What The GOP Could Learn From Companies Facing Leadership Crises

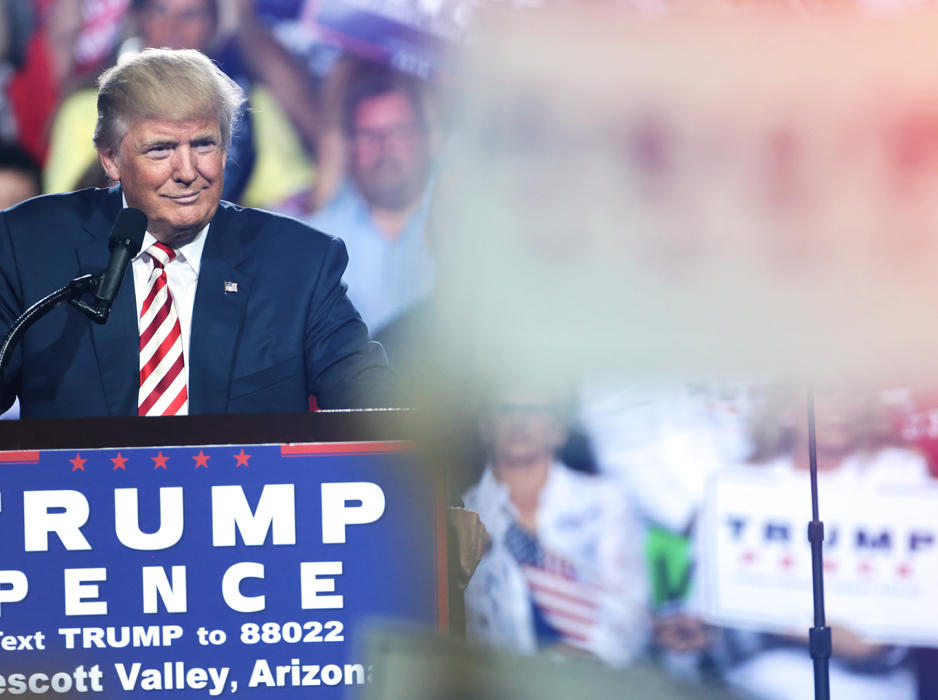

Since last Friday’s release of a leaked recording of Donald Trump boasting about his desire to grope a woman, the Republican Party has plunged into complete turmoil as party leaders debate what to do about their presidential nominee. As top members of the party drop their endorsements, others including congressional leaders like House Majority Leader Paul Ryan, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, Marco Rubio, and Ted Cruz have denounced Trump’s words but hedge when asked whether or not they support him. In response, Trump and his army of supporters have lashed out at Ryan as the party descends further into civil war. And it threatens to get worse after last night’s revelations of multiple women claiming that they had been sexually assaulted by Trump.

It’s a complicated situation for the party, to say the least, as it faces the risk of losing congressional seats (and potentially its majority in the House of Representatives) and a brand that has been tarnished for years to come. And it’s a crisis that requires a great deal of strategy to properly maneuver. It’s also an issue that corporations—from multinationals to startups—have been known to face with varying degrees of success. An abrasive but popular CEO causes a public outcry, which prompts the board of directors and other insiders to cringe in horror and figure out how best to react for the future of the company.

Leadership breakdowns

The most recent example that comes to mind is Wells Fargo. The bank has been embroiled in one of the most high-profile banking scandals since the financial crisis, after news broke that the company had been systematically signing up customers for phony accounts. The company has agreed to pay a $185 million settlement and is now trying to rebuild trust from its customers. Initially, the board announced late last month that Wells Fargo’s CEO John Stumpf would stop receiving a salary, halt his 2016 bonus, as well as forfeit tens of millions of dollars worth of stock awards. But eventually, it decided that wasn’t enough punishment and he was forced to step down.

It was a clear message from the board that its response needed to be swift and definitive; Wells Fargo had to clean up its act. But one of the many problems in such scandals is that they stem from a rampant culture of systemic malfeasance and idleness. It wasn’t until the bank’s recent history of fraud made the headlines that the company fessed up and tried to fix it. But the way to turn things around is by both changing the course of action within the company as well as making it clear to the outside world that things are improving. And it’s necessary to have not only a company, but a leader, who embodies the principles of the entire organization. “The leader is so connected to the brand of the company,” says Elise Walton, an organizational and governance consultant.

Related: How Wells Fargo’s Work Culture May Have Cleared The Way For Scandal

Walton’s job is to help companies figure out organizational strategies that enable both boards and executive teams to work effectively together. “Now there’s a high expectation of board engagement, board effectiveness, board accomplishment,” she says. How the top brass works together dictates an organization’s success.

Google/Alphabet is facing a similar crisis. Its health sciences startup Verily has been in the news for the last year over allegations that the company’s head honcho has been impeding the company’s progress. Andrew Conrad, Verily’s CEO, was described in Stat News as “a divisive and impulsive leader whose practices are driving off top talent and leaving openings for competitors.” Despite this, Eric Schmidt has defended Conrad, saying at an Alphabet’s shareholder meeting that the parent company is “very, very confident of not only [Verily’s] approaches but also the controls, reviews, and processes that will ultimately produce some amazing medical breakthroughs.”

After initial reports surfaced of problems within the company, Conrad went on the offensive, allowing reporters to ask questions and see the company. According to Stat News:

After months of refusing to be interviewed by Stat, he reversed course—going so far as to greet a reporter at a Google building with a warm handshake and exuberant welcome, and act as personal escort to Verily’s adjacent headquarters. . . .

Dressed casually in a blue T-shirt, the CEO called his decision not to answer questions for Stat’s initial article “a catastrophic error in judgment”—because he had a good story to tell: Verily is hiring like mad from thousands of applicants who represent the “cream of the crop.”

For a leader with a tarnished reputation, this is a good strategy, say corporate consultants. “The first line of offense,” says Walton, is usually to address “the public aspect of it.” That is, make sure the optics are such that the company is making strides toward fixing the problem—or showing that no such problem exists.

The GOP crisis

Obviously, corporate crises differ greatly from political imbroglios, but some of these prescriptions still apply. Let’s take the current GOP predicament. The party, once a unified coalition, is deeply fissured. Trump was never the top choice of most career Republican lawmakers, and yet he won the party’s nomination. Nearly every elected GOP official backed and endorsed him, hoping that this would lead to more harmonious internal politics and a unified front against Hillary Clinton and the Democratic congressional candidates this election. But with Trump’s recent scandals, the party is at an impasse over what to do. They could either go against him, which would be a long-shot bet that he won’t win this election. Or they could fully back him. Instead, politicians like Ryan and Rubio are trying to manage an ever-more-precarious balancing act.

The problem with this strategy, says Walton, is that there’s too much uncertainty. If members of an organization are going to do something big, they have to make sure others on the inside are making the same move. If one Republican politician denounces Trump, the hope is that it will lead to many others following suit. So when organizations are in a time of crisis, it’s important that everyone is on the same page and acting in concert.

If you’re a leader, says Walton, you need to “make sure you have a team around you . . . no one person is going to be able to do it all.” If you don’t have a team helping weather a storm, you can “lose your voice and the credibility of your platform.”

No two situations are the same, but when there are tensions between organizational leadership, it’s important to have a clear vision. This, it seems, is what the GOP clearly lacks. If they put their money on Trump, it sends a message that they believe he is going to win big and want to maintain a modicum of good relations with the nominee. But if they go against him, they’re playing a long game of restoring the party once this election is over.

Instead, they’re doing neither. And if the Republican Party were a company, business would be floundering.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(30)