Native Advertising Is Broken. Here’s How To Fix It

In 2016, just 32% of Americans trust the mainstream media—down 8% since last year. By comparison, 78% trust the technology industry. Heck, even 51% of people trust the financial industry.

These existing trust issues contributed to the media industry’s latest crisis: the spread of fake news across Facebook, which likely influenced the election. A BuzzFeed report found that the top 20 fake news stories about the election were shared 1.4 million times more than the top 20 real news stories. When Americans don’t trust verified news sources, they’re more likely to believe the “reports” pushed out by fake news sites.

Amid this controversy, it’s hard not to wonder about the ramifications of native advertising. For the past few years, media critics like Jeff Jarvis and Andrew Sullivan have worried that native ads, which resemble editorial content but are actually sponsored by brands, confuse readers and erode trust in publishers.

As it turns out, they do.

This fall, my team at Contently partnered with the Tow-Knight Center for Entrepreneurial Journalism at CUNY to conduct an in-depth study of how consumers interpret native advertising. Through focus group studies and a survey of 1,212 adults who regularly access the internet, we found:

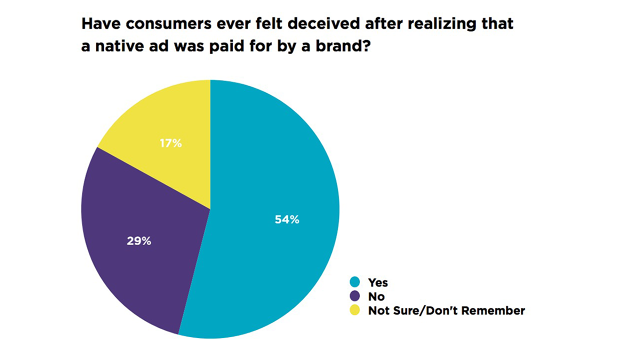

Most people (54%) have felt deceived by native advertising in the past.

- The vast majority (77%) did not interpret native ads as advertising.

- Almost half (44%) were not able to correctly identify the sponsor of the native ad they read.

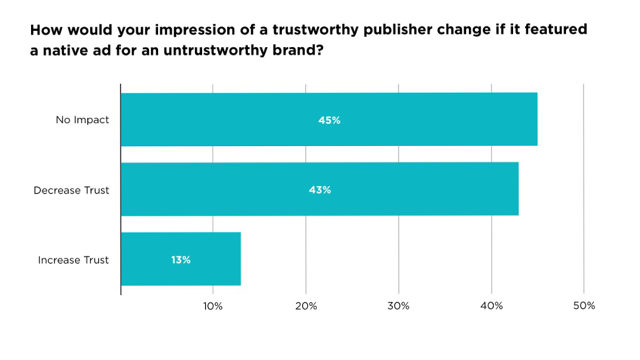

- A similar number (43%) lose trust in a publisher when it features native advertising from an untrustworthy brand.

Given that reader trust is a scarce commodity for media companies right now, both digital publishers and the FTC need to fix this problem. Our study revealed some promising solutions that could help.

Create A True Standard For Native Ad Labels

Last December, the FTC released long-anticipated guidelines for native advertising. The incredibly confusing document provides 17 different examples of how and when to disclose native advertising, many of which seem to contradict each other and the FTC’s overarching recommendations. Example 2, for instance, seems to state that if a native ad for a brand isn’t explicitly promoting a product, it doesn’t have to be labeled at all as an advertising. That’s insane. If a brand is paying for a piece of advertising to be produced, it needs to be labeled as such.

Given these ambiguities, it’s not surprising that 70% of publishers aren’t compliant with the FTC’s labeling guidelines, according to a MediaRadar analysis. Just 23% of consumers in our study correctly identified native ads as advertising (the rest thought it was editorial content or a hybrid of advertising and editorial content).

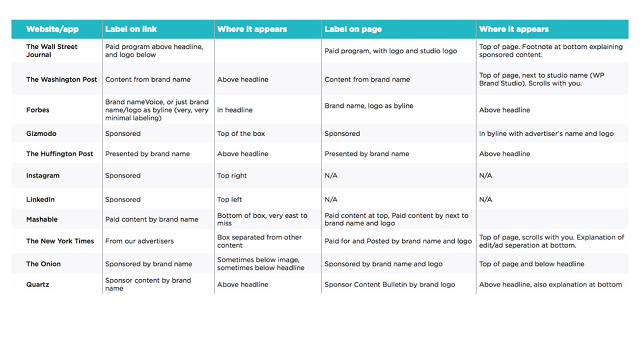

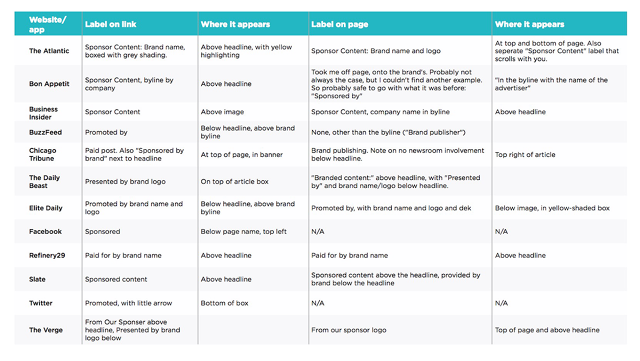

There’s one simple way to fix this: adopt a standard label for native advertising. Currently, major publishers rely on a confusing array of terms. In some cases, a single publisher uses three or four different labels on the same site. It’s ridiculous to expect consumers to keep up.

In its guidelines, the FTC pushes “advertising” as the standard label publishers should adopt. Yet publishers uniformly reject doing so, perceiving native differently than display.

“A great display ad will divert people’s attention from what they sought out to do,” Mike Dyer, president of The Daily Beast (which uses the label “Sponsored Content”), told Adweek. “Content is the thing people are seeking out. It is the end of the behavior chain.”

“Nuances and labeling aside, we offer marketing solutions for brands,” said Stephane Krzywoglowy, director of ad product at BuzzFeed. “We embrace the fact that a variety of advertising exists and know that even within the ‘native’ category, it takes a variety of forms.”

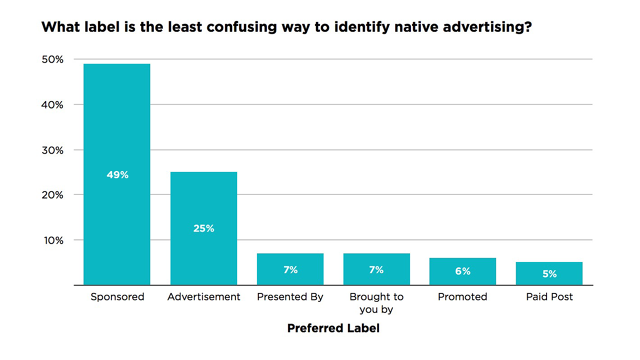

However, there is an alternate label for native advertising that consumers prefer and publishers would accept: “Sponsored.” In our study, 49% of respondents said that “Sponsored” was the least confusing label for native advertising. “Advertising,” at 25%, was second.

Many sites have already adopted the “Sponsored” label, including Facebook, the world’s largest distributor of native advertising. A single standard enforced across the industry would help consumers identify native advertising and make smart choices about the content they choose to consume. The FTC needs to work with publishers to simplify guidelines and make this happen.

Only Partner With Trustworthy Brands

For publishers, native advertising is a high-risk game. If they partner with untrustworthy brands, they could lose a large chunk of their audience. As noted above, when a trusted publisher features native advertising for an untrustworthy brand, 43% of consumers lose trust in that publisher.

But when a trusted publisher partners with a trusted brand, the opposite occurs: 41% of readers trust the publisher even more.

“I feel like [publishers] need to be selective in what they put on their sites and who they allow to, I guess, buy into their sites,” said Sara, a 29-year-old focus group respondent. “You want something reputable or it will take away from the credibility of the site.”

Relatedly, a 2014 study on native advertising by Edelman and the Interactive Advertising Bureau found that “brand relevance, authority, and trust were the most important factors to driving consumer interest in in-feed sponsored content across all media verticals.”

In other words, publishers shouldn’t make native-ad deals with unreliable brands, no matter the short-term financial gain. The long-term erosion of trust is just too hazardous.

Don’t Waste Time Blaming Facebook

Facebook has rightfully faced tons of criticism in recent months, both for its reluctance to police fake news and for its algorithm’s tendency to serve content that reinforces users’ pre-existing beliefs.

But it isn’t just a place where fake news spreads. Publishers like BuzzFeed spend millions of dollars every month to distribute native advertising on Facebook since it has the most powerful combination of targeting and cost efficiency of all the paid-distribution platforms. Could native ads confuse consumers just as much as fake news?

Our study found that wasn’t the case. When consumers were first exposed to a native ad via a Sponsored Post in a Facebook feed, 73% identified it as advertising before they clicked through—likely because they’re used to seeing advertising units in their Facebook feed and the “sponsored” label that accompanies it.

There’s been a lot of talk since the election about how the media lives in a political echo chamber. This applies to how we think about native advertising as well—the way publishers label native advertising may seem transparent to a trained media professional, but it’s just plain confusing to most people. We need simple guidelines, uniform labels that everyone uses, and more visual markers to distinguish native advertising from editorial content. (Seventy-four percent of respondents said that native ads should include both the brand name and logo and have a dedicated place where they appear on publisher sites.)

Right now, consumers trust the media industry far less than they do the bankers who caused the greatest economic disaster in a century. If publishers want to regain trust, they can’t continue to show people content that seems designed to trick them.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(16)