How The ACLU Is Evolving To Fight Trump In Streets Not Just The Courtroom

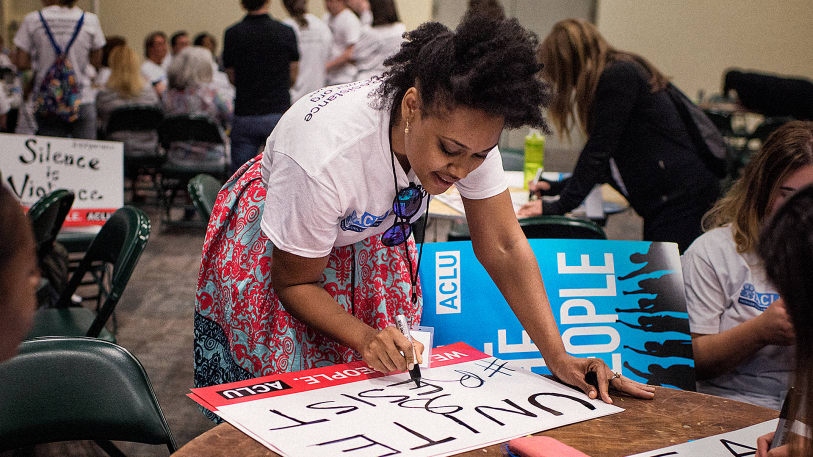

When President Donald Trump arrived in Nashville on March 15 to stump for his new health care and school reform polices at the city’s Municipal Auditorium, he was greeted by something unexpected. Several hundred protestors waving signs were already marching through town against him.

That uprising wasn’t really supposed to happen. Anti-Trump forces had learned of the trip just a day or two earlier, and on short notice, grassroots organizing is difficult: Rallies generally take time plan and have to come together through lots of decentralized chatter. (There’s the flurry of Facebook and web-page posts, phone trees, even fliers). The Nashville effort, however, was plotted differently. An organizer tagged the upcoming event to a map within the a new political action platform called People Power. As others learned about it, they RSVPed their interest and were kept in the loop via whatever kind of communication they preferred, including up-to-date blasts from text messages.

People Power, which is backed by the ACLU, launched just days before on March 11. It represents a proactive move for the nonprofit civil rights group, whose primary mission for the last hundred years has been to challenge discriminatory practices, policies, and actions in court. In addition to defending people’s rights when they are violated, the group is now hoping to enlist more people to lobby for the rights of others in ways that could lead to policy or law changes that afford people more civil protections before they get targeted.

Fiaz Shakir, the group’s national policy director, says that because the current administration is enacting sweeping changes that could lead to widespread civil rights concerns, like foreign travel bans and mass deportations for undocumented workers, it was time for their own countermeasures to evolve. In fact, their supporters expected it.

“After the election we saw that people were rushing to the ACLU with their financial contributions and with their e-mail address sign-ups to tell us that, you know, ‘Tag you’re it: You’re the leader of the resistance movement,’” Shakir says. “The most common question I was being asked was, ‘What can I do, and how can I do it with others to help?’”

The result is something he calls “Organizing 2.0”: On People Power (site logo: several fists raised in unison) anyone can sign up to plan or volunteer for an event. By doing so, they also share their contact information, which allows the ACLU to notify them of events that are happening in their immediate area. Each event is plotted on public map, which lets people join more nearby efforts, and organizers figure out what other organizers they might want to contact to join forces. Anyone who registers for the service can add an event. An internal team at the ACLU then reviews what’s being scheduled; it will reject anything with offensive language or partisanship. Not everything needs to be a direct action. “Our goal is that the platform be used as a tool for all grassroots groups and actions that work toward resisting the Trump administration’s attacks on our civil liberties,” notes a spokesman in an email to Fast Company. That includes more mundane coffee-talk style “meet-ups” for activists to mingle and learn more.

“We asked everyone to meet with their local law enforcement officials to discuss whether this city is going to be a welcoming city, a freedom city, or not,” Shakir says. Their publicly posted blueprint includes guidelines for how to interact with officials to ensure each meeting request is legitimately considered and responded to appropriately.

That’s a lot different than attending a march. “That’s kind of a high bar . . . There’s a lot going on there,” Shakir admits. When done on a city-by-city basis, however, it has the power to create national change just as powerfully as federal mandates. Such places would be telegraphing their status as safe havens, assuring those who live there that no local order-keepers will be participating in blitzkrieg tactics. By extension, the policies limit ICE’s and CBP’s access to both the local man power and facilities that they’ve come to rely on to carry out some missions. “I think it has the most meaningful impact,” he adds. “I’m honed in on the question of what could really change the way Donald Trump conducts business.”

To create the platform, Shakir tapped members of both the Bernie Sanders campaign and President Obama’s former White House tech team. More than 200,000 people are now active on the platform, and in roughly two weeks have planned at least 500 events. Most are Freedom Cities-related–a meeting with the sheriff of Harvey County, Kansas, for instance, or another with a representative of the Oro Valley Police Chief in Arizona. The trickier part will be maintaining that momentum. Sanders, who used similar tactics in his presidential bid, was asking people to rally around a single person (himself) with an immediate, singular goal (to be elected). That’s different than asking people to back a cause group that represents multiple issues that aren’t easily resolved.

In reality, what the ACLU has built works more like a political social network. The platform is designed around individuals promoting those events that matter most to them–it’s not ACLU specific. Shakir expects representatives from other groups like Indivisible and Move On to advertise actions there too, which would bring in more supporters to collaborate on efforts where their ideals overlapped. In the near future, the ACLU plans to add functions that will let event hosts build and maintain their own RSVP lists, and communicate directly with other hosts within the platform to speed up how they can combine forces.

In the meantime, the ACLU will be continuing its policy-driven change strategies. “While I would say we’re going to focus on calls to action that are consistent with the ACLU’s mission, we are also opening up the platform of People Power for you to submit events of your own choosing. And we’re not going to try to discriminate there,” Shakir adds. “I would say the value of the platform is A) that it’s active, and B) that it’s targeting like-minded people.’”

(38)