Google Hopes Taylor Swift Will Finally See Green In YouTube Red

Since the freewheeling, Napster days of digital music, artists and labels have been forced to accept some very hard realities about their industry. From peer-to-peer piracy to the life-preserver Apple tossed out to record companies in the form of iTunes, to the rise and dominance of streaming services, upheaval has been a mainstay of music’s relationship with computers. But the Silicon Valley side of the equation has had to swallow a difficult truth as well, and one that’s inimical to a tech industry built on advertising: In music—as with other kinds of creative and professional pursuits online—paying subscribers are a far more sustainable source of revenue than free users who look at ads (which, in any case, they are increasingly trying to block).

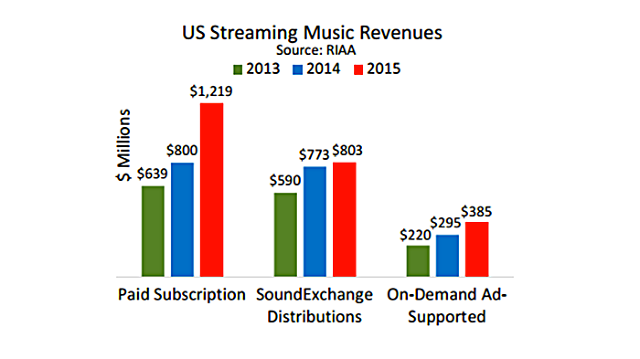

Last year, according to the Recording Industry Association of America, subscription streaming services like Apple Music and Spotify’s paid tier generated $1.2 billion, amounting to about half of the revenue for the entire U.S. streaming industry. Meanwhile, ad-supported streaming—which includes Spotify’s paid tier along with YouTube’s massive video platform—only generated $385 million for the U.S. market in 2015.

That revenue gap becomes even more dramatic when taking into account the RIAA’s estimate that only 10.8 million Americans paid for streaming subscriptions last year on average, while the number of ad-supported streaming customers includes YouTube’s 200 million monthly users in the U.S., plus millions of Americans who listen to Spotify’s free ad-supported option. Put another way, the average listener of an ad-supported streaming service was worth less than $2 to the music industry in 2015, while the average paid subscriber was worth $120. (The remaining $803 million in streaming revenue, labeled under “SoundExchange Distributions,” came from Internet radio services like Pandora.)

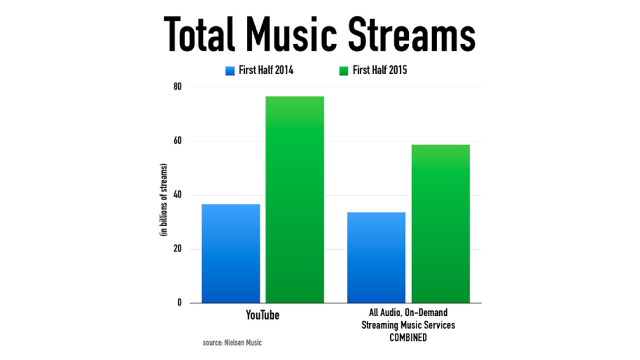

It’s little wonder then that the music industry has soured on ad-supported streaming. And with superstars like Taylor Swift and U2 serving as the industry’s public face, labels and artists have launched a number of campaigns this year that cast YouTube as Public Enemy No. 1. YouTube, the industry has pointed out, is not only the most popular platform for free ad-supported music streaming, but during the first half of 2015 there was more music streamed on YouTube than on all other streaming services combined. Yet Spotify has been paying out more to rights holders than YouTube has been—not just per user, but in total as well.

Granted, the launch of Apple Music along with Spotify’s continued growth have eaten into YouTube’s share of the streaming pie: According to Nielsen, YouTube now only accounts for 45% of streaming music in the U.S. But that’s still a huge market share for a company that, in terms of revenue, isn’t pulling its weight.

And how could it? Without a subscription option for most of its existence, YouTube could only generate dollars through digital advertising—a market that has added less than $100 million in new streaming revenue each year, despite the rapid growth of YouTube as a destination for music fans. YouTube likes to point out that it’s given back $3 billion to the music industry throughout its decade-plus existence. That’s fine, but if the streaming market continues on its current growth arc, it won’t be long before the rest of the industry is giving back $3 billion each year. Meanwhile, YouTube’s advertising revenue—barring either a massive change to the way advertising on YouTube works or a dramatic migration of ad inventory from television and terrestrial radio to digital platforms—will continue to lag behind.

The Promise Of Red

These are all reasons why the industry has long been clamoring for a paid subscription option from its largest streaming partner, YouTube. And in October of last year, labels and artists got their wish with the launch of YouTube Red, a $9.99-per-month subscription service that offers ad-free streaming as well as access to exclusive content.

Now that it has a paid subscription option like Spotify and more recent entrants like Apple Music and TIDAL do, it’s logical to assume YouTube will begin to generate more revenue for the music industry, based on the charts and figures cited above. YouTube’s chief business officer believes so, too; in an interview with the Financial Times, Robert Kyncl mentions YouTube Red as a new source of revenue for disgruntled rights holders who feel like they haven’t received a fair shake.

But in talking to individuals inside the music industry, including those who work on behalf of major labels and independents alike, their outlook for YouTube Red is far less optimistic.

“We don’t disagree with YouTube’s claims that subscription is more meaningful,” said one industry source. “But how many people are they able to convert? Are they really going to convince people to pay? There’s a lot of other content in [YouTube Red]. Does music get diluted?”

A Focus On Videos Over Music?

These comments speak to two of the biggest concerns over YouTube Red: The relative lack of promotion for the service’s music-based features and the concern that Red will be viewed by consumers less as a music platform competing for hardcore music fans against the likes of Spotify and Apple Music, and more as a premium video service like Netflix or Hulu.

Indeed, Red’s most heavily publicized feature—and one that will demand heavy investment from YouTube—is its slate of original video series and films. Some of these, like an episodic adaptation of the Channing Tatum franchise Step Up, are being produced in partnership with major networks, film studios, and directors like Ron Howard and Morgan Spurlock. So far, though, the bulk of the shows on the service are designed around gaming and wildly popular YouTube personalities like PewDiePie.

Though 18-24-year-olds are more likely than any other demographic to pay for music, according to Cowen’s 2016 Consumer Internet Survey, many in the industry are concerned that YouTube’s young target audience won’t be as willing or able to fork up $10 a month. According to discussions with major and independent labels, there’s a worry that the younger target audience for Red is not made up of the kind of music superfans willing to pay just to avoid hearing ads in between their favorite songs. For many in the music industry, “Come for PewDiePie, stay for Taylor Swift” simply isn’t a compelling user acquisition model, especially when services like Spotify and Apple Music already exist to serve a market of devoted music listeners.

Compounding the issue is the fact that the company has shifted its compensation metrics away from rewarding videos with high numbers of “views” toward rewarding videos with longer “watch times” that keep users on the site. Is a 30-minute television program worth 10 times as much as a three-minute song? Or should there be more nuance to the calculations? Regardless of the answer, this change is yet another factor that tempers the industry’s excitement over YouTube Red and its ability to fill the current revenue gap in streaming music.

The company admits there’s a lot of room for the $9.99 a month service to grow. “Though it’s still early days for YouTube Red, we’re pleased with the progress of the service nine months in, and plan to expand its availability overseas in the coming months,” a spokesperson told Fast Company.

Earlier this month, YouTube’s head of global content, Susanne Daniels, said that subscriptions to Red had “far exceeded their expectations” since its debut, and that the company planned to pour more resources into creating more and better content for those subscribers.

The company also pointed to an aggressive new advertising campaign it launched last month to promote the YouTube Music app which, according to Billboard, is aimed at converting YouTube Red subscribers. The free app, which YouTube released in November 2015, allows users to find songs on YouTube using a music-only filter, which creates a full on-demand streaming experience on mobile, not unlike what Spotify and Apple Music offer for $10 a month (Spotify’s free mobile offering is extremely limited by comparison). Moreover, new users receive a two-week free trial of YouTube Red, which includes the added benefit of removing ads from the platform.

YouTube CMO Danielle Tiedt told Billboard that the campaign’s five videos, each starring a different character from a marginalized background using the YouTube Music app, is the “biggest campaign we’ll run this year.” And so far the promotion has been a huge success: Last week, YouTube Music knocked the wildly popular Pokémon GO out of the top spot of iTunes’ free app charts. That should at least partially soothe the frustrations of music industry insiders still left unconvinced of YouTube’s commitment to promoting Red.

But all the commitment and promotion in the world isn’t a guarantee that users will stick with Red after the trial period runs out, and they’re forced to pay $9.99 just to avoid ads. And if the vast majority of users don’t stay with Red after they have to start paying for it, YouTube Music’s popularity boom could actually hurt the industry, giving YouTube’s free ad-supported streaming—and the dismally low payouts to artists and labels that come with it—an even bigger share of the streaming market versus the more lucrative subscription services.

Nevertheless, it’s true that YouTube has met most of the industry’s demands when it comes to building a subscription service and—as of last week, at least—promoting it to some extent. However, there’s one longstanding point of contention surrounding Red that, in the minds of many artists and labels, YouTube hasn’t yet satisfactorily addressed. Last year, questions were raised over YouTube’s demands that whatever music artists make available on YouTube’s free site must also be available on Red.

Artists like cellist Zoe Keating were frustrated with this mandate because it places limits on artist control. If artists were permitted to include one of two songs off an upcoming album for free on YouTube.com, while making their full catalog available only to paying customers, that would serve the dual purpose of granting artists more control over their own promotion while also driving more users—and not just any users but, crucially, music fans—to YouTube’s paid site. YouTube would not comment on artist contracts, but the industry representatives I spoke with say their artists still crave that control.

But there’s a separate point raised here that’s left many skeptical over YouTube Red’s ability to attract music fans as subscribers: If virtually every song on YouTube Red is also on Youtube.com and the YouTube Music app for free, why would anybody—fans of PewDiePie and Step Up notwithstanding—sign up for the service?

“Almost all of [YouTube Red’s] content is available on an ad-supported tier, and they’ve trained their consumers that they get this for free,” said one industry source. “The ad-supported tier has to be changed in a way that doesn’t cannibalize from people who have the willingness to pay and want to have a quality paid experience. I think that’s priority number one. The differences in the service between ad-supported and paid is negligible. It’s just not enough.”

YouTube is the only streaming music service that offers full on-demand streaming on all platforms—mobile and desktop—regardless of whether the user pays. (By “on-demand,” I mean that users can search for a specific song and then hear that song immediately.) Apple Music offers the Beats 1 radio station to free users and nothing else. Aside from a 30-day trial period, TIDAL offers users nothing for free.

Spotify, meanwhile, has struck a more equitable balance between its service tiers: it provides free-tiered users with an on-demand experience but only on desktops, whereas on mobile, these freeloaders can only listen to bands on shuffle. To hear a full album on a phone—which is where an increasingly high proportion of music streaming occurs today—users must pay. Spotify’s paid tier also removes advertising. According to sources with knowledge of the company’s strategy, Spotify has continually tweaked and adjusted these features in an effort to serve both casual and committed user bases without one group cannibalizing the other. The result is that 30 million of its 100 million users pay $10 a month—which is more than any other streaming service on the planet.

Fortunately for YouTube, it only needs to attract a small number of its billion users to sign up for Red in order to create a significant revenue bump. Again, just over 10 million U.S. subscribers generated $1.2 billion in revenue for the music industry last year.

However, given that Red basically replicates the functionality of its free service, except for the ads, many worry that most users who are addicted to consuming music on YouTube won’t be sufficiently incentivized to pay $10 a month for Red, while users who love music so much that they can’t abide interruptions by advertisers would probably prefer a service like Spotify or Apple Music or even TIDAL. These other services not only make music central to the experience and nothing else, but that is also well-positioned to offer exclusive content from the music industry’s biggest stars (as opposed to exclusive content from a woman who is obsessed with unicorns).

That leaves a very narrow audience for YouTube Red to target: fans who care enough about music to want to avoid advertisements, but not enough to join a service where music is the first and only priority. In a crowded space where other services are focused on providing a great music experience first, foremost, and only, many are left wondering why a music aficionado would turn to YouTube Red over these other services.

Moreover, according to conversations with those familiar with the matter, YouTube is still very bullish on advertising. Far from looking to supplant advertising revenue with subscription revenue from YouTube Red, the company expects free, ad-supported streaming to remain core to its business. From its perspective, the fact that ads aren’t yet a wildly lucrative source of revenue is a matter of patience. As more ad inventory moves from television and terrestrial radio to digital platforms, YouTube predicts that the revenue from free ad-supported streaming will increase in time. But if the recent data is any indication, it could be a very long time indeed. And as a subsidiary of the world’s most valuable company, YouTube can afford to be patient, even if many of its creators cannot.

Normally, when a new subscription service fails to catch on, there’s little for artists to lose. From that perspective, the success or failure of YouTube Red is a YouTube problem, not a musician problem. But it’s not that simple. Because as it stands now, YouTube’s free offering doesn’t just “cannibalize” YouTube Red, as one industry source put it. It’s potentially cannibalizing the entire streaming music space, and still leaving artists with relative peanuts.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(26)