How Living On Jane Jacobs’s Favorite Block Changed My Life

I never knew how great I had it until it was gone.

From 1998 to 2005, I lived in a charming, rent-stabilized one-bedroom apartment on the third floor of 560 Hudson Street between Perry and West 11th in Manhattan’s West Village. It was cozy and warm with brick walls, an occasionally working fireplace, and views on a garden courtyard. When not working for a few different publications in Midtown offices, I spent more than half my time in that place, ensconced at my favorite table at the coffee shop across the street, and getting a burger and a pint at the White Horse Tavern up the block.

In that apartment, I recovered from the emotional trauma of the breakup of my first marriage, recuperated from the shock of having the South Tower fall on top of me on 9/11, found my voice as a writer, learned to negotiate a better salary, had my first (and only) piece published in The New Yorker, bonded with good friends over pasta dinners to watch The Sopranos on Sunday nights, and courted the love of my life.

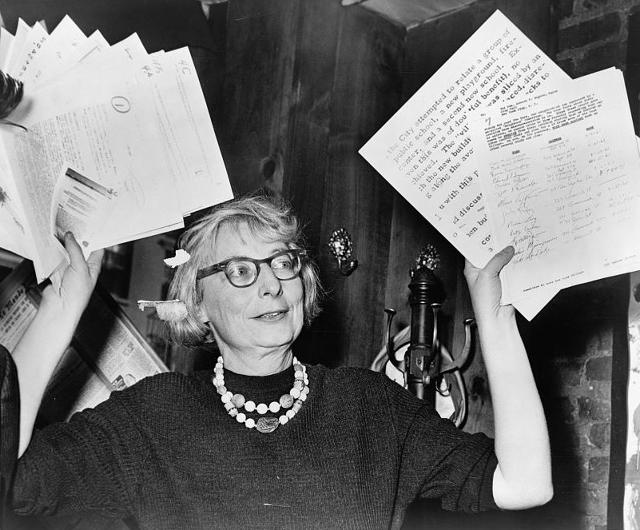

Only later, a few years after I moved in with my now wife in Park Slope, did I learn that my block was the inspiration for one of the most influential urban planning books of all time, Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Jacobs, who died in 2006, would have turned 100 today. (You’ve probably already seen the great Google Doodle to honor her.)

With that iconic book, written in 1961, Jacobs basically invented the idea of urbanism, that cities could be inspiring and uplifting places to live. Her call to action was revolutionary in impact—after decades of rapid population growth in cities marked by looming skyscrapers, old buildings torn down to make way for highways, and the retail boom in supermarket chains that decimated small mom-and-pop shops. For Jacobs, the rebirth of cities lie in neighborhoods, that even a metropolis as sprawling as New York City was really just a collection of neighborhoods with their own traditions and character and community.

Jacobs wrote the book while residing in a three-story townhouse at 555 Hudson, directly across the street from my old apartment. The experience of living on that block in that corner of New York City—from kids playing on the sidewalk and neighbors planting flowers to local butchers getting lunch and the fruit man selling her an apple—made her realize that it offered a way forward for Americans struggling with an often-impersonal modernity. Even the sidewalks of our neighborhood inspired her:

Under the seeming disorder of the old city, wherever the old city is working successfully, is a marvelous order for maintaining the safety of the streets and the freedom of the city. It is a complex order. Its essence is intricacy of sidewalk use, bringing with it a constant succession of eyes. This order is all composed of movement and change, and although it is life, not art, we may fancifully call it the art form of the city and liken it to the dance—not to a simple-minded precision dance with everyone kicking up at the same time, twirling in unison and bowing off en masse, but to an intricate ballet in which the individual dancers and ensembles all have distinctive parts which miraculously reinforce each other and compose an orderly whole. The ballet of the good city sidewalk never repeats itself from place to place, and in any once place is always replete with new improvisations.

Almost 50 years later, when I lived there, the neighborhood really hadn’t changed much. Most of the buildings were the same, including my tan-colored building (circa 1900). Aspiring novelists and college students (though the longshoremen were long gone) still occupied the red benches outside the White Horse Tavern, where I remember watching the Red Sox clinch the playoffs in 2004 and getting free beers for lunch from a friendly bartender. Instead of execs and “business lunchers” crowding Dorgene restaurant, I would get sashimi at Sushi West. The Lion’s Head coffeehouse had moved but I spent endless hours reading and getting breakfast at Panino Giusto, often entertained by celebrity sightings, like Lou Reed and Laurie Anderson getting frittatas for brunch with their terrier Lolabelle. (At one point, I plotted with the coffeeshop’s manager to open a wine bar together around the corner on West 11th Street, but the tiny space and high overhead were too daunting.)

It was my whole world, that block. Though I didn’t know many of the neighbors in my building (typical for NYC), I befriended others on the block who became my community. The guy at Village One Stop would talk to me about politics every morning that I bought a Times. The waiters at the Italian place comped me free meals and let me borrow some of their pots and pans when I threw a dinner party. The old Village artist used to regale me with stories about Jackson Pollock and Ellsworth Kelly smoking dope and getting into fistfights with romantic rivals. The owner of the stationery store loaned me money to hire a locksmith when I forgot my keys and was locked out of my apartment. On the night of the blackout in 2003, a local waitress and I drained a bottle of wine and lay down in the middle of the street to look at the stars. One snowy morning, I walked outside and found that some sanitation workers had tied my bike to the top of the bus shelter to save it from the jaws of their snowplow. On humid nights in July and August, I used to go to the roof with a ratty blanket and sleep like the dead.

That block was a microcosm of the world—you could live your whole life without having to leave. From food and drink to romance and gossip, you didn’t want for anything. Though I never knew about its role in history, I always had a sense that it was special. To this day, about once a year, I wander over to the neighborhood, get a spring in my step when I step on the cobblestone streets and gawk in envy at the townhouses with the capped-dormer attics. If it’s a chilly evening, the smell of wood burning in fireplaces fills the air. It’s changed a bit in the last 10 years–-more chain stores and fancy boutiques, and the rents have skyrocketed—but it’s still unique. And I get deeply nostalgic with every return visit.

Maybe one day, I’ll return. Not that I can afford it anymore.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(21)