How Darth Vader became the most iconic evil figure in film history

I remember the first time I saw Darth Vader in real life. It was in a department store. He was going up the escalators escorted by two stormtroopers, I was going down. For some reason I failed to comprehend at the time, the sight of him made me poop thermal detonators. It was completely irrational–he was just a very tall man in a costume, I was a 30-year-old. But a new Nerdwriter video essay may explain why my heart stopped when I saw him.

Evan Puschak–who took the Nerdwriter pseudonym when he started his YouTube video essay series on film, politics, music, painting, poetry, culture, and sociology topics back in 2011–explains how Darth Vader became cinema’s most famous icon of evil not by looking at the physical aspect of his existence–the design of his suit, stature, voice, and even his breathing–but by analyzing how Vader was framed, lighted, and shot. These factors were an essential part of the visual design that elevated the character to his status of archetype of cinematic evil.

Puschak starts with a very simple statistic to demonstrate the overwhelming power of Vader’s presence: in the three original movies, he only appeared for about 34 minutes of the total six hours and 28 minutes. That’s just 8% of the original trilogy footage and yet, it seems like he is everywhere.

The Nazi helmet and the skull of evil

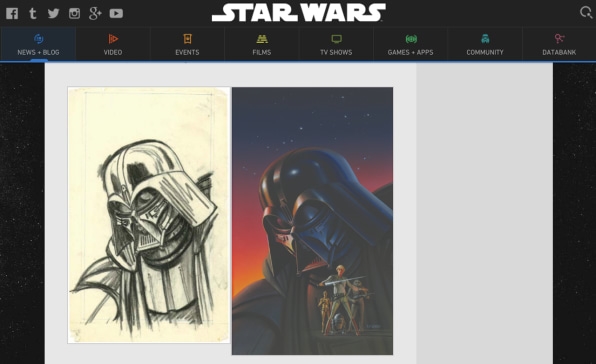

The physical design of Darth Vader was envisioned by legendary American concept designer Ralph McQuarrie and modeled by British sculptor Brian Muir. McQuarrie, who was a kid during World War II, figured out years later that he may have been unconsciously inspired by the German combat helmets and gas masks that deeply impressed him at the time. But originally, Vader wasn’t going to look like a robotic SS general. In an interview published in Star Wars Insider #76, he explains how Star Wars’ universe creator George Lucas originally “wanted a costume that would flutter on the wind, sort of a dark guy in a black cape with a big helmet, like a Japanese warrior–maybe with black silk over his face or something like that.”

But when he was sketching him, he figured out that the script had Vader crossing from his spaceship [which later became an Imperial Star Destroyer] to the Rebel Blockade Runner carrying Princess Leia and the Death Star plans–floating through space. “I thought ‘Gee, Darth Vader has to function in a vacuum,’” McQuarrie recalled at the time, “so I suggested to George that [Vader] might have some sort of spacesuit to enable him to survive this trip through the vacuum, and George said, ‘Well, okay, give him some kind of a breathing apparatus.’” That breathing apparatus became an evil skull mask, with a narrow chin and pointy cheekbones, the Nazi helmet framing it all over two dead glass eye sockets.

His character sketches, which were completed by a high-tech armor and a black cape, made Vader an obviously nefarious demon. But while McQuarrie imagined “a little, hunched, evil, ratlike person,” it was Muir who turned his design into an imposing figure, someone who would fill the screen not only representing villainousness but power incarnated.

Muir’s 3D reinterpretation was in fact so powerful that it eclipsed his entire life of work, as told in his book In The Shadow of Vader. His figure became so iconic, Muir said in a 2016 interview, that the rest of his work–from the Space Jockey on Alien, 10 James Bond movies, and four Harry Potter films to the original Indian Jones trilogy, Superman, Guardians of the Galaxy, Thor 2, and Captain America–won’t change the fact that he is and will always be known as The Guy Who Sculpted Vader.

When you inhabit that menacing inert helmet and suit with David Prowse’s 6.5-foot frame–the actor who played Vader–and James Earl Jones’s thundering voice, you get something extremely powerful. But is that power enough to become the most famous incarnation of evil this side of Satan? As Puschak explains, it is not. The last factor of Vader’s nefarious equation of badassery lies in the films themselves.

The shiny dark side

The Lord of the Sith’s malignant nature was instantly drawn in one single shot in A New Hope, when his dark figure walks into Leia’s pristine white Corellian corvette. As he walks slowly inspecting dead bodies lying the floor, everyone understands that this guy is definitely the nemesis of any heroes that may come later in the film. His unique dark silhouette would, in fact, define his entire presence on screen through the entire trilogy like nothing else.

But in Episode IV, Vader isn’t at the height of his power. It’s as if Lucas didn’t really want to focus on him, making it appear more or less as Grand Moff Tarkin’s loyal Doberman. In most shots with Peter Cushing–the actor who plays Tarkin–Vader appears behind him, sometimes half cut by the frame and sometimes completely out of focus. Gilbert Taylor, Episode IV’s cinematographer, discussed with Lucas about how terrible Vader looked against the first version of the Death Star dark grey sets. It was so bad, in fact, that he and Lucas had the set designers cut lighting holes on the walls and ceilings of the Death Star so Vader’s pure black body could have some highlights and contrast on screen (this was the reason why the design of imperial installation uses all those distinct white light grids made of rounded, interlocking vertical segments). Still, in medium shots, Vader appeared ethereal, like a phantasmagorical figure set against dark shadows. In close-ups, Puschak points out that Vader helmet appears “dirty, smudged, and used” following Lucas desire for a “documentary look.”

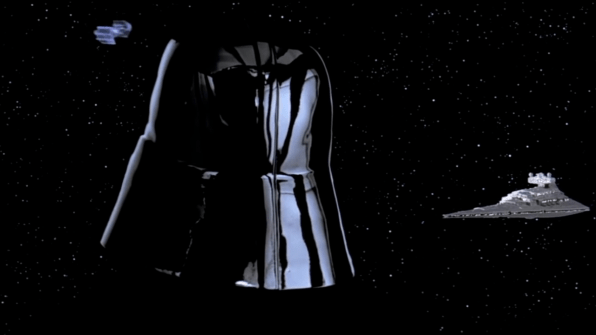

That changed completely when director Irvin Keshner and cinematographer Peter Suschitzky took the reins of the Star Wars universe in Empire Strikes Back. It was then when Darth Vader became the incredibly overpowering evil character that we know today. Instead of weathering his suit, Keshner and Suschitzky decided that the helmet and his armor had to be really polished, so much that it looked “as smooth as volcanic glass” on screen. You can clearly see this from the very first shot of Vader in the film: Looking through a window of his Star Destroyer, Vader looks into the blackness of space. Black against black, and yet, you can clearly see him, all reflections, texture, and shape.

The Nerdwriter points out that Keshner and Suschitzky realized that Vader became more menacing the less naturalistic he looked. The more polished and unreal he is, they figured out, the more he looks like the embodiment of pure abstract evil.

But it didn’t stop there. In Empire, Vader became the central figure. The framing of his body, with every element on screen gravitating towards him or framing him, the constant use of his unique silhouette, the lighting, the ultra-sharp look in each shot–everything combined to push Vader to the height of his power. In Empire, every kid–including my 8-year-old self at the movie premiere in Madrid–was scared of his dark (father!) presence. We all understood Luke’s primal fear because every single frame with Vader in that movie was terrifying to us too. Not terrifying in a screaming horror film kind of way–although that scene in Dagobah, with Luke venturing into the cave to find Vader in the dark made me shudder–but in a profound, irrational way that stayed deep inside you.

Or so it did for me. A little bit more than two decades after watching Empire in a movie theater, that irrational terror stored in my inner child came out in the form of an instinctual fight or flight response–making my heart go out of my mouth and putting me on guard at a stupid department store. A practical demonstration of the visual power of this icon of evil. “Impressive. Most impressive,” indeed.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(58)