No Internet, No Credit Cards, No Problem: How Airbnb Launched In Cuba

Cuba runs on cash and almost no one has easy access to the Internet. But Airbnb found a way to beat U.S. hotels to the market nevertheless.

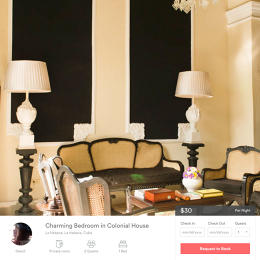

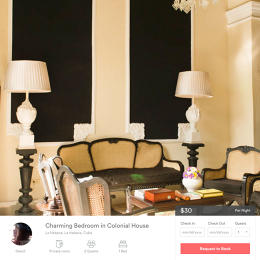

If you don’t know much about Cuba, Airbnb’s recent announcement that it has begun booking rooms there sounds pretty unremarkable. After all, Airbnb operates in more than 190 countries, and its offerings are as diverse as they are plentiful. In the “castles” category alone, there are more than 600 possibilities. Cuba is hardly its most exotic locale.

But consider this: Cuba has, according to Internet freedom watchdog Freedom House, only about a 5% open Internet penetration rate, or access to Internet not controlled by the government. And its economy still runs almost entirely on cash. The idea of Airbnb—a company that provides an online marketplace for housing and processes digital payments—catching on there sounds almost absurd.

How did such a digitally driven startup launch in a country where most people have no daily Internet access and no bank account—and with more than than 1,000 hosts, no less?

The answer to that question starts long before Airbnb launched—in 1997, according to Ted Henken, a professor at Baruch College who wrote a book about entrepreneurship in Cuba.

That’s when Cuba officially began regulating the industry of bed and breakfasts that had popped up after the country legalized self-employment in the early 90s. Called “casas particulares,” bed and breakfasts in Cuba have marketed themselves mostly by word of mouth (Henken, for instance, keeps a list of them that he shares with friends traveling to Cuba). The government also provides decals for casas particulares so that travelers can locate them after they have arrived in Cuba, and has made recruiting customers for the bed and breakfasts a licensed profession.

Meanwhile, lists like the one Henken keeps have found their way online to, he says, “little versions of Airbnb” that look like this site and this site. Given that few Cubans have access to the Internet in their homes, many casas particulares use middlemen with Internet access to communicate with future guests. “Like an Internet cafe for hosting,” says Molly Turner, Airbnb’s global head of civic partnerships.

And that brings us to December 2014, when President Obama ordered the restoration of diplomatic relations with Cuba, including removing some travel restrictions.

Airbnb had previously blocked would-be Cuban hosts from listing on its site. Now, it was about to become legal for them to do so.

The hurdles were not small: In 2011, the country’s National Statistics Office and the International Telecommunication Union estimated that about 22% of Cubans have Internet access, but that included people who only had access to a government-controlled Intranet. Until 2008, Cubans were banned from buying their own computers. Meanwhile, having a bank account is uncommon. “It’s not just that people prefer cash,” says Henken, “It’s almost the only way. People don’t trust anything else, at least not yet.”

Thankfully for Airbnb, however, it didn’t have to start from scratch. It simply tapped into an existing network of middlemen.

The company partnered with a handful of what it describes as “Internet cafes for hosting” that were already facilitating bookings online. These small businesses already had connections with most of the homes for rent on the island, and already charged them a fee for management services. Now they will handle Airbnb listings. Even for hosts who have bank accounts, Airbnb needs to work with intermediaries to deposit funds into their accounts. For the many hosts without access to bank accounts, it partnered with third parties who, in some cases, will deliver cash to their doorsteps (Henken says Airbnb is likely using an established money transfer service to handle payments to unbanked hosts, Airbnb declined specify who’s providing the service for them). All of these are informal partnerships.

Airbnb taught these middlemen how to use the website, and helped them add information. “Maybe they didn’t have high-quality photographs in their homes,” Airbnb’s Turner says. “Maybe their availability was written on paper and not kept online anywhere. Our team did a lot of work behind the scenes talking to hosts and making sure that the information was up to date and current.”

But for the most part, Henken says,”What Airbnb is doing is formalizing, monetizing, and really announcing [casas particulares].”

That’s not a small thing. Keeping it legal is tricky at this point. Turner says she “gut checked everything” with the U.S. government. Could Airbnb hire a Cuban photographer? (yes). Could it publish photos taken by a Cuban photographer on the website? (yes). Could it book travel for people outside of the United States to Cuba? (no).

The middleman-reliant, cash-driven solution is most likely a temporary one. The same policy changes that allowed Airbnb to legally operate in Cuba also allow credit card companies like MasterCard and American Express to operate there. Cuba just got its first free public Wi-Fi hotspot last month. And a service called Nauta launched last year (with some hiccups) that Cubans can use to respond to emails using phones. Longer term, it would be surprising if in the midst of all these changes, Airbnb did not figure out a solution that cut out its middlemen.

In the meantime, the system allows Airbnb to get a foot in the door in what is poised to become a much more popular tourist destination. The country presents a rare opportunity for the 7-year-old startup to set up before U.S. hotel chains have the chance. Straight-up tourism to Cuba is still not allowed (some of the categories of travel it has opened include journalistic or religious activities, visits to close relatives, and academic study), but that may not always be the case. As several full-page advertisements in newspapers about the new Cuba offerings have made clear, Airbnb is staking a claim in that business early on.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(196)