This Teenage IBM Employee Got His Job By Buying An Old Mainframe Computer

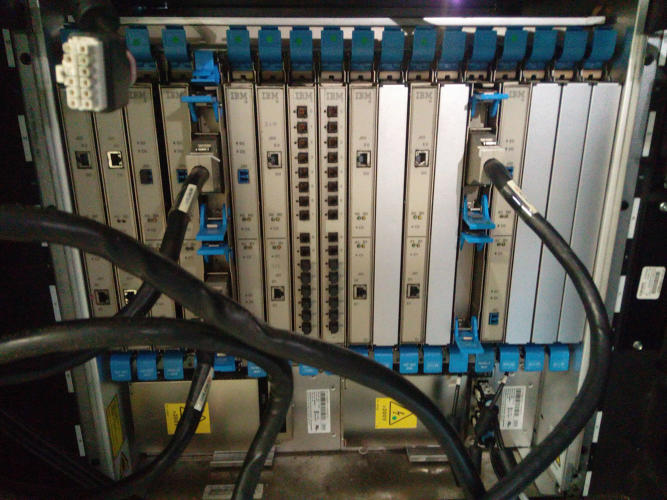

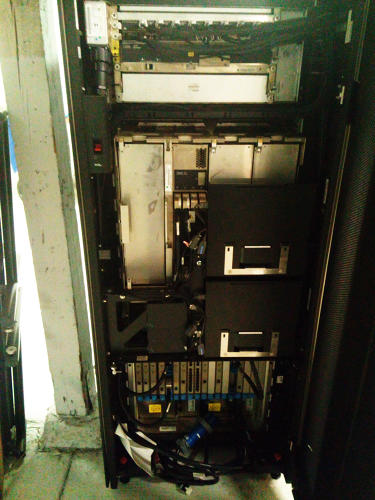

The IBM z890 Mainframe computer weighs 1,500 pounds and stands over five feet tall. When it was first unveiled in 2004, it cost over $300,000. At that time, the z890 was a cutting-edge solution that helped midsized enterprises run their businesses. A 2004 ComputerWorld article described it as small, but by today’s standards it’s a big honking computer, and it’s for anything but personal use.

That didn’t stop 19-year-old Connor Krukosky from buying one last year. He always had an interest in the behemoth machines, and this slowly but surely turned into a passion that led to installing a computer the size of a small person in his parents’ basement.

In an age when enterprising young people are landing jobs via Snapchat or Twitter, Krukosky’s antiquated computer would be responsible for earning him a gig at IBM before he was even enrolled in college.

Let’s back up a bit to understand the full story. Krukosky’s parents have always encouraged their son’s interest. They gave him his first computer—an IBM Aptiva—when he was 18 months old. Of course, it’s unclear how he actually found use of a computer then, but I guess his point was that his family introduced him to computers at an early age.

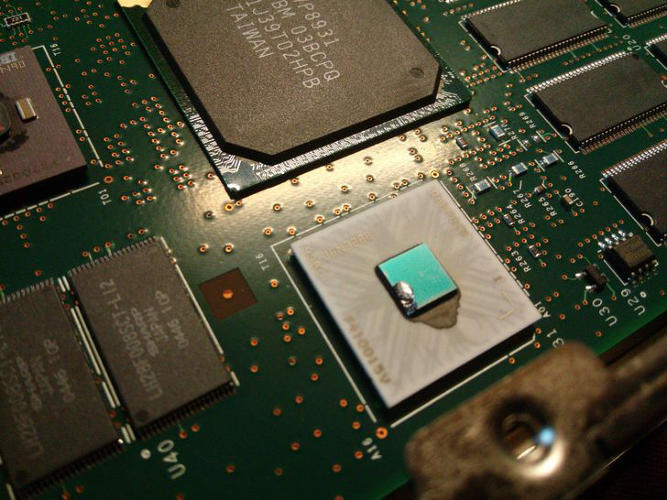

Besides just using them, Krukosky also enjoys taking computers apart. For years he did just this: Tinker with old machines and peek into their insides to try and figure out what precisely they did. Eventually, deconstructing these computers wasn’t enough. Krukosky began to fix them too, learning about old operating systems like DOS along the way.

In his early teen years, he said he became “more curious about [those] little chips inside.” This morphed into a fascination with how computer wiring evolved over time as he learned about the ways they were originally built. Doing this, he came across an online community of people who collect antiquated machines.

Getting The Mainframe

After collecting more than a few older machines, he began to research mainframes. “I thought it was interesting,” he told me. “I knew about mainframes and the history of IBMs.” He never really considered the prospect of actually buying one, until one day (when he was 18) he came across a listing for one. Usually, he explained, these listings are in California. But this one happened to be for sale two hours from his home in Maryland.

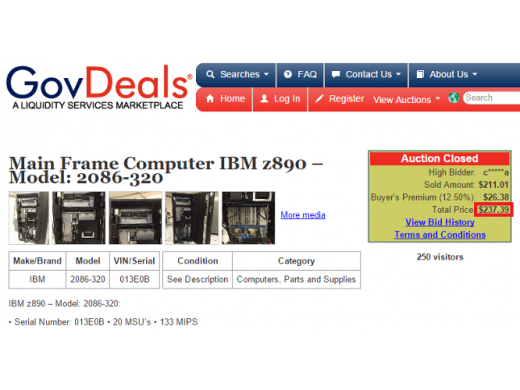

Krukosky and his father drove to Rutgers University in New Jersey, where the mainframe was being auctioned off. They paid $237 for the beast.

Because it was more than a decade old, no longer owned by IBM, and therefore, no longer under warranty, Krukosky and his father were able to deconstruct the machine to transport it. Rutgers employees watched them slowly put it piece by piece in a car.

If it had been protected by a warranty, transporting the mainframe would have been a difficult task, since IBM does not allow for these machines to be taken apart. Instead, working mainframes must be transported in one piece via large and expensive vehicles.

Turning The Beast On

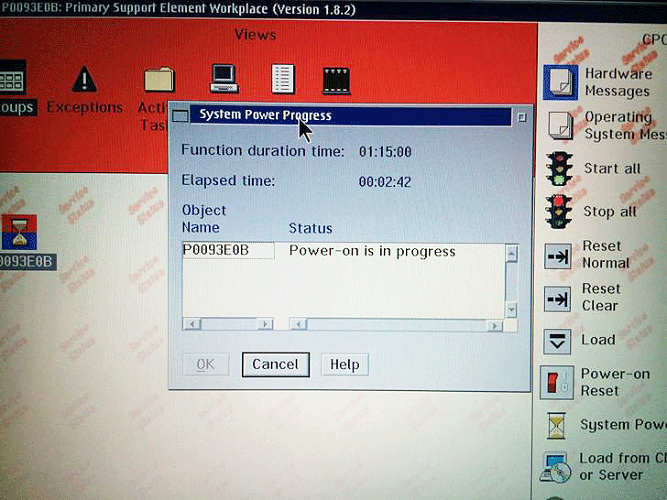

The two were able to haul the nearly-one-ton machine and put it in the family basement. Krukosky reassembled the machine there and slowly tried to figure out what to do with it. The first problem was actually getting the machine to turn on. “I didn’t know how to effectively boot the machine,” he told me. “It’s a long and tedious process . . . it’s not just flipping a switch.” He consulted with his friends online and, after a series of trial and error, finally figured out the proper way to get the mainframe to light up.

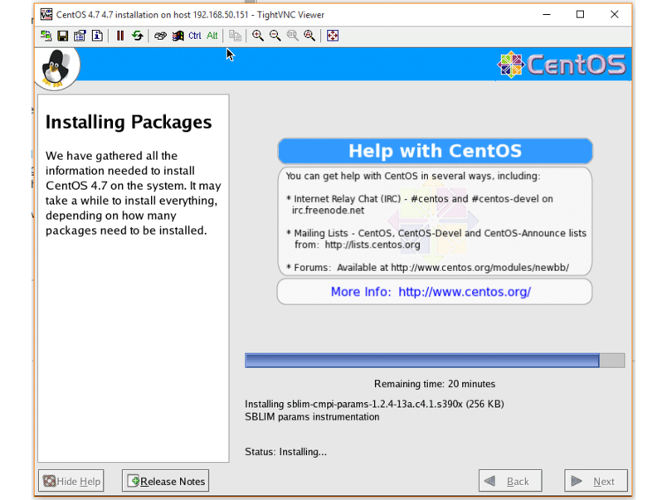

Once it was working, he tinkered with the platform. The machine was running Linux and Krukosky used it, as he said, “to move data.” That is, a mainframe’s purpose is to run an entire internal network so that people—usually in businesses—can share information with each other. It’s a necessary function that a lot of computer users take for granted.

Doing this gave Krukosky the chance to see exactly how machines provide the connectivity we all expect in our daily lives. A lot of what he did with the z890 allowed him to learn how to run such a network. He spent hours in his basement looking at the screen connected to the mainframe, inputting code to build his own internal network and running the machine continuously for 30 days.

I asked him what he did every day for a month, and he said “exploring it, playing around with it.” He and his old computer friends played around with some applications that were on the platform, and even made an FTP server that put some data on the internet. “It wasn’t anything serious,” he said.

What was serious, though, was the energy bill. Running a bulky computing-heavy machine is not cheap—especially one that is designed to never turn off. After only a month of computer fun, Krukosky’s family saw an energy-bill increase of over $200. His parents paid to power the expensive setup in order to encourage their son’s love of machines.

Landing A Job

Krukosky decided to turn the machine off after first the month was up. During that time of experimenting and connecting with fellow mainframe enthusiasts, Krukosky continually posted inquiries online. One was on an IBM-specific email list where people discuss their technical experiences with mainframes. Said Krukosky, he emailed the people on this list just to “see what their reactions were.”

Some were impressed by the then 18-year-old and gave him some helpful information about the machine. One person even invited him to speak at a conference in San Antonio. Krukosky’s presentation: “I Just Bought an IBM z890—Now What?” was given to a group of enterprise computer pros, introducing him to a whole new network. This initial interaction led to a “formal” connection when “some people from IBM came to me and said hi,” Krukosky recalls.

After some discussion, the company invited Krukosky to visit its offices in Poughkeepsie, New York. The meeting was just a tour of the company’s grounds, however, it also got him talking with the company about employment. Though he was taking some community college classes, he wasn’t fully enrolled in a university. IBM thought this was a perfect time to work with the young mind.

Since last summer, Krukosky has been working for the company and learning about a variety of IBM’s backend projects. “It’s not really an internship,” he told me, as he’s being paid to work for the entire year, is not enrolled in school, and is helping out at numerous departments. Right now he’s working in the memory lab researching “how the current mainframe supports terabytes worth of memory.”

Krukosky told me his future plans aren’t set. He still needs to go to college, most likely Marist College in Poughkeepsie, so he can continue to live and work near IBM. The plan right now is to work part-time at IBM while enrolled, and then figure it out from there. He added that he’ll probably get a dual major (possibly engineering and another computer-focused subject), but sees himself focusing on computer science down the line. (Neither IBM nor Krukosky went into detail about formal plans after college.)

Krukosky also wants the ability to show off his collection of computers, and perhaps even open a museum. He rattled off a list of all the old IBM machines he owns—starting with one of the old punch-card computer systems—which roughly translates into a timeline of computer evolution.

He wants to have a space where people can “play with things,” he said, because that’s really what he likes to do: Play with computers. And I’m guessing that playfulness is going to continue to steer his career.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(162)