they reported that they had run into manufacturing issues once the device went into production. They pushed their ship date from November to January. Which turned into April. And then, last week, I got an email notification that my reward was finally on its way.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(34)