Are You Crowdsourcing Or Wasting Your Time?

A few years ago I joined a private Facebook group for writers and journalists. The payoffs were immediate: The members were professional and generous with advice, whether I was looking for editors’ email addresses or ideas for places to pitch stories. But what I also loved about the group was that it was a virtual watercooler, which was missing from my freelance life. I could now ask questions like, “How do you get out of the house but not spend a ton of money on coffee and scones?” or “Do you guys also feel irrationally sad after an editor gives you harsh feedback?”

At certain points I drifted from utilizing the group to just killing time in it. This reality didn’t hit me until the day I looked with frustration at a pile of unread books on my nightstand. “Just wondering when you guys find time to read for pleasure,” I started to write, and then stopped before I pressed “post.” This—this was the time I could be reading. Not the time writing the question and then checking back for that satisfying little red number in the top right corner of the screen that assures you people on Facebook are indeed interacting with you.

There comes a point where the convenience and helpfulness of crowdsourcing doubles back on its own productiveness. The most egregious example I ever saw was on a local parenting Facebook page I belonged to: “I need to go to the emergency room and was wondering which you guys recommend, Hospital A or Hospital B?” someone posted. Lots of people commented, but it took about 20 replies before someone finally said, “My suggestion is get off Facebook and go to the ER.”

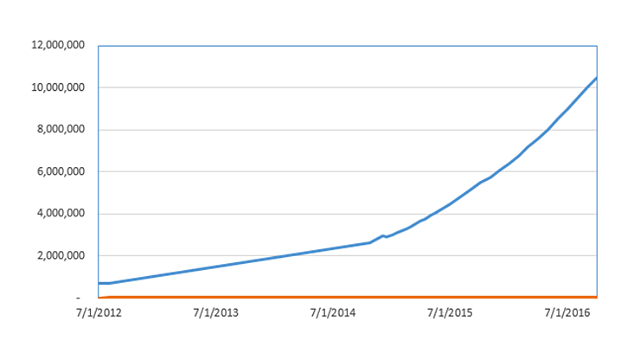

There are dozens of crowdsourcing platforms for any given field, with Facebook, Ask Metafilter, and Quora among its oldest and/or most well-known. Lior Zoref, author of Mindsharing: The Art of Crowdsourcing Everything, points to Quora’s numbers as a measure of the increased popularity of turning to a virtual crowd for professional or creative feedback. The number of people using it since its 2010 founding are growing exponentially. Over 10 million questions have been posed on the site as of October 2016, up from nearly 6.5 million in January.

When it comes to crowdsourcing, we have hundreds of sites to choose from, not to mention various ways to burn through time navigating each one. So what are some best practices for using crowdsourcing to its full potential versus wasting time online?

Get The Lay Of The Land And Make A Good Impression

The world of freelance writing is one where the breadth and number of professional communities has exploded—information that writers used to have to pay a fee to access (like editors’ contact information and pay rates listed through Mediabistro’s AvantGuild memberships) is now freely exchanged in Facebook writers’ groups. Rebecca L. Weber is a South Africa –based freelance writer whose work has appeared in the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. She belongs to several virtual groups for freelance journalists. She takes care to take the time to get to know a group before participating. “Usually when I join a new group, I introduce myself and read the posts for a little while before I come in with a question,” she says.

You want to avoid asking something off-topic or off-tone, despite this age of oversharing. It’s just not wise to share your professional weaknesses with a bunch of strangers. Weber says she asks herself, “Do I feel like exposing myself or sharing some semi-confidential information with these people?” Because, as she points out, nothing is ever really confidential. You might vent over a client, only to find out that they (or a friend) are lurking.

Additionally, you want to make sure that this seems like the place where your questions will actually be answered appropriately. Because it takes time to write a well-crafted question, you want to make sure it will be answered intelligently. Finally, Weber thinks it’s good practice to give before you get in order to demonstrate that you’re not just an information leech. “I try and comment on other people’s questions and needs first before coming in and asking for things,” she says.

Ask A Question Well

Make sure that the questions you ask are quality ones. “The leadership skill that we’re seeing a significant drop in is the skill of asking well-defined questions,” says productivity coach Jason Womack. One trick is to frame your questions so that they’re identifiable to the group at large. I wanted to ask my writers’ group the protocol for repurposing material for a story I had written that was killed. “I would phrase that not just as something that happened to you but a general question,” says Zoref. Instead of saying, “This thing happened to me,” he says, it would be smarter to phrase it as “Has this ever happened to you?” That way I could learn from my colleagues’ actual experiences and not just get their hypothetical feedback.

Additionally, Zoref says, it’s smart to avoid manipulating people with the way you ask a question. If you’re crowdsourcing for travel, you’re more likely to get good information if you ask in a neutral way, like, “Does anybody have any suggestions for a restaurant for a great night out?” instead of, “I heard this restaurant is great—what do you think?” By leaving your questions more open-ended, Zoref says, you “don’t tell people exactly what you are expecting them to say.” Plus, doing so avoids setting up a thread that is less likely to devolve into useless arguments.

You Get What You Pay For

As opposed to asking in a private, controlled group (particularly one where there’s a membership fee), crowdsourcing in free groups (on Facebook in particular) opens you up to risk of bad information or even strife. I recall getting sucked into an argument over, of all things, Beyoncé, in my writers group. One woman took exception to a critique I had posted about the singer, and I felt like she misconstrued my post. My fingers hovered over the keyboard as I debated whether to earnestly clarify my stance or offer a snarky retort. Ultimately, I deleted my original comment, but on any other day I could have gotten sucked in and lost precious time.

“Understanding a person’s intended tone and feeling there’s judgment going on are big problems in any online community,” says Weber. Political and personal issues can quickly spiral and, if you’re in the mood to be distracted, pull you away from your intended task. “You need to be protective of yourself. If there’s bad blood, you don’t need to return to that space,” says Weber (even if you’re worried that someone will never really understand your true feelings about Lemonade).

Shama Hyder, author of Momentum: How to Propel Your Marketing and Transform Your Brand in the Digital Age, will sometimes circumvent off-topic replies in advance. “People on social [media] can be snarky or just want to have fun with something,” she says. When she wants an earnest answer, she’ll provide a gentle caveat along the lines of, “I’d love a clear-cut answer” at the end of her crowdsourced question. “Like, I am looking to switch universities in the middle of my degree. Can anyone speak to this who has personal experience? Please no higher-education-is-a-waste-type answers.”

While we often indulge in fun off-topic threads that follow serious questions, ultimately it’s an inefficient use of both our and our colleagues’ time. Womack warns against recognizing those who “don’t really want advice—they just want to be seen raising their hands,” or those who provide answers because they “want everyone to see how smart they are.” It’s best to treat these virtual consults the way we would if we consulted an actual in-person mentor. In those cases, when he’s asking experts for advice, Womack says, “We sit down, I will frame the question, why it’s important to me, and I’ll shut up.” Knowing when to close one’s mouth (or stop typing) is especially important on Facebook, where we are encouraged to respond and engage. Despite the urge to create conversations based on each answer, it is more efficient to resist the urge to engage with each respondent.

Facebook Is Still Facebook

Weber is more wary of Facebook groups than of paid, closed groups, because even if we think we’re just checking in on that group, Facebook has very carefully studied how to pull us in. While you might be on deadline on a particular day, the people in your crowdsourcing group may be bored and just feel like chatting, and there’s no way to separate the quick-hitters from the stay-awhilers.

“So many people have Facebook open on their computer a lot of the day, so the group notifications are popping up, even if they’re checking something else. I think as a result there can be a lot more people piling onto a single conversation, even when they don’t necessarily have something to say,” she says.

To combat this, Weber simply sets a timer for 15 minutes on her phone to prompt her to close out of Facebook, regardless of whether she’s caught up on everything in her groups. Ultimately, the art of staying focused on a crowdsourced question takes simple discipline. “It’s less about social media than it is about personal development,” says Hyder. “You have to walk away from things”—even if you get that FOMO feeling from knowing people might be taking part in a thread—without you!

Ultimately, Weber, like many of us who use online crowdsourcing, has benefited from crowdsourced feedback. Recently, she asked a Facebook professional group to help her choose between two logos for her website. “So many people voted or gave me ideas to tweak it, they ended up picking one I wouldn’t have chosen,” she says. Even at its time-sucking, nonstop-notification worst, crowdsourcing ultimately comes from a good place, says Weber. “I think there is a sense that once you’ve figured something out, you want to share it and pass it on.”

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(23)