Blocked Shots: How Sportswriter Tim Kawakami Dominates Twitter

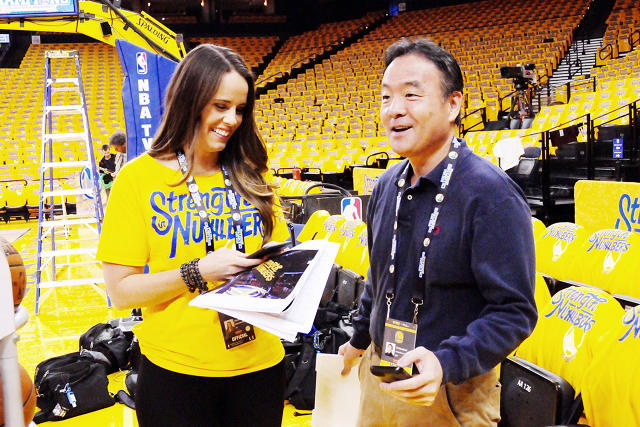

Last year, during the 2015 NBA Finals between the Golden State Warriors and the Cleveland Cavaliers, Tim Kawakami and Marcus Thompson, both sportswriters with the San Jose Mercury News, went out to dinner at a restaurant in Cleveland.

At some point in the evening, two men came up to talk to the writers. It turned out that Kawakami had blocked one of them on Twitter.

Kawakami “came over, and he was like, ‘That guy was blocked by me,’” Thompson says. “They ended up talking for awhile, but it was just funny. [Tim] was a little embarrassed, like, ‘Oh, my bad.’”

Twitter’s block feature allows any user to keep anyone they want from seeing what they post. The tool is often talked about as a way to keep, say, aggressive exes from cyberstalking. For Kawakami, though, he wields the block as a shield against people who tell him what to do, toss racism his way, laugh at him (“LOL”), and any number of other, harder-to-define offenses.

“That’s a big, big, big theme,” Kawakami said last winter during an episode of Warriors Plus/Minus, a podcast he does with Thompson. “You can argue with me. I don’t have a problem with that. It’s when you start saying, ‘You better stop doing this.’ Okay, now, I do whatever I want. I write whatever I want to.”

It’s clearly a frequent problem. If you read his Twitter feed, the phrase “See ya” makes a regular appearance—an indication that someone, somewhere said the wrong thing. As of this writing, Kawakami had blocked 6,483 people on Twitter, up from 6,093 on May 3.

At 50, Kawakami’s been around, starting at the Philadelphia Daily News as an intern, and then covering the Eagles from 1988 to 1990. Later, he went to the Los Angeles Times, where he wrote about the Rams, boxing (see his story about riding in a limo with Muhammad Ali), UCLA basketball, and the Lakers—at their Shaq and Kobe championship peak. Then in 2000, it was on to the Mercury News, where, since 2002, he’s been a general sports columnist covering the San Francisco 49ers and Giants, the Warriors, Oakland A’s and Raiders, and others.

To hear his peers talk about it, he’s one of the most respected scribes in sports.

“I honestly believe that Tim is the best at what he does,” Ethan Sherwood Strauss, ESPN’s Warriors beat writer, says.

If you read any of Kawakami’s prodigious body of work, a few themes come across quickly: One is that he’s got fantastic sources, and reports things—like the inner machinations that led to the end of 49ers head coach Jim Harbaugh’s tenure in San Francisco—well before anyone else.

Another is that he don’t brook no nonsense.

He has no problem speaking truth to power, calling out players and executives when they do dumb things or play poorly. Yet he’s also quick with praise when things are good.

All you have to do to see these dynamics in action is read his coverage of the 49ers—a once proud franchise that has recently fallen from grace—or the Warriors, for decades the NBA’s laughingstock, but now without question one of the league’s best-ever teams.

“He’s one of the hardest-working and most visible columnists that I’ve ever been around,” Warriors general manager Bob Myers says. “He’s certainly not afraid to write something critical because it could have an impact on a relationship. He knows that if someone deserves to be criticized, it’s his job to point that out to his readers in a fair and professional manner. And . . . he will praise a team, player, or organization for a job well done.”

Adds Myers, “That balance is the basis for his credibility. He has a job to do, and that is to provide his opinions to his readers, pro and con.”

Larry Baer, the president and CEO of Major League Baseball’s San Francisco Giants, concurred.

“He’s got great analysis [and] he has great relationships with all the teams,” Baer says. “But the thing about Tim is that he’s not afraid to share his perspective, and I think that makes it a richer content than if you’re just out there reporting it in a straight-line way. It can be risky, and you can alienate, but i think the important thing is he gets it right.”

All of that is noteworthy in today’s sports environment, given how essential access is to writers competing with countless others to constantly bring meaningful news and analysis to audiences hungry for the latest.

“I think a lot of sportswriters don’t want to take risks,” Baer says, “because they don’t want to alienate the people they cover, and I get that, whether it’s the players or the management. But on the other hand, if you don’t take some risks, then it’s pretty dull, there’s no bounce to the stories, and it becomes pretty vanilla. And Tim’s not vanilla.”

Stephen Curry

As this year’s NBA playoffs have progressed, one of the biggest storylines was the health of Warriors superstar and two-time league MVP Stephen Curry. The Baby-Faced Assassin, as he’s known, had suffered through horrible ankle problems earlier in his career, but in recent years had been largely injury-free. That was particularly true this season as the Warriors compiled the league’s all-time best regular season record of 73-9, surpassing Michael Jordan’s legendary 72-10 Chicago Bulls team in 1995-1996.

In the first game of this year’s playoffs, Curry sprained his ankle, and after being out for a few days, suffered a far worse injury, a knee sprain that threatened to derail the Warriors’ goal of repeating as champions.

Back in Oracle Arena, the Warriors’ Oakland, California, home, during that first playoff game, no one knew how severe Curry’s ankle injury was, and desperate fans were begging reporters for answers.

Before and after every game, players take questions from the press corps in an interview room. The word was out that Curry would appear at the podium after the game—won by the Warriors, 104-78.

While most of the sportswriters gathered in the interview room, Kawakami wanted to wait in the hallway to see Curry approaching. Even if he couldn’t ask the MVP questions, he could see whether the 28-year-old star was limping. No one else thought of that.

That ingenuity goes hand-in-hand with his dogged approach to reporting on the many teams he covers, as well as his tireless work ethic.

He posts stories at all hours, tweets relentlessly, and during games, he uses his Twitter account as a kind of play-by-play platform, as well as a place to keep up a running dialogue with readers.

“There are really smart fans out there [on Twitter],” Kawakami says, “and they get me thinking. And you’ll see that lead to something else, or a question I’ll ask an executive or player.”

Over the years, Twitter has become a place that he tests ideas, shares initial thoughts, and, of course, reads what his many peers are writing.

“What I liked about [Twitter] in the beginning,” says Kawakami, who has nearly 72,000 followers, “is that it was a funnel for me to [read] other writers I didn’t know. And those writers led me to other writers who led me to other writers. I picked my own stream of information, and it brought me a lot more diversity than any other way, and outside thinking . . . Who do I want to hear from? Basically, talking to me five times a minute.”

Watching how others did it, he had a pretty good idea he could play the Twitter game, and do it in all the ways that others were doing, as well as interact with fans and kickstart his own stories.

It’s easy to see. Scroll through Kawakami’s Twitter feed on any given day, and you’ll see a mix of tweets. Many will be musings on game action or a player trade, or someone else’s story. Quite a few will be him answering readers’ questions.

The trouble begins when fans fight back against any number of those musings. There’s a lot of people on Twitter looking for fights, challenging his interpretations or facts, and Kawakami is the last one to shy away.

“I just don’t like stupidity,” he says, “and I will respond to stupidity if I feel it’s representing the larger stupidity.”

He says anyone can disagree with him, respectfully, but when it comes to telling him what to do, he simply ain’t having it.

“It’s fascinating to me, but it also becomes almost a challenge to me,” he says. “Am I going to not respond to idiocy? And I almost always do . . . I tell myself it’s to expose idiocy, to say, ‘Hey, it’s an open conversation. I could be wrong.'”

In many cases, he does his blocking silently. But it seems like almost every day, he pulls out his “See ya” and blocks someone in front of the whole world. It’s almost like he relishes the opportunity.

“No question” that’s true, Thompson says. “He could block and just not say anything. Tim, he wants you to know that he’s out here slapping people on Twitter, and it’s his reputation. He has to make an example out of you. He’s got about 15,000 examples.”

That reputation is interesting. I mentioned that I was working on a story about Kawakami to a professional acquaintance who’s a very big Warriors fan—saying nothing else about the story—and this is what I got back: “He blocked me on Twitter a few years ago for questioning some opinion of his. I think he gets off on doing that; seems he blocks followers for the most innocuous of comments.”

Erik Stern, a 36-year-old San Francisco Twitter user, recently got into a brief back and forth with Kawakami over a column he’d written about Curry’s defense, which had been famously mocked by Oklahoma City Thunder star Russell Westbrook during this year’s playoffs. Kawakami’s column argued that Curry’s D can be both good and bad, as it had been during two losses to the Thunder.

Stern objected to the bit about bad defense, tweeting, “What’s your evidence?” along with stats demonstrating that Curry had locked Westbrook down. When Kawakami reacted in a sarcastic style familiar to his readers, Stern tried again, replying with a challenge and implying that Kawakami was slagging off Curry’s defense. He also added this: “Please don’t block.”

Too late. Kawakami fired back: “Good lord. 1—Where did I say he was bad? In fact I stressed he is pretty good. 2—You’re blocked anyway.”

Having witnessed a lot of Kawakami’s Twitter battles in the previous months, I was a bit taken aback. Stern hadn’t told him what to do, and hadn’t laughed at him.

I asked, “Why Stern?”

“One of the beautiful things (for me) and random things (for others, probably) is that I don’t have a policy for this,” Kawakami wrote me at 11:30 on a work night during the NBA Finals, “and I don’t go back and look at how or why I did what I did. With the exception of when Marcus Thompson brings them up to me on the podcast. If it was a quick trigger, so be it. If it wasn’t, so be it. I don’t look back.”

Block Amnesty

Kawakami’s penchant for blocking people on Twitter is actually something of a joke between him and Thompson. Together, they’ve covered the Warriors for years, and last fall they launched a podcast about the defending NBA champions, knowing their conversations about the team would be popular.

Anyone who’s tuned into Warriors Plus/Minus, with guests like Curry and fellow All-Stars Klay Thompson and Draymond Green, and head coach Steve Kerr, knows the show is a can’t-miss source of colorful inside information about one of the hottest teams in sports.

Early in the show’s run, though, Thompson announced a Tim Kawakami Twitter block pardon program.

Right away he was flooded with clemency pleas. Culling the submissions for a case he could win, he settled on a 15-year-old journalism student who’d been blocked for telling Kawakami to take something back about a favored ex-Warrior.

Kawakami relented, saying during the show’s second episode, “I can’t believe I’m this easy on the first one . . . but the 15-year-old part of it is what gets me.”

The next episode went the same way, with Thompson successfully defending a Kawakami blockee. But after that, Thompson says, there were simply too many requests.

Truth To Power

Even as he calls Twitter users on their “idiocy,” one of the things that’s earned Kawakami substantial respect is that he does the same to players or team executives. In years past, a prime target was the Warriors, before they became world beaters. More recently, the 49ers have often been in his crosshairs.

On Twitter, people complain that all he ever does is slam the Niners, to which his common refrain—accompanied, perhaps, by a block—is to demand readers come up with something good the NFL team has done that he hasn’t praised. They never can.

As for the Warriors, he’s regularly accused of being a “homer” who endlessly praises the team to curry favor. His response is to remind people how often he’d slammed the Warriors when they were terrible. Even as recently as last month, as the defending champions looked like they were about to be eliminated by Oklahoma City, Kawakami wrote that the team was looking feeble against the underdogs.

“With long arms and great agility,” he wrote, “the Thunder has made Curry and Green look slow and tired, a bit frustrated and more than a little shell-shocked.

“Nobody else in the league has done this for two seasons, and right now it looks like the Warriors can’t stop Oklahoma City from doing it.”

Kawakami says that his penchant for being tough on teams began early in his career, when he was in Philly covering the Eagles.

“I was just curious,” he recalls. “I wanted to ask questions, and when I ran into people who couldn’t answer them, my frustration was everyone’s frustration. ‘Why aren’t you answering this question?’. . . If you can’t answer the question, what does that tell me about you?”

The problem many sportswriters face in trying to take in the flood of information from teams is interpreting it, understanding what’s real and what’s spin—which is Kawakami’s enemy.

“He doesn’t fall for the banana in the tailpipe, so to speak,” says Thompson. “If you throw BS his way, he’s going to call it, and he’s gonna stand up for himself.”

That approach has earned Kawakami an invaluable set of sources, even among people who may not like it when he turns his gaze on them.

“He gets as many scoops as anybody out here,” Thompson says. “People talk to him, so you know if you suck at your job, Tim is going to call you on it . . . The problem ain’t with Tim. The problem’s with you. If you can’t look at facts and analyze them properly, that’s not Tim’s fault.”

Both Thompson and ESPN’s Sherwood Strauss say they learn a lot watching Kawakami write honestly, good or bad.

“That’s probably the one thing I’ve always taken from Tim, that in the long run, do what you know is right, because not doing it, there’s no benefit,” Thompson says. There are “people who defend owners, who go the extra mile, and in the end, it’s still Tim getting the scoop.”

Sherwood Strauss agrees.

“It was a big deal when I was just starting out,” he says, “just to see [Kawakami] work . . . Just seeing Tim ask adversarial questions, asking the questions that were on people’s minds [when the Warriors were awful]. That informed my sense of how to do the job.

An Expensive Tweet

What’s the most a tweet has ever cost you? For Kawakami, it was $2,100.

In 2014, as the San Francisco 49ers were in the process of building a new stadium in Santa Clara, California, he bet team owner Jed York on Twitter that the facility wouldn’t be done by the end of the year.

As he related the story in a podcast in late April, the bet was for lunch in Napa, California’s famous wine capital. Over time, it evolved, eventually becoming dinner at the French Laundry, the Michelin three-star culinary shrine. When the stadium was finished on time, Kawakami had to make good.

York had apparently asked if he could bring along—and pay for—his wife, but when the bill came, the billionaire made no move to fork over for her.

It cost Kawakami $2,100 to settle up, and on the podcast, he explained he’d never said anything about the incident because he didn’t want people thinking his frequent negative articles, tweets, and on-air comments about the 49ers were about anything but the team’s disastrous play and tragic management decisions. Nevertheless, he explained, the team had concluded that he had an axe to grind over the dinner tab.

The podcast had been live for several weeks when Deadspin discovered it, and the story became national news. For a day or two, Kawakami’s Twitter feed was flooded with people accusing him of being a sore loser.

“The bet took place two years ago, and Tim has never shared his concerns about the dinner with me,” York eventually told ProFootBallTalk. “I am happy to speak with Tim one-on-one so we can all move forward.”

Two weeks earlier, the 49ers had told me in response to questions about the incident, “We certainly understand and respect the role the media plays in our business—helping to keep our fans informed about our team. Unfortunately, we do not make a practice of commenting on members of the media, their speculation, or the reasoning behind what they write.”

‘I’m The Worst’

As Kawakami fended off angry 49ers fans, he trotted out one of his favorite lines: “I’m the worst.”

The way he uses the phrase varies, but invariably, it’s his way of sarcastically replying to an angry Twitter user.

When setting out to write this story, I had started to keep track of Kawkami’s combative tweets so that I could return to them to use in this story. The reality? It would be impossible, given how often he gets into it with readers.

That he would block more than 6,400 people is notable. In the parlance of big-time rim defenders in basketball, Kawakami’s quick trigger finger is his version of, “Get that shit out of here.”

What’s equally notable is what his penchant for blocking people means for his readership.

Twitter’s “an interesting [thing],” Kawakami said over breakfast at a packed, loud pancake house in Redwood City, California, earlier this spring. “It’s the first time journalists have had the chance to deny someone something of what I do. Not my stories, but I don’t want to hear from you. I don’t. So don’t read me. Don’t read me. I’m okay with that.”

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(38)