Astranis’s MicroGEO is a high-flying new take on satellite broadband

This article is about one of the honorees of Fast Company’s Next Big Things in Tech awards for 2022. Read about all the winners here.

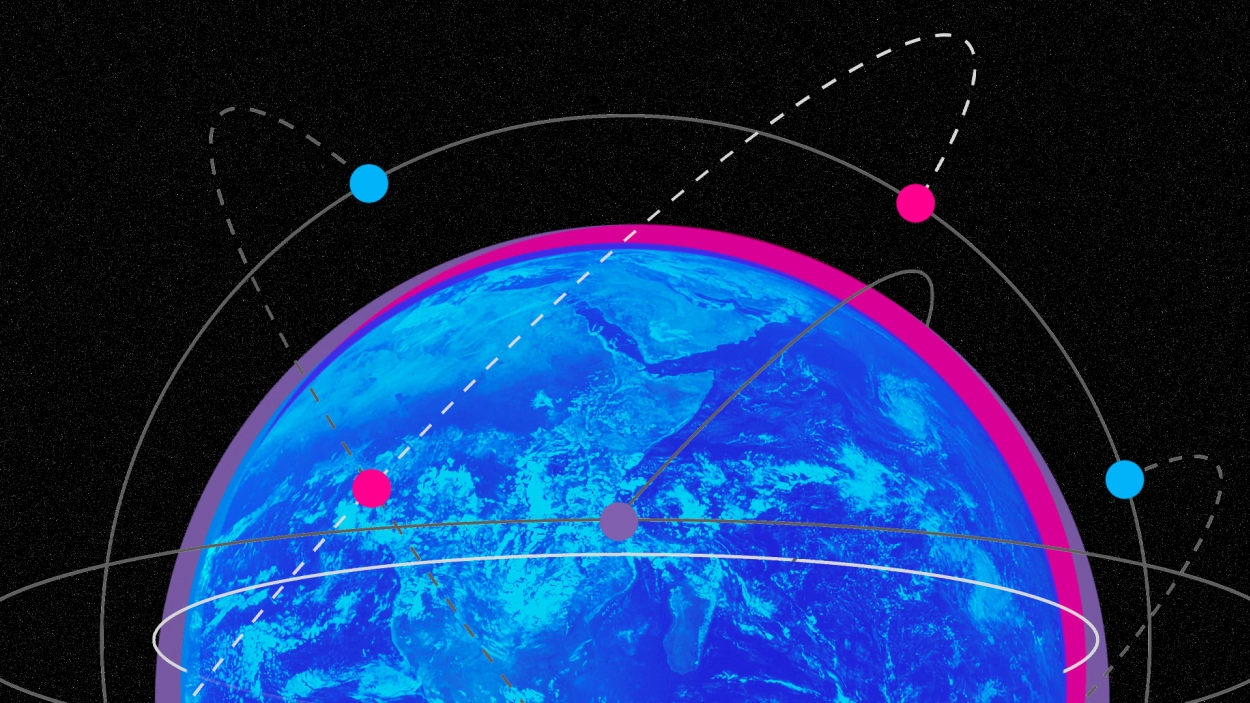

Where other satellite-broadband startups go low, Astranis is going high. This San Francisco-based firm aims to provide cheaper connectivity from space—not with a constellation of compact satellites in low Earth orbit, like the Starlink satellites from Elon Musk’s SpaceX, but with far fewer compact satellites in geostationary orbit.

That 22,236-mile altitude has been the traditional home of communications satellites because placing one over the Equator there will keep it over the same spot on Earth.

“Geostationary orbit is historically one of the most valuable pieces of real estate in the entire solar system,” says Astranis CEO John Gedmark.

But it’s also traditionally been populated by some of the largest commercial satellites sent into space. That’s where Astranis aims to flip the script.

“Can we do something much faster, much lower cost, with small satellites?” Gedmark asks. “The answer was unquestionably yes.”

High hopes for small sats

Astranis’s MicroGEO satellites weigh about 800 pounds, about one-fifteenth of the 13,000-lb. mass of Carlsbad, Calif., space-communications firm Viasat’s upcoming ViaSat-3 broadband satellite.

The tiny nature of a MicroGEO satellite also allows for a rewriting of the geostationary-broadband model. One satellite doesn’t have to cover an entire continent to cover its costs and can instead provide better service to a single region.

“If satellite capacity is very expensive, which it historically has been, then the only way for the economics to work out is that you have to split that capacity across many many users,” says Gedmark.

As a result, what Astranis sees as the next frontier of satellite broadband will start at America’s last frontier. Its debut satellite will provide service to Alaska as resold to local providers by Pacific Dataport, a local telecom provider leasing the Astranis spacecraft christened Aurora 4A.

“The Aurora 4A will enable all Alaska providers to offer broadband at substantially lower prices and much faster speeds, with and without data caps,” says Shawn Williams, vice president of government affairs and strategy for that Anchorage firm, in an email. “Pacific Dataport customers include telecoms, ISPs, tribes, governments, schools, and health clinics.”

Williams did not specify how fast this broadband would be or how much it would cost, but suggested Pacific Dataport could go much better than the status quo in the areas it will serve—which does leaves room for improvement compared to good broadband in the lower 48: With Alaska’s major cable provider GCI, residential service starts with a $80 plan that offers 200 Megabits per second downloads, up to 10 Mbps uploads, and a data cap of just 250 GB.

Satellites for rent

Astranis is also charting a different course from established satellite providers by not selling the satellites it builds.

“This is a bulk-lease model,” Gedmark says. It’s a bit like the mobile virtual network operator model of wireless service, in which a company that sells wireless services to consumers pays a big carrier to provide the underlying infrastructure. Except here the equivalent of the cell tower that’s being wholesaled is more than 22,000 miles taller.

Astranis sets itself apart from other satellite operators in one other way: Its spacecraft feature software-defined radios that can be reprogrammed to use different frequencies as needed instead of having their spectrum soldered in place before launch. Gedmark pitches that as a key to flexibility and also essential for its leasing model, in which one satellite may see multiple customers over an expected eight-year lifespan.

“We can build these satellites as a standard design and then crank them out on an assembly line,” he says. “You can actually dial it in once they’re up in space to use the frequencies you need for that area.”

Adaptability is a good thing, one satellite-industry analyst concurs.

”If Astranis wants to keep possession of that satellite and lease it out, then they want to have more customers and be flexible,” says Tim Farrar, satellite industry consultant and founder of Telecom, Media and Finance Associates.

He adds that Astranis is surrendering a little efficiency: “There is some tradeoff between flexibility and the amount of capacity.”

A long road to a launch pad

All of this is taking longer than Astranis originally expected. At the company’s public introduction in March of 2018, when it announced an $18 million investment from Andreesen Horowitz that represented that Silicon Valley venture-capital firm’s first space funding, it said it aimed to launch in 2019.

In a January 2019 blog post, Gedmark predicted a launch in the second half of 2020. Today, he attributes the delay to pandemic-induced lockdowns and supply-chain issues. “It’s really hard stuff,” he says of the latter. “The whole country could learn a lot from that.”

Then again, Viasat announced its ViaSat-3 project in February of 2016. And yet both that giant satellite—a blog post describes the 144-foot span of its solar panels as “approximately the same as a Boeing 767”—and Astranis’s Aurora 4A are now due to launch early next year.

On the same rocket: The tiny Astranis spacecraft will be a rideshare payload with the large Viasat bird atop a SpaceX Falcon Heavy.

That launch date has slipped as Viasat has dealt with its own supply-chain issues. “You finish your satellite and then you’re waiting on the rocket,” Gedmark says of the schedule snags possible when a satellite takes a metaphorical back seat. “It’s so much better to have your own dedicated rocket–you have that schedule control.”

Astranis has booked a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket to launch its next four satellites—one to be rented by Peru’s Grupo Andesat, two to be leased by the airline and cruise-ship Wi-Fi provider Anuvu, and the fourth to a customer not announced yet.

The Andesat deal provided the only hint of the cost of a MicroGEO satellite, with the announcement citing a $90-plus million value. Farrar says $200 million has been closer to the usual cost for a new communications satellite.

All four satellites add up to far less weight than the Falcon 9 partly-reusable rocket’s 18,300-lb. capacity to geostationary orbit. Gedmark says Astranis won’t sublet the remaining capacity and instead will use the surplus velocity to get those birds to orbit faster.

Smaller rockets right-sized for more compact satellites would be a better fit. “We are very excited about some of these small launchers coming online,” he says of such upcoming launch vehicles as Rocket Lab’s Neutron.

Competing with Starlink

Meanwhile, SpaceX continues to launch its low-Earth-orbit Starlink broadband satellites multiple time a month. Farrar points to that growing constellation and its low-latency service as the single biggest obstacle to any other space-based broadband provider, be it Amazon’s low-Earth-orbit Project Kuiper or Astranis.

“It’s difficult for anyone, whatever orbit they’re in, to compete with Starlink,” he says.

Starlink itself has struggled to keep up with demand, having announced a somewhat soft 1 TB data cap in early November.

Gedmark, however, says there are more than enough unconnected customers to go around. “The market is so massive that we all have our work cut out for us to solve this problem,” he says. “And I think we’re focused on very different things.”

Both Starlink and Astranis aspire to connect the unconnected, but where Starlink’s $110/month service assumes a certain income level, Gedmark says he assumes next to none among the users of the telecom companies he aims to sign up.

“We’re talking about people who might only spend $4 or $5 a month on their cell plan,” he says. Once Astranis can get a satellite in orbit and a wireless carrier can upgrade its cell sites to use its bandwidth for backhaul, all of those users should see a speed upgrade that doesn’t require replacing their phones.

“I see it as the largest market opportunity, and it’s the one that’s the most exciting to us,” Gedmark says. “That’s how you get the largest number of people online.”

(17)