Delivery 2.0: How on-demand meal services will become something far bigger

The U.S. app-based delivery economy took shape in the first half of the 2010s as services such as Instacart, DoorDash, Uber Eats, and Postmates came online and early pioneer Grubhub went public. But it took until this decade for the industry to experience its catalyst event.

Seemingly overnight, these apps expanded beyond convenience portals to essential services. As the CDC urged Americans to go online for groceries and meals, app downloads and orders skyrocketed. The food delivery services more than doubled their revenue while Instacart hit its 2025 projections five years early.

The flurry of activity in 2020 was nonstop: Uber acquired Postmates, Grubhub found a buyer of its own, DoorDash went public, and Instacart doubled its valuation after a fresh funding round. Now, one year into the decade, the robust market opportunities available to delivery platforms are more apparent than ever. But the landscape has also never been more competitive, and today’s platforms are far from optimized for the consumers and merchants they serve.

Let’s break down some key challenges these platforms need to overcome and explore the ways they are likely to adapt in the 2020s.

Solving the profitability problem

First, platforms continue to operate on razor-thin margins, where 1% margin improvements often mean 50% profitability increases. While DoorDash turned a $23 million profit in Q2 2020, spurred by pandemic-driven order growth, it returned to a loss in Q3 and has yet to see meaningful long-term profitability. Entering 2021, Wall Street analysts continue to reduce bullish growth projections, with post-IPO consensus largely mixed and the stock’s future still hazy.

Uber Eats and Grubhub are faring no better. While Grubhub managed to eke out a DoorDash-esque $44 million profit in Q3 2020, Uber’s delivery business posted a staggering $183 million loss (both are adjusted EBITDA). The shaky hold that even established, public companies have over immediate profitability bodes poorly for the industry’s long-term financial prospects.

Lack of loyalty

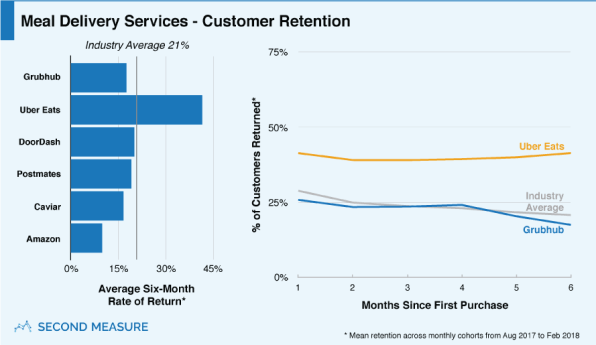

Second, when it comes to delivery platforms, the end consumer has little loyalty, scouring multiple platforms to identify the best deals for their favorite meals. As a result, consumer retention has been poor, with the average 6-month customer return rate for all delivery platforms at a meager 21%. In fact, all major platforms (Postmates, Caviar, DoorDash, Grubhub, Amazon) post return rates below the average, with only Uber Eats’s above-30% return-rate raising the average, driven by cross-selling with its ride-share platform.

Even with the largest customer footprint, Amazon failed to cost-effectively operate last-mile food delivery (Amazon Restaurants) for early customers from its centrally located warehouse network and was forced to shut down the four-year experiment in late 2019.

In a competitive market with thin margins and a clear lack of loyalty, recurring problems continue to plague the end-user consumers and merchants. It is no secret that all delivery platforms tack on 20%+ commissions to merchants, grinding already thin restaurant margins into oblivion. While national quick-serve chains can still see profitability from low-margin orders at scale, the mom-and-pop restaurants that are the bread and butter of delivery platforms will inevitably struggle to stay afloat paying these commissions.

If the merchants are squeezed for pennies, so are the consumers—as the hefty delivery and marketing costs are borne by both sides of the marketplace. On a standard Subway order, the major delivery apps marked up the final consumer price a minimum of 25% (Grubhub) and a maximum of 91% (Uber Eats). Consumer frustration with price markups drives significant dollars away from platforms’ bottom lines—reflected in the fact that the pre-pandemic market for pickup and drive-through ordering was 10 times the market for deliveries, as ultimately, ordering ahead and picking up just hurts consumer wallets far less than exorbitant delivery fees.

If platforms do not evolve their cost structure while continuing to improve speed and quality, they risk competing in a race to the bottom that continues to alienate merchants and consumers.

The next decade of delivery

The optimal method to retain and engage customers in the next decade of delivery will be to disaggregate the consumer-facing brands from the delivery infrastructure—enabling a capital-efficient “front end” that drives up merchant profitability and decreases the burdensome cost passed along to consumers.

Eventually, our belief is that last-mile delivery will follow an Amazon-esque growth trajectory to transform from a logistics provider into a sticky consumer platform. Last-mile platforms will become the aggregators of hip and trendy restaurant brands and will own the ensuing customer relationships and loyalty through cross-promoted services such as Dash Pass or Postmates Unlimited. And with a critical mass of brands, each platform can unlock new revenue streams through in-house advertising networks, where small mom and pop restaurants and large chains like Applebee’s alike will pay for sponsored search results, promotions, and more.

We need only to look to China for a strong case study—incumbent delivery platform Meituan has been operating this advertising model successfully for years, using it to drive the core enterprise value as reflected in its May 2020 valuation of $100B.

Invisible kitchens

Burritos Locos? Impasta? SushiBi? A late-night browse of food delivery apps will surely reveal a host of new restaurant names that may pique your taste buds, but you have no recollection of. To sift through, you’ll swipe through carefully curated photos and most importantly—user reviews.

So, what is a restaurant brand today? It’s a well-advertised digital storefront, ideally with more than a hundred well-written, 4+ star user reviews, that can place food at your doorstep within 45 minutes. While the post-2010 “delivery 1.0” phase saw the rise of major delivery platforms that brought offline restaurants online, the post-2020 “delivery 2.0” phase will see the rise of delivery-only brands that never physically existed at all.

The proliferation of ghost kitchens will democratize access to food entrepreneurship.

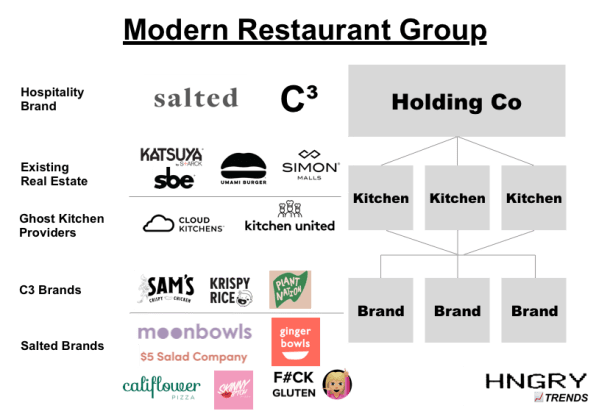

Delivery-only brands are made possible through the rise of ghost kitchens—third-party fulfillment centers that cook and batch for a variety of brands. Travis Kalanick’s CloudKitchens enables independent restaurateurs to lease kitchen space and quickly spin-up food brands for delivery. Delivery-only restaurant groups such as C3 and Salted have acquired their own ghost kitchens from which to drive multibrand fulfillment for L.A. favorites such as Skinny B*tch Pizza and Sam’s Crispy Chicken. Companies such as Zuul are providing software-as-a-service licenses to restaurant owners that can effortlessly convert any kitchen into a ghost kitchen.

The proliferation of ghost kitchens has created a “restaurant in a box” technology stack that will democratize access to food entrepreneurship. While opening a restaurant or convenience store has always been seen as a capital-intensive operation, requiring significant real estate and inventory investment, anyone with a menu and branding expertise can now leverage third-party fulfillment to spin up a new delivery concept.

Even for chains or restaurants with an existing brick-and-mortar presence, a suite of delivery-only brands can enable hyperlocal targeting of customers, where menu items are broken down into separate brands to drive visibility and quick experimentation. And each kitchen itself can be used by a multitude of chefs and brands, ensuring that otherwise idle capital-intensive kitchen real estate is being used at its full capacity.

Future-proof branding

Restaurants need not rely on conventional branding techniques to build new delivery concepts. The most promising concepts of the future will rely on existing media, entertainment, and sports intellectual property that can drive home customer engagement for food brands and IP owners alike. L.A.-based Team Kitchens has partnered with the Dodgers to deliver the fan-favorite Dodger dog and other team-branded fast food items through Postmates. As the model continues to be replicated by teams nationwide, fans will be empowered to recreate a part of the game experience in the comfort of their home.

Similarly, offline recreations of fictional food items, whether Harry Potter’s butterbeer in Universal Studios Hollywood or burgers sold out of a Krusty Krab replica in Palestine, no longer have to be limited to theme parks or even physical locations. In partnership with movie and television studios, superfans with a knack for menu creation can collaborate with ghost kitchens to spin up delivery concepts that cater to a wide range of entertainment niches. Such concepts are already popping up. The famous fried chicken restaurant of Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul, Los Pollos Hermanos, is a ghost kitchen-fulfilled brand delivered on Postmates.

Perhaps even YouTube cooking channels such as Strictly Dumpling, with existing recipe how-tos and brand assets, can create ghost kitchen-fulfilled offerings of their favorite dishes, delivered through DoorDash or Postmates. In partnership with platforms such as Cameo, these dishes can be delivered “by the celebrity” with personalized shoutout videos attached alongside delivery confirmations. For rising YouTube stars and popular TV series alike, branded merchandise and social media interaction are table stakes in today’s digital world—food delivery could be the necessary next step in building true offline presence and engagement with fans beyond traditional merchandise sales.

More than just a meal

Just as DoorDash, Uber Eats, and their peers will be the one-stop shop for food, there is immense potential for other last-mile platforms to fill a similar gap in grocery and consumer packaged goods.

When consumers visit a grocery store today, they are placing trust in the store and its brand. You trust Whole Foods to provide you with high-quality, organic products. You trust your local butcher to sell you high-quality, clean cuts of meat that have been kept at the right temperature and for the right duration.

A new swath of delivery platforms will each replace different consumer behaviors.

But when consumers order delivery, they introduce an intermediary—the last-mile platform—that they are placing their trust in as well. And soon, this will be the status quo for everyday shopping; no more daily trips, long lines, and pockets full of mile-long CVS receipts. With almost 70% of Americans intending to use grocery delivery post-pandemic, platforms such as Instacart, much like their meal delivery counterparts, will soon be the primary owners of customer relationships.

A new swath of delivery platforms will each replace different consumer behaviors. GoPuff in the U.S. and Fancy in the U.K. will deliver convenience items and alcohol to urbanites in under 30 minutes. Whether you need a savory snack to get you through a long workday or a couple of extra drinks for your evening guests, these platforms will save customers the dreaded last-minute treks to convenience stores and provide near-instantaneous gratification.

Similarly, Instacart and traditionally grocery-only platforms will slowly become the universal storefront for all consumer goods. These platforms will aggregate and save consumers hundreds of annual trips, from the daily visit to the baker to the weekly trip to the grocery store or even monthly sprees at favorite mall retailers. And as with meal delivery platforms and China’s Meituan, Instacart and others will operate advertising networks that will be the new default by which consumers discover and engage with brands. Even today, Instacart already has over 1,000 brands, including all top 25 CPG brands (from Procter & Gamble, Pepsico, and the like) signed on as platform offerings and advertising partners. With time, we believe that even niche, ethnic delivery platforms such as Weee! (Asian) or Subziwalla (Indian) will expand beyond groceries and help introduce well-loved international CPG brands to U.S. consumers.

A decade of innovation awaits

The pandemic has proven to be a true catalyst event for the adoption of digital delivery services. Even as these platforms have reached meaningful scale, however, it’s become clear the current playbook is not viable in the long term. It’s the orchestration of media brands, supply chain operators, and last-mile platforms themselves that will inevitably usher in the era of “delivery 2.0.” Once this decade comes to a close, we can be certain of one thing: The delivery platforms of the future will be virtually unrecognizable compared to today’s apps, and that transformation will be to the benefit of all parties involved. Founders, consumers, and merchants beware—the future of commerce is here.

Sunny Dhillon is a founder and partner at Signia Venture Partners, an early-stage venture capital fund in Silicon Valley and Los Angeles. Kevin Wu supports the investment team at Signia Venture Partners.

(30)