How to keep your data from brokers and marketers

We’ve seen a stream of revelations about data brokers in recent months, and though the stories vary, the takeaway is consistent: Our privacy has never been more vulnerable.

In May, Vice found that data brokers have been collecting and selling location information of people visiting abortion clinics. That same month, Human Rights Watch revealed that most edtech companies are collecting information on children. And earlier this year, comedian John Oliver famously showed how easy it is to target and compile embarrassing information on members of Congress.

Even a conservative estimate by Privacy Rights Clearinghouse puts the number of data brokers in the U.S. at over 500. And the information they collect is vast, although details about it are scarce. In a 2014 article in MediaPost, an executive at one of the largest data brokers, Acxiom, said that, “For every consumer we have more than 5,000 attributes of customer data.”

Experts say there is virtually no regulation of this data collection industry in the U.S. “Within the law, anyone could be doing pretty much anything with your data,” says Bennett Cyphers, a staff technologist at the Electronic Frontier Foundation. “And they don’t have to tell anyone about it.”

There are, however, ways to fight back against data tracking. The first step is knowing how—and where—you’re being tracked.

Public records

Data collection begins at birth. Your birth certificate provides the first personal information put out to the world. Over the years, local and state governments and the federal government publish records telling your life story: Census data, motor vehicle registration, property ownership, marriage licenses, voter registration, bankruptcy filings, divorce proceedings, professional licenses, court cases, criminal convictions, and at the end of your life, a death certificate.

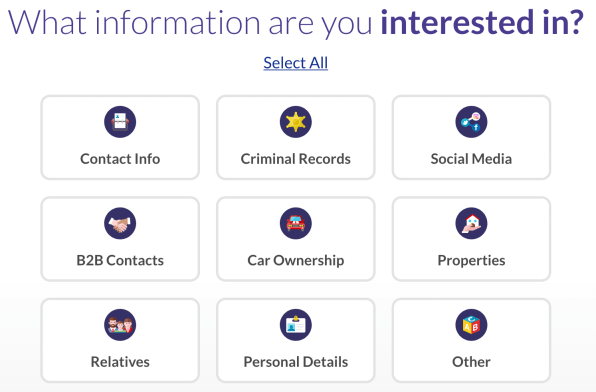

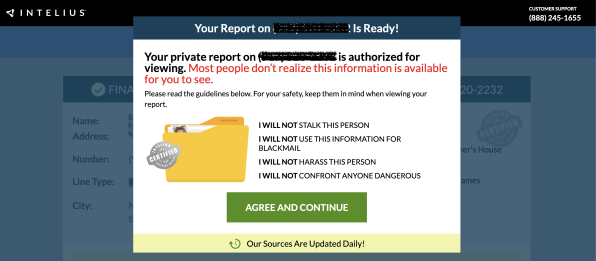

These documents are the primary resource for so-called “people search” data brokers such as Intelius and Spokeo. (They also search online data, such as social media.) You can use those services to, say, reconnect with a long-lost friend, or to confirm a business associate’s legitimacy. But a corporate entity—or worse yet, a stalker—has access to those same tools.

I decided to test these services, using one of my relatives as a guinea pig. Spending $26.89 on another people search site, BeenVerified, I found accurate information on their age, current and past addresses, property ownership, phone number, spouse (and three-dozen other family members), neighbors, and “associates”—all with links to their own profiles. (There were also criminal history and bankruptcy categories, but nothing juicy.)

What you can do

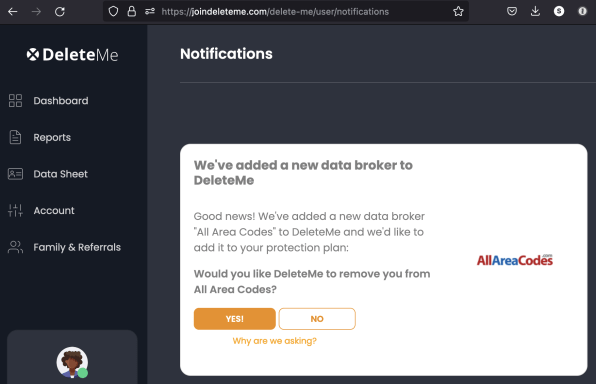

You can get the same results for free by contacting each major data broker (DeleteMe provides free tutorials), but it’s tedious. DeleteMe lists 587 brokers it tracks, and from which it requests data removals.

Purchase history

Beyond public records, peoplefinders.com also buys information that consumers have provided to companies—for instance, purchases recorded when you swipe your store loyalty/rewards cards.

This kind of information gathering extends beyond people search sites and is a staple technique in the vast realm of marketing and advertising data brokers. By knowing your purchases, they and the partners they sell data to can offer discounts or hype other products that their algorithms reckon you will like.

Keep in mind that pharmacies offer loyalty cards, allowing data brokers to track over-the-counter medical purchases such as vitamins and skin creams. Information about prescription drugs should be protected under privacy provisions of the HIPAA health law, says Emory Roane, policy counsel at the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse. However, “we’ve seen data brokers get access to that information from pharmacies before,” he says. Whether from prescription or OTC purchase, this information feeds a large subset of advertising data brokers that specialize in health information (both from purchase histories as well as internet browsing around medical conditions and medications).

With loyalty cards, you at least get something (lower prices) in exchange for your data. But often companies offer no such sweetener in return. According to direct marketing company Exact Data, its 2,000-plus sources include magazine subscriptions, purchase histories, memberships, and attendee registries. In addition to the monetary price of a product, service, or event, you may also pay a hidden surcharge with your personal information.

“There’s a lot of data brokering happening, not just with who we consider third-party data brokers . . . but also among the people and brands that we’re customers of,” says Rob Shavell, CEO and cofounder of DeleteMe’s parent company, Abine.

In order to see what data is collected, I started investigating my own life. I pay T-Mobile $85 per month for unlimited calling, texting, and cellular data. I also pay with “all personal data we collect and use when you access or use our cell and data services, websites, apps, and other services,” per the company’s privacy notice. They may use this data to (emphasis mine) “advertise and market products and services from T-Mobile and other companies.”

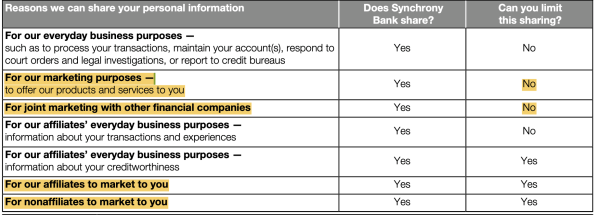

Then I checked my paper mail and found a credit card offer from Synchrony Bank. The company’s 10-page service agreement informed me that Synchrony may use my personal data to market to me directly, together with other financial companies, through affiliated companies, and through nonaffiliated companies such as retailers and direct marketers.

It’s a generally accepted truism that, with free services like Facebook or Google, you pay in personal data. But even when you put up hard-earned cash (for purchases or interest charges), you’re also paying in data.

What you can do

For loyalty cards, consider whether the money you save is worth the privacy price. You may want to selectively use your cards: perhaps OK for buying a bag of chips, but not for purchasing hemorrhoid cream.

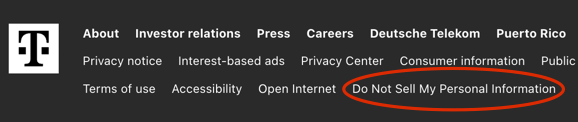

Many businesses now offer at least partial data-collection opt-outs, thanks to the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). Though the law is only binding for California residents, many companies extend CCPA rights nationally. You often find a link to this opt-out at the bottom of websites under the phrase “Do Not Sell My Personal Information.”

T-Mobile, for instance, has a CCPA option, but it’s arduous, requiring you to provide a copy of a driver’s license or passport and a photograph. Synchrony Bank lets you limit affiliate and nonaffiliated marketing, but not other types of itself and other financial services.

Credit history data

I likely got that offer from Synchrony Bank (and many others) due to my good rating with credit reporting (aka consumer reporting) agencies such as Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion. They can help a bank assess someone for a loan or help a landlord decide if a tenant can pay the rent.

These companies also use their vast information stores (on $27 trillion, over 45 percent, of all U.S. consumer invested assets, says Equifax) to target customers for financial or other offerings. Equifax, for example, states plainly in their privacy statement: “We collect, use, and sell personal data as part of our consumer and commercial marketing services. This includes providing customers [meaning data brokers and marketers] with personal data of potential customers [meaning you] to inform their marketing efforts.”

What you can do

Like many other data collectors, credit-reporting agencies provide the CCPA opt out of data sales. You can also visit OptOutPrescreen.com to stop credit card and insurance offers.

Web-browsing data

As you’ve likely heard, small text files called cookies hang out in your browser and allow marketing companies to follow your web browsing. Cookies work in conjunction with tracking code, often in online ads. For instance, if a Google ad appears on multiple sites, the tracking code in each ad can check the Google cookie to record that the same person (technically, the same web browser) has visited each site.

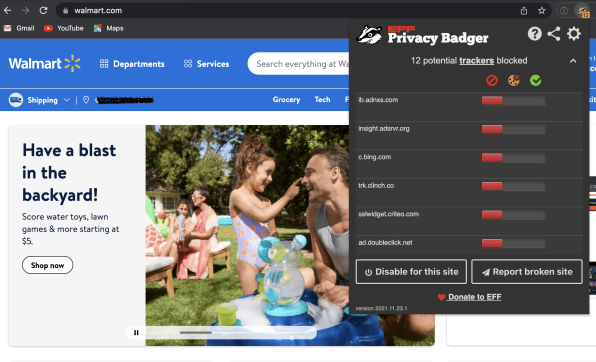

To appreciate how pervasive this is, I installed the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s free Privacy Badger browser plugin. When I viewed the top 25 U.S. websites (per Similarweb) Privacy Badger found: 5 potential trackers on eBay, 7 on The Weather Channel, 10 on CNN and ESPN, 12 on Walmart (demonstrating retailers’ data surcharges), and 29 on Yahoo. Further down the popularity list, journalism sites are rife with trackers. Privacy Badger found 15 on the New York Times and 24 on Fast Company. (This is not an exact science: Privacy Badger often returned different results for the same site.)

Some of the biggest names in Silicon Valley—including Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Oracle—are behind this tracking. Google and Facebook are the largest online advertising companies in the world, by far. Not only do they track you on other sites, but they have you as a captive audience on their own pages.

Unlike people search companies, advertising data brokers claim to collect only anonymized data, identifying a person not by a name but by some token such as a cookie ID or a hashed (mathematically scrambled) version of your email address. However, it is often trivial to link these profiles back to real people,” says Cyphers, “either by using context (like geolocation data identifying a person’s home and work) or working with another data broker who can link anonymous IDs back to emails or names.”

What you can do

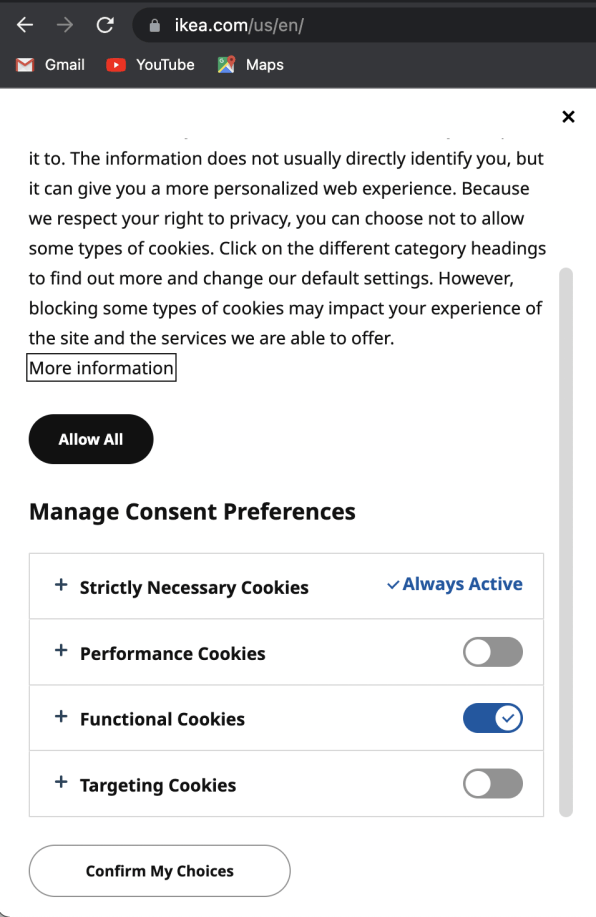

Thanks to the European Union’s General Data Protection Act, many sites now provide an alert about cookies. They typically feature a prominent “accept” button, but some include a link to settings that let you disable most cookies.

That can get exhausting, however, so there are some other tools.

Some web browsers—including Brave, Mozilla Firefox, and Apple Safari—can thwart tracking cookies. Take Firefox: Instead of allowing an advertiser like Google to place a single cookie that it can reference from every Google tracker-equipped site, Firefox tricks Google (or another advertiser) into setting a new cookie for each site. The upshot: You look like a different person to every site you visit.

You can also install a tracker blocking extension like Privacy Badger, or uBlock Origin. Those products are especially useful if you’re a devotee of Google Chrome, which lacks the cookie-busting tools of Brave, Firefox, and Safari.

To further limit Google’s tracking, try the privacy-focused search service DuckDuckGo. If you can’t quit Facebook, you can still reduce the information you provide.

Mobile app trackers

Ever more online interactions are not in a browser, but through apps on phones and tablets. And apps have access to trackers far more powerful than cookies—a mobile device ID called IMEI or MEID that’s unique to each gadget. Phone operating systems also provide an Identifier For Advertisers (IDFA), which is exactly what it sounds like.

Many apps also track your location—whether or not it’s necessary. A study by security firm Avast, for instance, found dozens of free Android flashlight apps that access location data. And like their computer-based counterparts, mobile browsers are subject to cookies and tracking code.

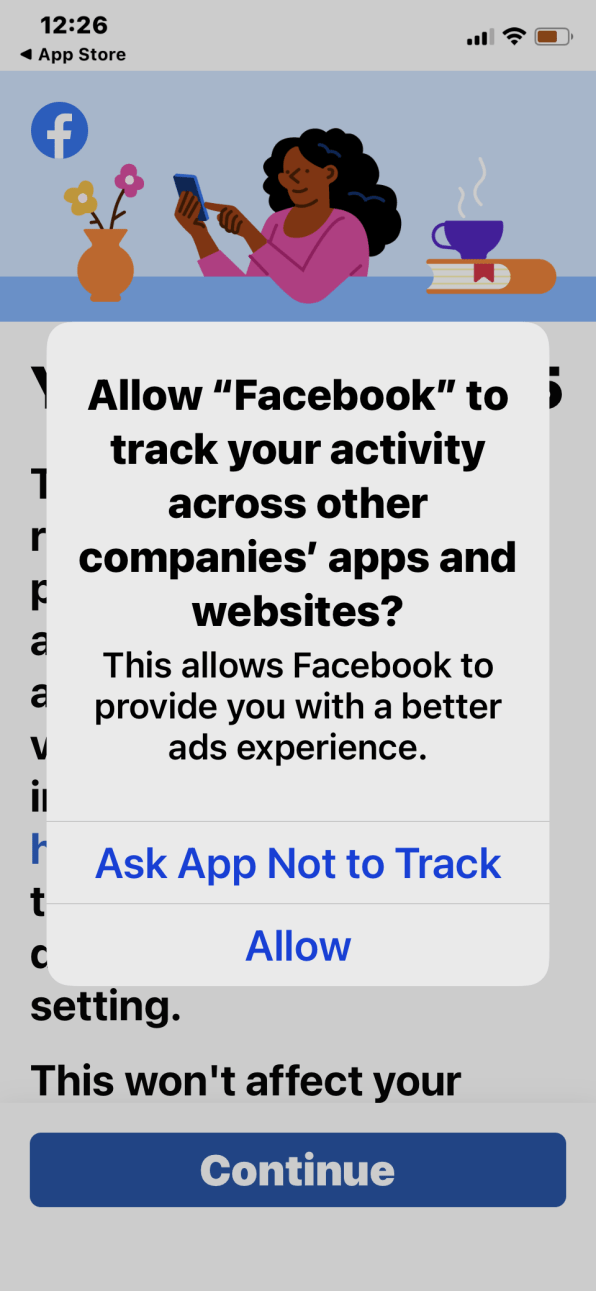

What you can do

Protections against mobile tracking greatly improved when Apple introduced App Tracking Transparency in iOS 14.5. If you select “Ask App Not To Track” during installation, iOS will not share your Identifier For Advertisers, and it instructs the app to forgo any other type of tracking. The best proof that this is working: Facebook parent company Meta announced that Apple’s policy would cost the company about $10 billion in lost advertising revenue this year. Google is following suit: Starting with Android 12, you can simply delete the phone’s Advertising ID.

On the mobile browser side, you can use a version that blocks trackers, such as Safari on iOS devices, or Mozilla Firefox Focus.

The biggest players

Beyond Google and Facebook, there are a number of other data broker heavyweights, including Acxiom, Epsilon, Oracle Advertising (previously Datalogix), and the big credit-monitoring companies: Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion. An Acxiom promotional video provides an example advertising target: homeowners with income over $200,000, in a neighborhood with homes averaging $300,000-$500,000, who drive an SUV, have high school-aged children, and travel for leisure more than twice per year.

Acxiom’s main business is helping clients manage, organize, and clean up the data they already have, says chief privacy officer Jordan Abbott. But it also collects public information and licenses data from smaller brokers. Abbott says that Acxiom vets providers and assesses how Acxiom and its clients will use the data. “That privacy impact assessment is designed to tease out the potential risks to consumers and mitigate . . . the risk as much as we can,” he says.

The dangers of giant data brokers became clear in 2017, when Equifax announced a data breach that exposed the personal information of 147 million people. Then in 2021, Epsilon was fined $150 million for knowingly providing data to companies that sought to defraud older Americans.

What you can do

Because they are so big, it’s worth visiting each of these companies to request removal of your data. Privacy Bee provides free instructions.

If you use DeleteMe, you can request to have these companies added to your plan. (They are not included by default.)

Will government help?

You may be asking: Why should I have to do all the legwork, or pay for a service like DeleteMe? Can’t the government do something about this?

Some states are making progress on that front. Along with the CCPA, California has a law requiring all data brokers to register with the state. It follows a similar registry in Vermont. Together, these two registries include about 540 companies. “We are only getting the slimmest glimpse into this landscape,” says Roane, the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse lawyer. He notes a new study by the blog Martech that found 9,932 marketing technology companies.

Bills in states including Delaware, Massachusetts, and Oregon would require similar registries. Massachusetts would also include the right to “opt out of the processing of the individual’s personal information for the purposes of the sale of such personal information.”

At the federal level, a bipartisan draft bill called the American Data Privacy and Protection Act would create a national data-broker registry and a “Do Not Collect” mechanism that allows a consumer to submit a single request that goes to most registered data brokers. (It excludes consumer reporting agencies, which perform legitimate background checks and are regulated by the Fair Credit Reporting Act.)

But legislation is a slow process, often derailed by powerful interest groups and political infighting. So, while we hope for comprehensive protections, limiting exposure to data brokers may remain our personal responsibility for a long while.

TL;DR: 12 ways to thwart data brokers

(12)