MAGA is a superbrand. Cutting off Trump’s social media isn’t enough

After the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, many have been quick to blame social media, hoping that that insurrectionist communications could be thwarted by shutting off accounts and access. These actions may slow the spread of lies, hatred, and propaganda. But unfortunately, banning digital communication about insurrectionist ideals does not ban the ideals themselves. It’s a deeper and more complex process.

One problem with technology access bans is that they address how messages are carried, but not how their content originates, which is in the hearts and the minds of those who have adopted them. Ideals can be transmitted through messages and calls to action, but are formed via fantasies of alternate realities drawn from the past and future imaginings. Addressing these core beliefs is where change must occur. This involves dismantling the ideals that the insurrectionists have created and adopted, as well as the mechanisms they use to distribute those messages.

The insurrectionists that attacked the Capitol on January 6 were cloaked in various brand symbols. Some of these symbols were tattooed onto bodies. Others were worn on shirts (with special ones printed for the occasion), caps, fake fur pets, or as face paint. Some people carried flags and weapons. They arrived on buses and planes and stayed at hotels or Airbnbs in the area. And on that day, they woke up, dressed themselves in their gear, and went to rally, riot, and reverse the election results.

At first, the insurrectionists seemed to be engaging in cosplay, alternately on a mission, field trip, and photo shoot as they wandered through and pillaged the Capitol. New symbols were produced: a flag here and there, a photo on the dais, feet on Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s desk. One participant absconded with Pelosi’s podium.

The man seen carrying House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s lectern during the US Capitol riots has been arrested, according to a law enforcement official. https://t.co/87hiLWNvof

— CNN (@CNN) January 9, 2021

In the wake of the spectacle, some observed that the insurrectionists were “doing it for the ‘gram, for the brand.” What’s missing in this analysis is just how much the idea of “brand” matters. This taps into the past decade of my research on groups, branding, and how branding defines all of us in more ways than we would probably care to admit.

In my 2016 doctoral dissertation, “Disrupting Silicon Valley Dreams: Adaptations Through Making, Being, and Branding,” I explored two ideas. One is that the mechanisms underlying brands act as a basis for people forming groups and limits their choices to conform to group norms. The second is that these norms are communicated as a hybrid: Both brands and messages together carry information about ideals, and stopping one will not stop the other.

People have many different brand and identity symbols they affiliate with. Those affiliations and the stories behind them are impervious to dissolution by the shutting down of one particular online service or another. They are baked into the symbols that people adopt to represent their affiliations—the brands. That’s what enables the stories that form these ideals (or the interpretations of them), which in some cases originated centuries before social networks were in the picture.

“Paul Davis, a Dallas-area lawyer, was fired on Thursday from his position as associate general counsel and director of human resources at Goosehead Insurance after a Twitter user posted his Instagram story.”: https://t.co/oVRgJF68ZA

— Pamela Newkirk (@ptnewkirk) January 9, 2021

As I wrote in my disseration, “branding provides a way of addressing the emergence of certain factions in communities. This becomes particularly clear with Internet groups because for the most part there is little else to point to as a basis for formation and action; the members of the group just do not have enough locational or other bases for coordination to account for the level of cohesion that arises, while most people will have many different brands to base relationships on.”

The insurrectionists weren’t only doing it for the ‘gram, they were doing it because they had been instructed to do so, through a brand and brand story that incited them to storm the Capitol. While they were incited by many different groups online and in person, their chief brand was MAGA, and their chief brand officer was Trump.

MAGA caps weren’t just about ‘making American great again’ (whatever that means).

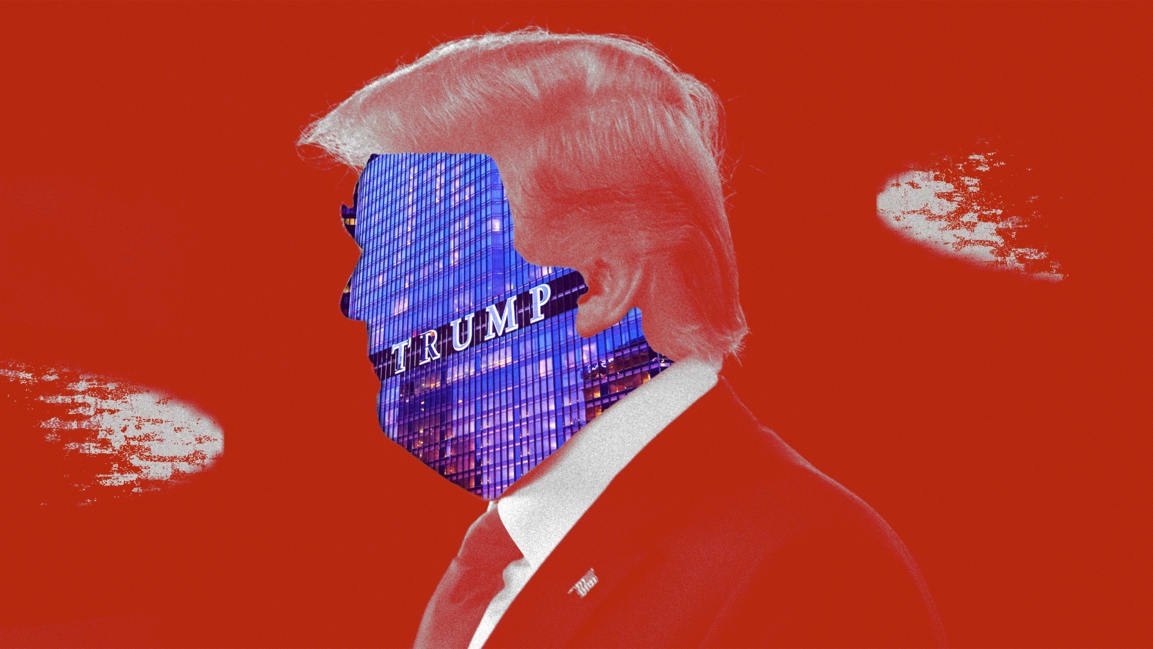

Donald Trump has based much of his life and presidency on branding. His brand is gilded, serif font, BIG, shiny, golden, and green (like money). But if you scratch underneath the surface, worn-out scaffolding is underneath.

The gift shop at Trump Tower sold neckties, candy, pens, cups, scarves, tote bags, and much more, both turning a profit and keeping Trump in the public consciousness. But wasn’t just small things that Trump branded, it was big things like buildings. As his career in real estate faltered, he moved to branding himself through books, TV shows, and more. Each instance was a photo opportunity, a way to leverage one big branded item for another opportunity down the line. This is what he built his presidency upon, and this is what has sustained him and his followers.

When Trump moved into the White House, it didn’t appear that he was ever interested in the actual government operation headquartered there. He was seemingly interested in the representation of the White House, what it meant as a symbol in the American mind. From all appearances, he didn’t really want to be President. Instead, he wanted the brand mindspace of the presidency and the profit that it could generate.

Trump’s followers are also obsessed with brands—they cover themselves with symbols and have created brand stories from various failed movements throughout history that invoke rebellion and discord. These followers already had their own brand affiliations before Trump came along, and the MAGA brand story he sold to them was a superbrand that subsumed their core values found in the other brands they’d collected, such as victimhood, being strong bad boys, and optimism under fire.

Some people with little in the way of education, morals, or both gravitated toward the brand, More educated, affluent people who wanted to feel a bit on the “bad boy” side added Trump to their identity brand portfolios, too.

Wednesday afternoon, demonstrators-turned-rioters, many carrying pro-Trump signs and wearing MAGA hats and other indicators of support for Trump, broke through the doors. Some of them came to blows with U.S. Capitol Police…https://t.co/dMICI2p1wW pic.twitter.com/lF6Ig3jpv3

— Jim Geraghty (@jimgeraghty) January 7, 2021

Trump sold all of his followers a brand that extended beyond his golf courses, gilded apartment towers, and steaks. MAGA caps weren’t just about “making American great again” (whatever that means); they were brand symbols for horrifying and inhumane movements in the present and throughout history. Those caps were, and still are, symbols of a dangerous superbrand.

Additionally, Trump told his MAGA followers that he was the only reliable source for news and information, and that everything else was “fake”—that is, that the only trusted brand was Trump’s. He gutted the institutions that were the foundation of American life, because the way he constructs and values brands is to make them shiny on the outside and ignore their contents. This extended to signature campaign issues such as building the wall, which just needed to be big enough for photographs to power the Trump brand.

The Trump brand infected people who didn’t even believe in him or like him. Many of us spent the past four years defending ourselves and our institutions from this steamroller of a branding initiative that devalued everything that wasn’t a photo-op.

When a market gets oversaturated by a brand that can’t sustain its leadership, people choose other brands.

Trump’s brand story culminated in the Capitol insurrection. The idea that the insurrectionists could take what they wanted through brute force—including the election—was a programmable algorithm delivered over the past four years and at last week’s rally. Since the insurrectionists had been fed the idea that they could do that, and they watched the president do it for four years, of course they were going to try it.

When the insurrection failed—and Trump grudgingly decried the violence, once it served his interests to do so—there was a quick series of angry online posts from people describing how they’d been “played” by the president. But they were also played by themselves and all of the other brand ideas and mythology they’d adopted. “Make America Great Again” wasn’t ever true. It was just a way for Trump to connect his followers to the nostalgic brands that they had already affiliated with in order to tap into their brain and heart space.

What the insurrectionists didn’t realize was that collectively, their gathering formed another monument for Trump to leverage. His metrics were the crowd size that his followers formed, how they looked, and how he could parlay that size into the next big thing. He even tried to use the square footage of crowds at his Georgia rallies as proof that Joe Biden could not have won the state.

The future of the Trump brand

In the wake of the Capitol storming, Trump was finally cut off from his social media presences by Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat, and numerous other platforms. But decreasing the distribution of a brand’s messaging is not enough to kill it. The damage done by the Trump brand is going to stop when the product that it represents goes bad or becomes unpopular. This is not necessarily decided by Chief Brand Officer Trump, or by his critics, but instead by the consumers of the Trump brand.

When a market gets oversaturated by a brand that cannot sustain its leadership position, people will likely choose other brands. For Trump’s brand, which requires ever bigger things to leverage, there are few places to go once he’s been President of the United States and failed to be reelected. Trump tanked his brand, and may not have a post-presidency plan for his brand downshifting.

In permanently suspending Trump’s account (and his 88.7 Million followers) Twitter has deprived Trump of a major avenue for monetizing the presidency after he leaves office. Those howls of rage you hear coming from the White House are about $$$, not free speech.

— Susan Hennessey (@Susan_Hennessey) January 8, 2021

Social media and the websites that hosted Trump’s brands were a major enabler of Trump’s funding and helped him trade on his name and brand for goods. They are abandoning him. Even the PGA has had a change of heart for 2022, moving its championship away from a Trump course.

The Trump brand moving to the bargain bin still leaves the rest of us to deal with his followers and their commitment to their own brand portfolios, some of which include explicit symbols of hatred. Even if many of them spend less time on social media in their leader’s absence, they are still connected to each other by the brands they’ve adopted. As always, new names and new brands will emerge that will form groups and use the internet in similar ways. Even Trump seemed to be trying out a potential brand pivot with his post-impeachment video statement, in which he called for peacefulness from what he referred to as “our movement.”

Or perhaps they can find a better brand. Going forward, all we can do is create brand messages that are reality-based and good for us. In a video message, former movie barbarian and California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger offered a tempered steel sword as a unifying metaphor and symbol of strength as a counter brand and message, though many of us could do without the weaponry no matter how well-intended.

What we need now is to create new brand stories of recovery, hope, joy, peace, prosperity, health, and goodwill towards each other, and to find symbols that better reflect these values and the deeper story they could contain. If we can find a broad market for those ideas, we may get to a much better place than where we’ve been.

S. A. Applin, PhD, is an anthropologist whose research explores the domains of human agency, algorithms, AI, and automation in the context of social systems and sociability. You can find more at@anthropunk and PoSR.org.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(6)