Google wants to make JOMO happen

Our phones are making us unhappy—so much so that we’ve improvised all sorts of workarounds to break our addiction to the endless stream of information, games, and messages in our pockets.

Now, Google—makers of Android, the most popular mobile OS in the world—is stepping up to take some responsibility. The company is releasing its Digital Wellbeing kit to Pixel phones, starting today; it will arrive to all phones running the new Android P “Pie” operating system when it’s officially released later this year.

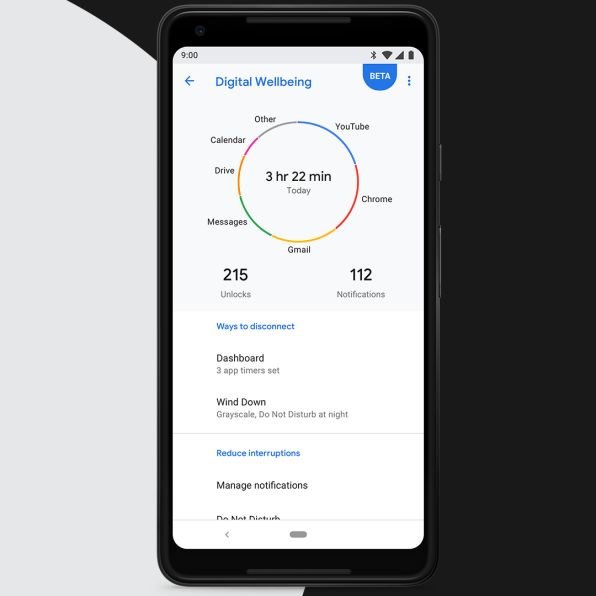

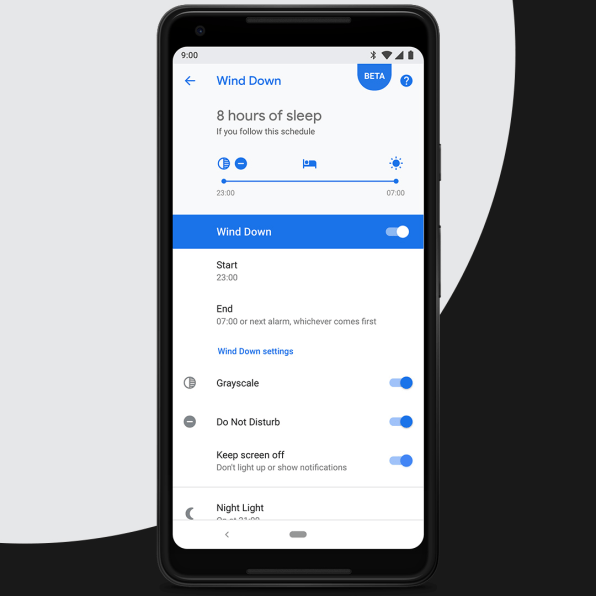

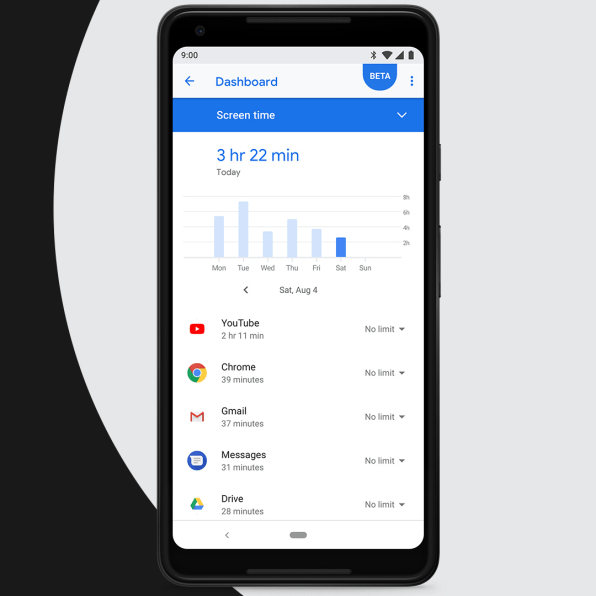

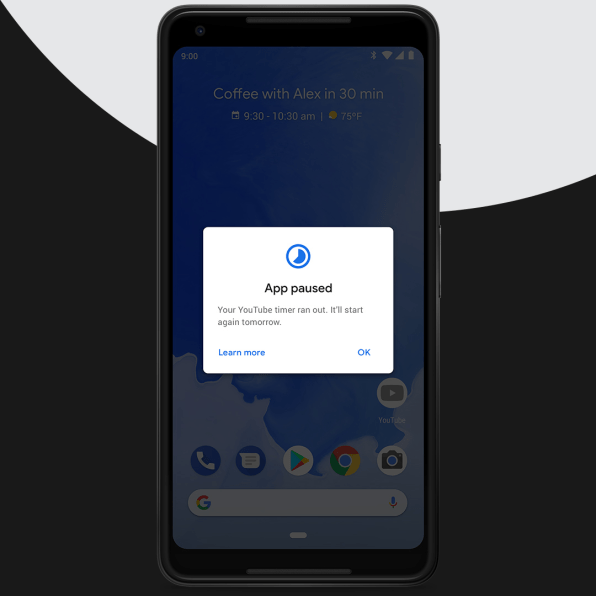

Digital Wellbeing includes metrics that let you see things such as the number of times you’ve unlocked your phone and the amount of time you’ve spent on it in a day. It also features interventions including a wind-down mode, which will slowly turn your screen a less appealing gray at night as you get ready for bed, and an app timer, which allows you to set personal limits on how long you spend inside apps such as Facebook.

The update comes at a time when Silicon Valley is just beginning to acknowledge its role in building addictive hardware and app platforms. Apple will have similar features in its upcoming iOS 12, and Instagram recently introduced a notification to tell users when they were all caught up with content.

To date, the more engagement that companies can get from users, the more they profit. But Google and others seem to recognize that users are on the cusp of digital burnout, and that short-term gains matter less than long-term industry health.

“The bottom line is that if people don’t love their phones, they’ll stop using them,” says Glen Murphy, Google’s Director of UX for Android and Chrome. “I think there could be short-term impact to a bunch of different metrics [after implementing Digital Wellbeing]. But we as a design team don’t pay attention to that because it would confuse things. We want to make sure the phone is something you are happy to keep in your pocket every day for the rest of your life.”

So, how do you remake the smartphone to keep all of its helpful features but curb our consumption? It’s like asking the snack industry how they create a potato chip that satisfies you with a single bite.

Building a healthier phone

Google’s designers have recognized that the smartphone has been taking too much of our attention for a long time. Android’s former head, Matias Duarte, who is now vice president of Material Design at Google, has joked to me in the past about carrying the transcendental weight of looking around, seeing people glued to their screens, and knowing that he was, in part, directly responsible for that. How do you even begin to solve the problem?

Google began by doing three years of research studies around the world. And whether in Sweden, Singapore, or China, the company heard the same thing: People were resentful of their phones. Behavior that the studies spotted in Japan was particularly interesting. There, a significant portion of the population had given up powerful smartphones for pared-down “feature phones,” without modern apps.

“It was interesting because they were all incredibly happy!” says Murphy. “There can be some bias there, but they all talked about how they saw everyone around them tied to their phones. Yes, they were missing out on some capabilities, but they didn’t feel beholden to their phones. They didn’t need to answer every message right away because they weren’t getting them right away.”

Google took this insight to heart. “What we’ve tried to do is bring that to people: the joy in missing out.”

The challenge is that we’re all already hooked on the phone’s never-ending stream of information. Email. Text messages. Slack. What Google learned in its research is that apps are part of the problem, but apps themselves aren’t the only things drawing us in. The more alluring component is the people who are using all these apps; it’s that our friends, family, or boss has communicated something we feel we cannot miss.

“If we hadn’t done that research, we would have focused on the app-to-user relationship, and would have created controls that weren’t as useful for people in dealing with their hyperconnection to one another,” says Murphy. That became a philosophical underpinning, and a filter, for the tools the company developed. Don’t just treat the app. Treat the person, and their relationships, inside it.

Additionally, Google designers were worried about the company’s own use or abuse of power. “It’s a hard one, because any action, even inaction, is making a statement about what we believe about user behavior,” says Murphy. “It’s like saying, ‘whatever happens today is fine!’ ”

From all of this, Google concluded that the first part of Digital Wellbeing had to be a sort of nonjudgemental user intervention. Rather than cut the cord to your friends on Instagram, Google created a snapshot of individual behavior. The company found that the average person was unlocking their phone 180 times a day, so they created an analytics page to show that. It’s a way of personalizing a fact we all know, to make it salient.

“Generally, whenever we said that number to people, they were like, ‘That’s just the kids with Snapchat. That’s not me.’ Then they look at their phone and say, ‘I use Gmail like my kids use Snapchat,’ ” says Murphy. “Creating those moments for reflection is really important for us. That’s where a lot of this has to start. We don’t want to be in a position where we’re bossing people, telling them how to use technology. We want to put people in a situation to reflect.”

Google wants to create awareness of user behavior, then give users the control to alter it—controls that go deeper than what we’ve had thus far.

An example is found in more statistics. Google found that 70% of people silence their phone’s ringer and notifications, but, by and large, they end up using the phone anyway. So now, within the Digital Wellbeing settings, you can add more options to “Do Not Disturb,” allowing you not just to mute notifications audibly but also to mute them visibly on the home screen. (That visual muting is on by default in Android Pie, too.)

“The overall mechanism is, make it so notifications are there, and you can get t0 them,” says Murphy. “But they’re not interrupting or distracting.”

What’s next

Are interventions like these enough? Is Google putting too much responsibility into users’ hands for their own health? I ask Murphy this: “Are you worried that Google could become the next Phillip Morris? And you’re just doing the equivalent of placing massive warning labels onto cigarettes that no one reads anyway?”

“Absolutely.” Murphy answered. “Historically in software, settings in products often fall into this category—’I can’t decide; let’s make the user decide.’ So you end up in this world where users are prompted constantly and they become blind to it.”

Ideally, Google doesn’t want to make Digital Wellbeing a destination that puts the onus on users, but a philosophy that sinks into the foundations of Android’s UX itself, grounding every decision the design team makes. A perfect example is the Android Pie beta features, where this approach is already available—again, in notifications. Swiping away certain notifications from certain apps repeatedly over a number of days eventually causes Android to inform me that I’ve been dismissing these a lot, before asking if I’d like to block them.

It’s an imperfect solution—and Murphy agrees. I swipe away all sorts of notifications, like Gcal meeting alerts, that are absolutely vital to organizing my day. But it cuts to Google’s challenge in promoting Digital Wellbeing: Now that we’re so deeply entrenched in the digital world, the company cannot simply turn off the stream. It needs to help us find the balance, and learn to predict and respond to our intent. It’s a challenge that Google built into its products this year, but there’s no end in sight for the company. The solutions will require artificial intelligence and machine learning, the perfect user prompts and sometimes no prompts at all. And, at least in the immediate future, it will require our own willingness to change our habits and to not override the tiny blockades Google, or Apple, put in the way of getting our next fix, because Silicon Valley will never cut us off from its own meal ticket.

“We’d love to get to a point where we use this phone as a mechanism that helps you enjoy life,” says Murphy. “If we can make it an invisible conduit to the joyful parts of your life [we want to]. Yes, that’s a long way off.”

(9)