In 100 Years, $77 Billion Worth Of San Francisco Property Could Be Underwater

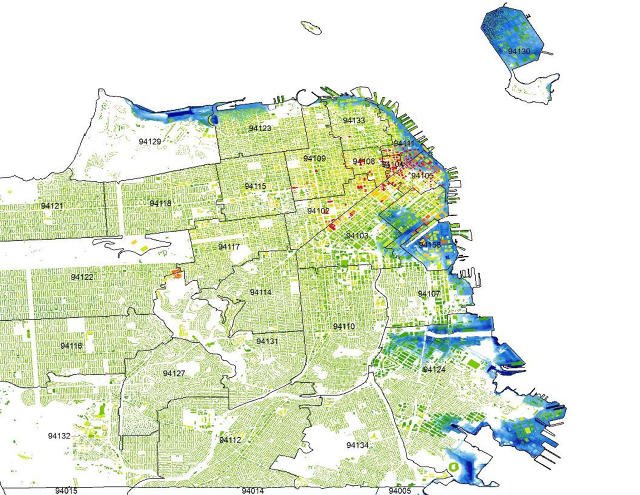

By the end of the century, some of San Francisco’s million-dollar apartments and multimillion dollar houses will be underwater. A recent report calculated that property worth a total of $77 billion is at risk from rising seas in the city.

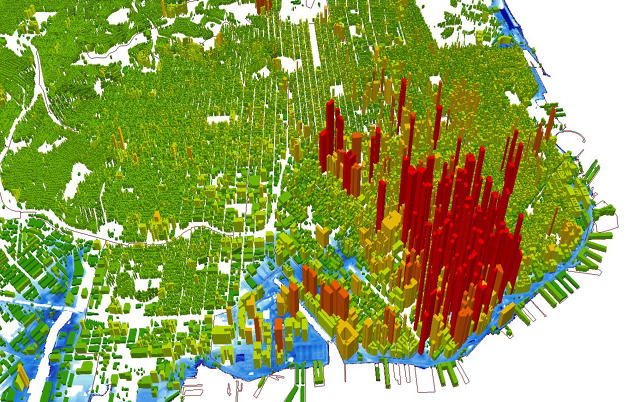

“We developed a digital map showing how much property would be in the bay, as opposed to what’s on land today,” says Paul VanderMarck, chief strategy officer at Risk Management Solutions (RMS), the company that mapped out the risk for the city.

In the past, RMS focused on modeling different types of risk, such as earthquakes, for the insurance industry. Now their business is shifting to a new problem: helping coastal cities figure out how to deal with changing coastlines.

In San Francisco, the city is creating a new action plan that will be based on a worst-case scenario of 5.5 feet of permanent sea level rise, plus another 40 inches of temporary flooding from high tides and heavy rain.

The city considered various scenarios, but decided to base its plans on the most possible flooding that’s likely to occur. “In general, [scientific] models have been underestimating what’s happening,” says VanderMarck. “If you set plans for how you’re going to build buildings and sea walls and protect infrastructure—and you invest billions over decades, and then it turns out that your estimates of sea level rise were too low—then the implications for cost are very significant.” Not to mention the people living there.

Around the city, more than 200,000 commercial and residential buildings—along with major infrastructure like the airport—are at risk from either temporary flooding or permanent loss due to sea level rise if the city does nothing to prepare. Even more dangerously, the risk extends well inland, and isn’t limited to property directly on the coast.

Armed with the new maps, San Francisco is currently creating a strategy to try to save as much property as possible. “It’s almost inevitable that, in the end, the plan will be a combination of multiple approaches,” says VanderMarck. “One approach in some areas will be to surrender to the fact that seas are rising—it’s impractical, either economically or for other reasons, to try to defend against that in certain areas.” In other places, the city may build higher walls or other defenses.

In the Ocean Beach neighborhood, for example, it’s likely that the city will reroute portions of the road that’s currently along the water, replacing some areas with open space, while also building up dunes and protecting some infrastructure like a wastewater tunnel. On Treasure Island, where the city is planning to build a new sustainable community, any new housing will be set back from the water, with parks along the edges—parks that very likely will be reclaimed by the bay.

RMS now plans to create similar risk models for other cities around the world. “A lot of cities, they don’t know what the risk is that they actually face,” he says. “For a coastal city, it’s clear that you have some exposure to sea level rise, but it’s hard to formulate public policy if you can’t actually quantify what the nature of that exposure is.”

Eventually, the same tools might be used to help homeowners decide if they should invest in a house near the coast. “A lot of people assume by the time they sell the house, it still will be a distant enough risk that it won’t affect the market value of the property,” he says. “But at some point that isn’t going to be true anymore.”

Have something to say about this article? You can email us and let us know. If it’s interesting and thoughtful, we may publish your response.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(7)