A Time-Management Master Plan For Your First 12 Months At A Startup

It’s week six in your new job at a bootstrapped startup, and the founder asks you, “Create a prototype of our software to share with investors. We don’t have a company name yet. And I need it in two days.” If this sounds familiar, chances are you’ve been an early employee at a startup. If this is your precise scenario, you’re Stacy La, Clover Health’s director of design.

When La first started with Clover Health, it was just the founders, head of product, and a data scientist. She was its first designer and the company hadn’t raised any money. Now she leads an eight-person design team, Clover is 500+ people-strong, and the startup has raised over $425 million. Though La was a seasoned design leader (Yammer, Microsoft) before Clover Health, it was her first time as a very early employee forged in the crucible of a fast-scaling company.

“When joining a later-stage company, your role and career path are more defined,” says La. “On the other hand, for a first employee in an area like engineering or design, you must, of course, focus on shipping your part of the product.” In her view, that means mapping out a timeline of key inflection points to guide your approach to developing the startup’s product, the team you’re helping to build, and your own career–all at the same time. Here’s how she did it over her first 12 months.

Your First Two Weeks

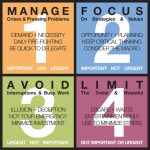

La recommends mapping out two-week themes for the first six months. Context-switching is a killer for everyone–especially for early employees who have to wear multiple hats. You have to be versatile, but focused, she says. “Early employees, like founders, must constantly operate at a balance of breadth and depth. I found the best unit of time to both efficiently execute and accrue a sufficient level of expertise on any key task was about two weeks,” says La.

“For example, when vetting design agencies, all my planning, research, meetings, evaluation, and decisions happened in a two-week span,” she explains. “Prioritizing biweekly themes creates enough momentum to create real value in a particular area of the business, but not so much as to cause a terrible setback if the intended results aren’t achieved.”

La stacked her priorities based on the constraints facing the business at the outset. “The nice thing about being there at the start is that your priorities are very clear, because the constraints are numerous and looming. The most pressing must be addressed or the others won’t matter because you’ll be out of business,” says La. “For example, we’re driven by CMS [Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services] deadlines. We had to be ready for open enrollment, which is October through December, and we had to have a brand and website. That needed to be in place before we could even think about hiring user researchers or developing a design system.”

She continues, “Two-week themes are flexible enough that I could swap them modularly as business needs changed, if needed–and compact enough that I was too busy to waste time thinking of opportunity cost once I decided to embark on one. Focus and flexibility made this approach work for my first six months.”

Your First Six Months

As Clover grew, La adopted a practice that her mentor, Airbnb’s head of design Alex Schleifer, calls “eyes on, hands on, horizon.”

“It’s a practical way to triage my time,” La explains. “‘Eyes on’ is work that I don’t need to do, but need to be informed about, such as designers’ progress on projects or design requests from the org. ‘Hands on’ are actions that I need to work on independently. That could be meeting with candidates or developing the design team’s OKRs, for example,” says La. “‘Horizon’ is a category of themes and developments that are a month to six months out. It’s about to get on our team’s radar, but not yet on mine.”

She explains how this works in practice: “Right now, that’s our design system, for example. This practice helps me get through to-dos and delegate. I do it on my own at the beginning of every week but at Airbnb Design’s scale, Alex does this exercise daily with a member of his staff. He emphasized to me that constant prioritization–the act of choosing to work on the right thing at the right time, over and over again–is the thing that will make or break a business. I’m now a lot more diligent about what I spend my time on, and the cost and ROI of those choices,” she says.

Splitting your time into these buckets creates processes, new ways that information flows through an organization. While this creates predictability, it can also fill up your calendar, La points out. “As the number of stakeholders increases, there’s a tendency to build in more process. So another great tip that Alex [Schleifer] gave me is: ‘Don’t add process unless it removes a meeting,” says La.

“That rule of thumb keeps you honest. When we started weekly design reviews, our goal was to give technology leadership visibility at key project milestones, and to push faster decision-making while shipping high-quality solutions. Adding design review into our design process eliminated 5+ individual context-sharing and sign-off meetings,” she explains.

Months Nine Through 12

Clover Health grew incredibly fast; in about two and half years its headcount went from five to 500. So starting after her six-month mark, La began shifting her focus from design work to growing a design team within nine months of joining. Not only was she creating what the product was to become, but also how it was going to be built.

“At about nine months, most my time was spent on recruiting and hiring, which was a shift out of my comfort zone. As an introvert, I noticed a change when the day held more coffee chats than independent work. When I wasn’t meeting people, I was drafting job descriptions, not just designing the product,” says La. “This isn’t atypical for any individual contributor who becomes a manager. However, as an early employee, a smooth transition at this moment is critical because it has a lasting effect on what the team will become–and often requires a founder’s attention. Kris [Gale, Clover Health’s cofounder] helped me realize that I was doing organizational design. I had to grow and structure a team that could get it all done.”

The key output in this time period is called “cathartic documentation,” La explains. “When a company grows that quickly after you’ve joined, you naturally get institutional knowledge that’s layers deep. Of course, this know-how shouldn’t be organized chronologically, but by utility. Luckily, an early employee has the built-in perspective to arrange this knowledge–and I’d argue the need, not just the ability,” says La.

“It was a release to get it all down and scale what I’d learned to the rest of the team,” she reflects. “This was, and continues to be, crucial for building out our team, onboarding new design hires, the design review process, and more. Growing quickly, I didn’t want the team to constantly reinvent the wheel.”

Documenting her design know-how gave La the bandwidth to help the company hire more intentionally. “When you have 15 people starting every week for three months you have to be extremely thoughtful about the hiring infrastructure you have in place. Communication gets exponentially complex and difficult as you grow, so we had to be conscious of who we were hiring and why,” says La.

“It took months of discussing and interviewing candidates, articulating our mission, and thinking about how we wanted to structure the team. At the beginning, I didn’t know how to pitch health insurance in a compelling way, and we didn’t have a product to show. What we did have is an awesome mission. I internalized our mission and the potential impact for design in the industry. In expressing it, I realized just how much I believed in what we were trying to accomplish,” she says. “After that it was easy to decipher which design candidates had similar beliefs and interests.”

But La knows it would’ve been a lot harder without cathartic documentation during this final period of her first year at Clover. “The demands of a startup are dizzying,” she says. “To anchor yourself, you must schedule time to write things down.”

A version of this article originally appeared on First Round Review. It is adapted with permission.

(21)