Lemonade Is Using Behavioral Science To Onboard Customers And Keep Them Honest

Insurance startup Lemonade won itself headlines in January with the boast that it had successfully approved a claim in just three seconds. In that time, Lemonade’s software had run 18 anti-fraud algorithms and sent a payment to the lucky customer’s bank account—a process that would have taken a traditional property and casualty insurer days, if not weeks.

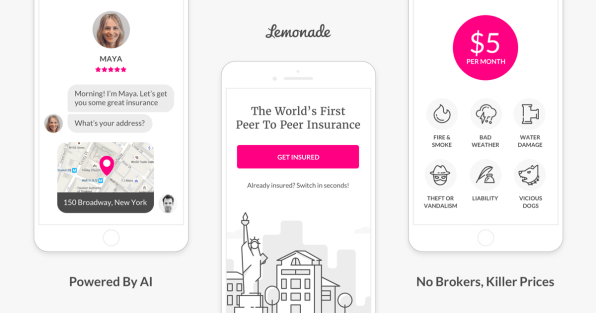

But it’s what happened before Lemonade’s artificial intelligence kicked into gear that makes the renegade insurer so potentially disruptive to this trillion-dollar industry, for which premiums alone comprise 7% of U.S. GDP. The customer, Brooklyn educator Brandon Pham, opened Lemonade’s mobile app, signed an “honesty pledge” to attest to the truth of his claim, and then recorded a short video explaining that his Canada Goose parka, worth nearly $1,000, had been stolen.

That deceptively simple claims process is the byproduct of academic research on psychology and behavioral economics conducted by Dan Ariely, one of the field’s most prominent voices and Lemonade’s chief behavioral officer. For example, Ariely’s work has demonstrated the power of priming—hence the very deliberate decision to have customers like Pham sign their name to a digital pledge of honesty at the start of the claims process, rather than at the end.

“There’s a lot of science about when people behave and misbehave that has not been put to use,” says Lemonade cofounder and CEO Daniel Schreiber. Some of that science would suggest design tweaks like signature placement; other ideas are more fundamental to Lemonade’s B Corp business model, like the decision to donate surplus premiums to charity. If customers are invited to direct leftover premium payments toward a nonprofit of their choice, or so the thinking goes, they will be less likely to cheat on their claims (surveys suggest that 1-in-4 Americans would pad a claim with no compulsion).

Lemonade is even applying behavioral science to itself, publishing unusually transparent blog posts that include data on customer growth, bank account balances, and more. The posts bolster Lemonade’s nice-guy reputation—but also serve as a reminder that the New York-based company, which is currently licensed to sell rental and homeowner insurance, is still young and teeny-tiny, despite raising $60 million in venture funding. (Lemonade processed and paid out just six claims worth $4,589 in 2016, including Pham’s.)

“They’ve raised a lot of capital, there are big expectations,” says Nabil Meralli, a founding partner at London-based InsurTech Venture Partners. “The potential and certainly the brand that is behind it have been strong.”

To succeed, Schreiber and cofounder Shai Wininger will have to scale a technology platform that is already leaps beyond the paper-pushing norm at industry stalwarts like Allstate and State Farm. But they will also have to prove that they can meaningfully lower customer acquisition costs and reduce fraud through the application of behavioral theories. Incumbents have history—and a $6 billion collective marketing budget. Lemonade has (experimental) science.

The fintech world is watching closely. Behavioral economics has developed a loyal following, with companies large (JPMorgan Chase) and small (savings app Digit) hiring specialists to help design their products and customer interactions. Digit, for example, increased its users’ short-term savings rates by 51% by asking if they would like to direct their tax refund to savings before the cash windfall landed in their account.

The field’s central thesis: “We shouldn’t blame humans for our failures in complex decision making. It’s on the designers of the system,” says Kristen Berman, cofounder, with Ariely, of Common Cents Lab, a nonprofit lab based out of Duke University.

That foundational belief has led behavioral scientists, who combine aspects of economics and psychology, to explore topics like happiness, honesty, and perceived value. These days, a behavioral scientist might find job openings in education, health care—even at Airbnb. But it is the financial sector where the field has its deepest roots, and perhaps its widest adoption.

“A lot of behavioral economists saw the [2008 financial] crisis coming. People are paying more attention to [the field] because they were right,” says Ryan Falvey, managing director of the Financial Solutions Lab at the Center for Financial Services Innovation (CFSI). Falvey has partnered with consultancy ideas42 to help startups in CFSI’s lab learn how to incorporate behavioral research into their product design. Ideas42 is also involved in reviewing the lab’s applicants, further encouraging founding teams to take a Lemonade-like approach.

“The companies doing this well realize that you need to set up a platform from the beginning to test out insights,” says Josh Wright, an executive director of ideas42.

Both he and Berman, of Common Cents, distinguish between A/B testing, design thinking, and the more rigorous approach that behavioral science implies.

“Designers pay attention to the details a lot, we love designers,” says Berman. “But I’ve never been to a meeting where a designer says, ‘I’ve read a literature review’ on a topic.” Similarly, she argues that data scientists running A/B tests can miss the forest for the trees. “Numbers can tell us some things, but they can’t really tell the whole story. People make decisions in context, not based on absolutes.”

At this stage, with limited available claims data, the best proxy for Lemonade’s mastery of behavioral techniques is its onboarding process. Since launching last fall, the company has been growing its policy count at an increasing rate, with 2,230 customers as of January. Roughly 1-in-4 people who get a quote from Lemonade’s bot go on to purchase the renter’s or homeowner’s insurance they have been offered. The bulk of those customers are Manhattan renters, the majority of whom did not previously have insurance of any kind (Lemonade takes care of canceling existing insurance on the customer’s behalf, if necessary).

“It was the most seamless experience,” says Marc Mouhadeb, a real estate entrepreneur who read about the company at launch in the New York Post, says of his onboarding. Even better: After Lemonade canceled his Allstate policy, he got a check in the mail for the premium balance. Mouhadeb was so enthused about the product that he talked it up at a dinner party, which is how a mutual acquaintance connected him to me.

Lemonade has a knack for inspiring that kind of response. Jon Zanoff, who runs Empire Startups and sees fintech demos by the dozen, has himself become a convert. “There’s a risk with fintech companies who assume millennials don’t want fantastic service, they’re looking for technology,” he says. “What Lemonade does well is it makes the service frictionless. As a user, when I had a next-level question [during sign-up], it was a completely seamless transition to the support staff.”

Zanoff argues that insurance companies, perhaps even more so than banks and other financial institutions, are vulnerable to startup challengers. “Insurance companies really fell in love with the perception that they were very risk averse,” he says.

Lemonade, in contrast, is led by “fail-fast” technology entrepreneurs. Schreiber, a lawyer by training, has spent the last 20 years working in consumer electronics, cybersecurity, and hardware. Wininger previously founded Fiverr. They have hired senior staff from incumbents like AIG and Liberty Mutual, but are committed to a different mode of operating.

“There’s this black hole, a way of doing things that everyone tries to bring you back into. ‘You can’t do X,’ ‘that’s the way it’s always been done’—that’s the black hole speaking,” Schreiber says. “We haven’t yet got to a velocity where we can ignore the black hole. We have to be constantly mindful and vigilant.”

Lemonade has applied for licenses to operate in all 50 states, and expects to be available to 90% of U.S. consumers by the end of the year. Property and casualty, although the least regulated sector of the insurance industry, still requires dealing with significant red tape, state by state. Of course, there’s a reason for those rules, designed to ensure that insurers are capable of managing risk and paying out claims on a catastrophic scale.

Other insurtech startups are going after the same set of consumers. Last year, the sector attracted $1.7 billion in venture capital, according to CB Insights. Some incumbents reckon that startups could snatch 20% of their business over the next five years.

If Lemonade is among those winners, it would represent a major proof point for behavioral science—and for Schreiber, a Nudge reader and self-described “Ariely groupie.”

“There’s something called the Ulysses contract,” he says, in reference to Homer’s iconic Sirens episode. “Your future self is not as transparent as your present self would like to be.” He points to Lemonade’s “transparency reports,” and its business model overall. “We’re no more honest than the next guy, but we have tied our hands.”

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(156)