Could Biofortified Crops Be The Key To Solving Global Hunger?

For around 2 billion people in the world, a meal is not necessarily a source of nutrition. Among the poorest populations, starchy staple crops like potatoes and cassava make up the bulk of people’s diets. The people surviving off these crops “may not feel hungry,” says Bev Postma, CEO of HarvestPlus, “but they’re not getting a diverse, nutritious meal, and this ‘hidden hunger’ can lead to blindness, disease, and stunting.” For children under the age of 11, who grow up without consistent access to adequate nutrition, the developmental effects are irreversible; mothers who lack essential vitamins and minerals are unable to pass them onto their children.

HarvestPlus is working to eradicate the hidden hunger epidemic—not by diversifying the crops that people rely on most, but by ensuring that those starchy staple crops also deliver essential nutrients like zinc, vitamin A, and iron, which are too often missing from people’s diets.

HarvestPlus uses a process of biofortification. In the early 1990s, the company’s founder Howarth Bouis, who at the time was working as an economist at the International Food Policy Research Institute, got interested in the idea that crops themselves could provide some of the crucial micronutrients that were reaching developed countries in the form of supplements, through a delivery and development system that required billions of dollars to sustain. “His idea was: ‘Why can’t we solve nutrition with the very foods people are already eating?’” Postma tells Fast Company.

That line of inquiry led Bouis to the Plant, Soil, and Nutrition Laboratory at Cornell University, where he encountered several researchers looking into the potential of cross-breeding plants to result in higher nutrient levels, without compromising yield. He teamed up with scientists who were piloting an orange-tinted sweet potato high in vitamin A in Mozambique, and others breeding cassava and maize tinged with extra vitamin A. However, the concept was still relatively new–the term “biofortification” wasn’t coined until 2001–and Bouis struggled to find funders to support the research and pilot programs that would prove his concept. “He basically went around with a tin cup for 10 years, looking for funds,” Postma says. That is, until he met Bill Gates.

“Bill Gates is a huge fan of cassava–he thinks it’s an amazing crop that has the potential to transform Africa’s future,” Postma says. In 2003, The Gates Foundation gave Bouis a $25 million grant to prove that high-nutrient crops could be produced using basic plant breeding, without leaning on genetic modification. To do so, he visited seed banks around the world, consulting with breeders to determine that crossing higher-nutrient strains of crops could eventually result in those that contained adequate nutritional levels. Bouis was aiming for a single cassava, for instance, that could contain 100% of a child’s daily dose of vitamin A.

He published several papers on his research, proving the concept, and then, working with the Consultative Group on International Agriculture (CGIAR), a coalition of 16 organizations specializing in global crop development, Bouis launched HarvestPlus in 2003. For the first five years, the organization identified target populations–sub-Saharan Africa, rural India–where hidden hunger was most prevalent, and solidified research to prove that biofortification could scale.

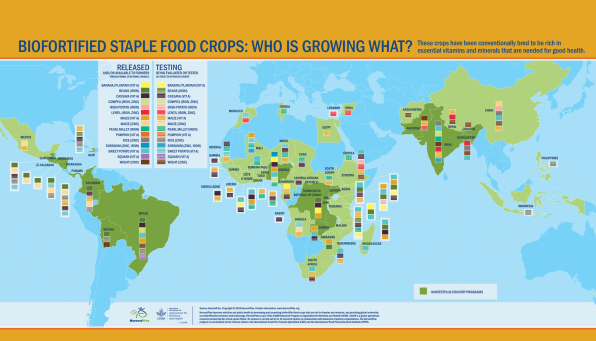

In 2009, HarvestPlus began rolling out the first wave of biofortified crops. The organization focused on 12 staple crops–wheat, maize, sorghum, cassava, beans, and millet, to name a few–and three micronutrients: vitamin A, zinc, and iron. “In the world generally, deficiencies in these three nutrients track poverty,” Postma says. “What we’re finding is we have to tackle all three at the same time.” The organization’s biofortified crops, she adds, can supply children and mothers with up to 100% of their daily nutritional requirements.

The key to HarvestPlus’ success–why it’s already reached 20 million people across Asia, Africa, and Latin America–is that it does not require a behavior change on the part of the people it’s working with. “It’s very hard to get people to change their eating habits,” Postma says. “We’re instead seeing what’s already on their plates, and doing a like-for-like swap for an ingredient with more nutrients.” If people are already eating beans, HarvestPlus will swap in beans supplemented with iron; if people are baking bread or chapatti, HarvestPlus will get them wheat fortified with zinc; if people cook cassava or maize, they can do the same with vitamin A-tinged vegetables.

Rolling out the fortified seeds into communities, Postma says, is a multi-stage process. The “introduction” stage is heavily driven by donors. The Gates Foundation, as well as USAID and the U.K. government, equip HarvestPlus with the funding to develop the seeds and distribute them to the agricultural research centers in each country. Those agencies commercialize the seeds and sell them to farmers, and HarvestPlus does on-the-ground community outreach to educate the farmers about the benefits of the seeds. That could look like anything from working with the lead farmer in the community to pilot the seeds and inviting other farmers to sample the crops, to working with doctors in some of the more developed markets in Asia to prescribe zinc rice to children to support development. In the “scale” phase, HarvestPlus works to get the seeds into the hands of more farmers, and in the “anchor” phase, they look to create a market presence for the crops, so they become independently economically self-sustaining.

While the deployment strategies differ widely by country, the transition, once HarvestPlus is established, is generally smooth: Once the farmers are convinced that the new crops are climate and pest resistant, and won’t lower their yield, they can switch seamlessly to the new seeds after a harvest. Once farmers grow the seed, the nutrients remain in the crops for future harvests. And while HarvestPlus has yet to publish their findings on taste, as they’re only just beginning to research them, a blind taste-test in Zambia found that children actually prefer the orange, vitamin-A tinged corn to white corn. It tastes sweeter to them, Postma says, though their scientists are not yet sure why.

HarvestPlus has been selected as one of the eight semi-finalists in the MacArthur Foundation’s 100&Change competition, which will give a $100 million grant to a single proposal that promises a real and measurable solution to a pressing problem of our time; winners will be chosen later in the summer. Whether or not HarvestPlus is awarded the grant, Postma says the organization is committed to reaching 1 billion people by 2030.

While HarvestPlus’ work is among the most straightforward and scalable approaches to solving hunger out there, Postma is clear-eyed about the situation they’re tackling. “This problem long term can only be resolved by lifting these people out of poverty,” she says. “Let’s be very clear here: Whatever HarvestPlus is doing is just bridging that gap that shouldn’t be there in the first place.”

HarvestPlus is growing staple crops saturated with essential nutrients–vitamin A, zinc, and iron–to drive down rates of “hidden hunger” and developmental deficiencies.

For around 2 billion people in the world, a meal is not necessarily a source of nutrition. Among the poorest populations, starchy staple crops like potatoes and cassava make up the bulk of people’s diets. The people surviving off these crops “may not feel hungry,” says Bev Postma, CEO of HarvestPlus, “but they’re not getting a diverse, nutritious meal, and this ‘hidden hunger’ can lead to blindness, disease, and stunting.” For children under the age of 11, who grow up without consistent access to adequate nutrition, the developmental effects are irreversible; mothers who lack essential vitamins and minerals are unable to pass them onto their children.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(22)