Moog Let Its Engineers Spend 10 Months On An Art Project

When Yuri Suzuki approached Moog Music with his latest idea, the company immediately said yes. It’s not like the 62-person synthesizer manufacturer, nestled in the mountains of Asheville, North Carolina, had nothing better to do. Moog’s tiny team of engineers is always busy churning out products, from guitar effects pedals to modular synthesizers that cost a small fortune. And this project was different: Unlike everything else built in Moog’s factory, this device wouldn’t be for sale.

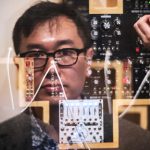

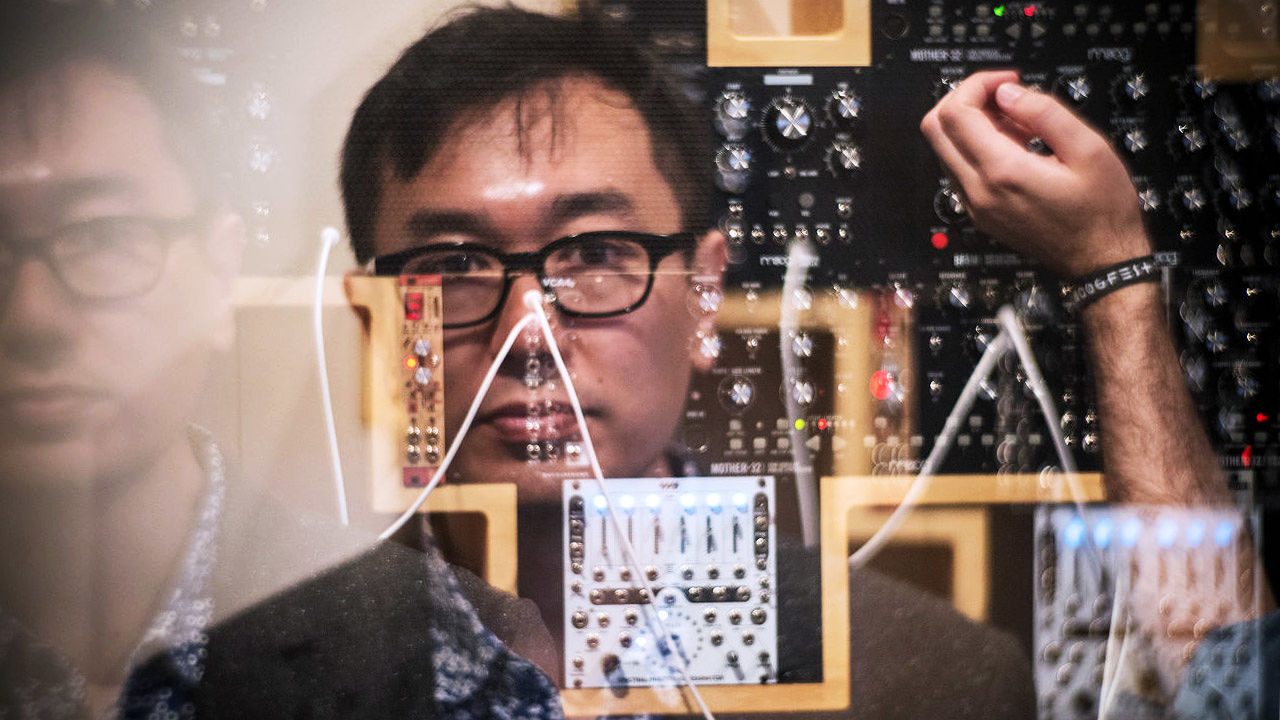

At a meeting with Moog in mid-2014, Suzuki, a Tokyo-born artist known for his work at the intersection of sound, music, and technology, proposed his most ambitious installation yet. The Global Modular Synthesizer is a wall-sized synthesizer designed to be approached and fiddled with by whomever may encounter it. As warped as they can sound (depending on how much fiddling one does), the noises emanating from the machine are actually crowdsourced audio samples: sounds recorded by everyday people all over the world and submitted to Moog for the project.

“The process for making sound is quite unique in a modular synthesizer,” says Suzuki, who says he’s been dreaming of owning a Moog synthesizer since he was a teenager. “There’s something fascinating about the cables and connecting different sounds.”

The elaborate system of knobs, sliders, blinking lights, and patch cables will look inviting to anyone familiar with the musical niche of modular synthesis—the method of creating layered, futuristic soundscapes and electronic music first pioneered by the likes of Moog founder Bob Moog in the late 1960s—but it also invites novices. Its design, large in size and outward-facing, begs for participation. That isn’t to say that the device is simple to use—to the layperson, its interface looks like it could be used to launch a small spacecraft—but by simply futzing around, the average person can begin to hear how various oscillators, filters, and effects can be used to manipulate sound.

And unlike a regular modular synth, this one takes on a universally familiar shape: Its pieces form a map of the world, with each field-recorded sample sound mapped roughly to its proper geographic location. That includes everything from Latin American street music and Eastern European birds to gongs in Laos and a marriage ceremony in India. A researcher even captured and submitted the sound of seals communicating under a sheet of ice in Antarctica.

“I’m interested in sounds around the world because I’m used to traveling a lot,” says Suzuki. “I was thinking about a peaceful way of connecting country to country.”

The idea is an extension of an earlier project called The Sound of the Earth, in which Suzuki made a three dimensional, globe-shaped vinyl record that played sounds he recorded in various locations around the world. For the Global Modular Synthesizer, Suzuki created a set of three-dimensional CAD designs and then handed them off to Moog engineers.

“Engineering-wise, the hardest part was just picking a platform,” says Chris Howe, the Moog engineer who led the technical development of the project. “Coming up with the exact processor that we wanted to use, not going too overboard, not going too light. Ensuring we have something that sounds good and can do interesting things.”

About two months into the project, the idea of adding a special reverb effect came up. But instead of recycling a prebuilt reverb module from an existing synth, Howe and his team decided to use field-recorded sounds to produce it. A recording of hands clapping inside a cave, for instance, could be used as a sort of sonic template for adding a similar echo to whatever sounds happen to pass through the new machine.

“You can make it sound good, but depending on where your settings are, you can just make it sound like gnarly garbage,” says Howe of the custom reverb effect. Such is the nature of modular synthesis: The sounds it generates vary widely from the beautiful to the abrasive, depending on countless parameters set by the composer.

Miraculously, last-minute design changes like this didn’t complicate their already nerve-rackingly tight production time line, even if Howe and his colleagues were still screwing the front panel onto the Global Modular Synth the morning of the day it was set to debut at the Moogfest music and technology festival in Durham, North Carolina, in late May.

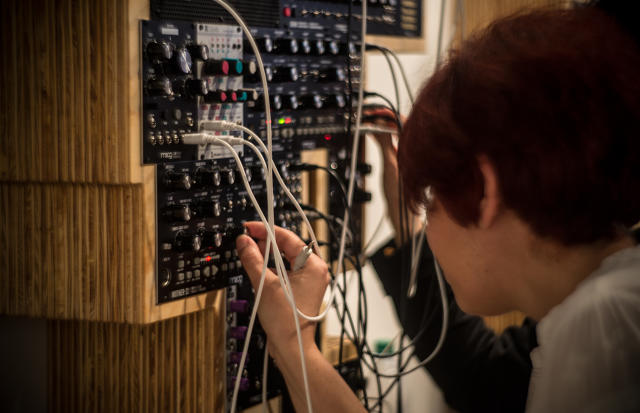

Throughout the festival, the modular synth proved popular. Attached to the wall of the Moog Pop-Up Factory and synth shop in Durham’s historic tobacco district, the installation attracted a thick and curious swarm of visitors throughout the four-day festival. But why build such an elaborate, undoubtedly expensive machine for a four-day installation?

For one thing, it’s useful R&D.

“For us, this was a fun project, because it was almost entirely new solutions,” says Howe. “We’re traditionally an analog synth company. We don’t do digital effects.”

You might think a project like this—one that involves so many synthesizer modules of the sort that Moog builds every day—would be a conglomeration of recycling parts. It is quite the opposite: This thing is a fresh build, and, if anything, the technical hurdles overcome during its creation will find their way into future Moog products.

There is also the branding and PR effect. An installation this creative and technically ambitious can, for instance, easily grab the attention of a Fast Company writer. But beyond press coverage and the on-the-ground impact of the Global Modular Synthesizer, Suzuki and the Moog team hope to find it a home in a museum or perhaps take it on tour to various cities. Suzuki’s work has appeared in New York’s Museum of Modern Art in the past, so its inclusion there wouldn’t be a stretch.

For now, the Moog team is focused on unpacking their new creation in Asheville while its future home is being determined. Oh and don’t worry: Before he flew back to his home in London after Moogfest, Suzuki finally made good on his boyhood fantasy and bought himself a classic Minimoog tabletop synth. It’s no wall-sized modular system, but it’ll do for now.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(48)