I Came Up With A Creative Idea, Someone Else Just Did It, & I’m Still Recovering

It finally happened.

Since the turn of the century (which sounds even longer ago than it really is), I’ve been harboring a secret. It’s an idea for a creative project that I’ve been keeping to myself all these years, not sharing it with anyone—not even those closest to me—for fear of having someone else steal my concept. Every few weeks, I even Google terms that describe the idea, just to make sure that no one else on the planet has done it. Every time, I breathe a sigh of relief and go back to daydreaming about a way to make my idea a reality.

Until last night. At one in the morning, just before going to sleep, my head nodding with fatigue, I checked my Tweetdeck to see if there were any interesting news stories I could flag for Fast Company’s morning writer. And there it was: “Can you guess these movies from their long-exposure photos?” It was a link to a story about a London sculptor named Jason Shulman who had set up his camera to take a single photo of an entire movie. He’d made beautiful long-exposure photos of movies ranging from Citizen Kane to Fantasia that looked like dream states, colors drifting and blurring with faint shadows and shapes, like some mysterious corner of the Milky Way.

I bolted wide awake, panic coursing through my veins. That was my idea! Someone somewhere on this planet had the same lightbulb go off in their brain and they went out and executed my idea. My mind was spinning. I shouted into the night. I punched the wall. I paced the living room, cursing myself like a madman. And I couldn’t fall asleep for hours, my head pounding and my heart aching with regret and envy.

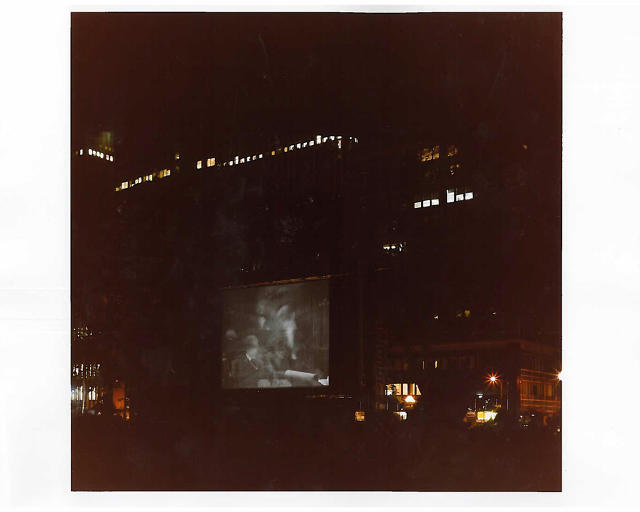

You see, back in 2001 or 2002, when I was taking a class at the International Center of Photography in New York City, I became fascinated with long-exposure photography. I would go out in the middle of the night with the medium-format Minola Autocord that I bought for $65 at J&R Camera, set it up on a tripod, open the shutter all the way for about a minute, and get amazing images of the swirl of city life against the still life of storefronts and buildings. On one of my outings, I came across an outdoor movie screening at Bryant Park of an old silent film. The energy of the black-and-white movie against the backdrop of Midtown skyscrapers was striking and I took a few long-exposure photos.

And that’s when the lightbulb struck—why not keep the shutter open for 90 minutes and capture a photograph of an entire movie? Sure, it may end up being a mush of black and brown, but it also might be magical. All the stories in a single movie—the dramatic moments, car chases, conversations, love scenes, quiet moments of reflection—captured in a single image. Those tens of thousands of frames capturing a myriad of shapes and colors and lights distilled to a single photograph.

Over the next few days, I embarked on my creative journey. At first, I set up my tripod in my apartment, played a movie on TV, and experimented with different shutter speeds (20 seconds, 45 seconds, 1 minute, 5 minutes, 10 minutes) with the aperture closed down as much as possible. I rushed to the darkroom at the ICP to develop the negatives and they were all overexposed. Obviously, the picture tube was emitting way too much light.

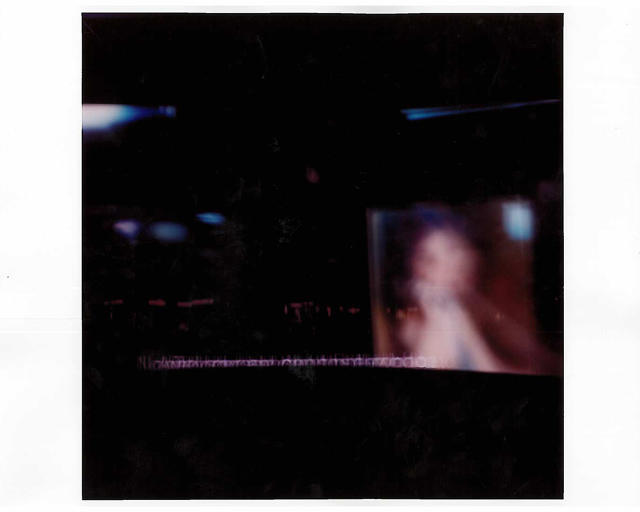

So, I pivoted and focused on movie theaters. Knowing that it was illegal to record a movie, I snuck my tripod and camera into a movie theater in the middle of the day, when it was relatively quiet. Setting up my tripod next to me, I saw matinees of Jodie Foster’s claustrophobic thriller Panic Room and the Mexican classic Y Tu Mama Tambien, and conducted the same shutter speed experiments. The images that I developed were interesting—some of them were overexposed, others were double-exposed silhouettes and faces, and some were glorious medleys of light and energy.

I was elated, but I still wanted to figure out how to successfully take a picture with the shutter open as long as two hours, or an entire movie. And that would take more research. I went to B&H and Adorama and talked to camera experts to try to find the right lens filters and gels. But nobody had a good answer, and I didn’t have the budget to spend hundreds of dollars on different filters that may not have worked.

And this was all a hobby for me. My full-time job was working as a journalist. I didn’t have the money to really dive into this project—and I was terrible at setting goals and fulfilling them. So, I went back to my regular life, caught up in life changes, from marriage and fatherhood to new jobs and friendships.

But I always thought about “my idea,” clinging to it as protectively as a mama bear around her cubs. I would fantasize about taking a few months off to get the right filters and borrowing the large-format Hasselblad at ICP, crunching the numbers that would help me realize my dream. And I daydreamed about the movies I’d love to film, from old classics like L’Atalante and Breathless to big-budget pics like The Fast and the Furious and The Dark Knight.

And I never told anyone (maybe once I whispered it to my wife in a careless moment). Not even my best friends or family members or shutterbug friends (two of whom would have been amazing collaborators since they owned dozens of cameras and knew all about filters). I wasn’t paranoid that they would steal my idea but rather that they might mention it at a dinner party or in casual conversation and give someone else the concept. And so, my somewhat compelling idea for a photography project turned into a state secret that required CIA tactics to protect. I was obsessed with this vain desire to be the first one to unleash this amazing idea upon the world, deluded by the fantasy that it would get a big gallery show and bring me money, power, and respect. Did I mention the money?

Obviously, you’re not crying for me. I had a decent idea but then I didn’t execute it for more than a dozen years. So I have nothing to complain about. It’s all on me. Stop whining and get over it.

All true, but I’d still like to figure out what happened to me. Because it’s a bit of a pattern. There have been other ideas, both creative and professional, that I’ve never followed through to completion even though I was enthusiastic about them and knew that they would succeed. Back in the late 1990s, I brainstormed with friends about getting a food truck in Manhattan and serving quality panini and salads along with lattes and cappuccinos (that was back when the only food trucks in the city served hot dogs and kebabs on skewers). We found some partners, researched the prices of trucks, equipment, and food supplies, and thought of potential names for our business. It never happened: I got caught up in my day job, my partners moved to L.A. A few years later, the food truck revolution took off and stormed the planet, serving everything from foie gras donuts to Korean gochujang burgers with kimchi and Sriracha mayonnaise.

Other stillborn ventures: opening a coffee shop/wine bar in the West Village, attaching a GoPro to a pigeon while it flew around New York City, opening pop-up bookstores to feature upcoming and struggling writers.

None of them got off the ground. I know it’s an experience that many of us have had: You come up with an idea, think about it, obsess over it, maybe even start to work on it—and then you drop it. Is it just laziness, or is there something more psychologically complex going on? For me, it feels a little self-destructive. I’m afraid of failure and all the resulting shame. So I unconsciously sabotage my creative projects to avoid even risking that failure.

It’s a phenomenon that has been explored by many artists and writers over the years, from Jhumpa Lahiri to C.S. Lewis. I’ve talked about it with my father-in-law, Richard Toft, a painter in Virginia. He often works in egg tempera, a traditional technique of mixing ingredients to create paints that can add months to the time it takes to create one of his beautiful landscapes. To combat the self-destructive instinct, he keeps a quote often attributed to Goethe by the drafting table in his studio:

Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back—concerning all acts of initiative (and creation), there is one elementary truth that ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans: that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then Providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in one’s favor all manner of unforeseen incidents and meetings and material assistance, which no man could have dreamed would have come his way. Whatever you can do, or dream you can do, begin it. Boldness has genius, power, and magic in it. Begin it now.

Such an amazing quote. I’ve printed it out and taped it to the wall by my desk at home. But obviously it doesn’t always work. Other things get in the way of the creative process: lack of money and time, fear, insecurity, the latest episode of Game of Thrones. And then the frustration kicks in; I joke that my butt is black and blue from kicking my own ass all the time.

Another question: Why did I become so competitive? So what if an artist pursued the same idea that I had years ago? (And yes, I admit that on some level, this essay may be some attempt to prove that I was the true pioneer.) Why can’t we both make long-exposure photographs of movies? I have nothing but praise for Shulman’s images, which are stunning. His long-exposure photo of Fantasia is so alive and gorgeous it belongs in a museum. We’re not in competition. It’s about having a creative idea and then going through the messy and energizing process of realizing that dream and putting something beautiful out into the world.

Or that’s what I tell myself. (Because you know I’m going to punch the wall again tonight.)

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(9)