Robots Are Going To Kill Jobs Because They Already Have

Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin says automation isn’t something he loses sleep over: “It’s not even on our radar screen . . . [it’s] 50 to 100 more years” away, as he said at an event organized by Axios. “I’m not worried at all,” he added. “In fact I’m optimistic.”

Mnuchin’s statements contrast with warnings issued by the last administration, which produced reports looking at the economic impact of automation. It said, for instance, that 1.3 million to 1.7 million truck drivers could lose their jobs as a result of self-driving technology. “We are going to have to have a societal conversation about how we manage [robots and automation],” Obama told Wired.

New research shows Obama perhaps had a better sense of reality than Mnuchin does. Looking at the effect of industrial robots across the U.S., it shows how automation is already leading to job losses and wage decreases at a significant scale and that new jobs are not being created at a fast enough rate to take their place. The paper adds weight to those who say we should be addressing the social impact of artificially intelligent machines, perhaps with radical policies like a universal basic income.

You can put the divide between Obama and Mnuchin down to politics (surprise!). The Trump team has blamed trade policies, overregulation, and immigrants for job losses in the heartland, not automation. But the contrast is also reflected in the views of economists. Some say robots will replace humans in the workplace, causing widespread job losses. Others say these fears are overblown: that automation, like previous technological upheavals before it, will displace some workers, but create new ones to compensate.

The trouble with the debate so far is this: It’s impossible to know because it’s based on future projections and less-than-scientific methods. The we-should-worry camp points to research showing automation’s potential–for example, one highly cited Oxford University study showing that 47% of U.S. workers are at risk over the next 20 years. It hardens its case by pointing to novel technology appearing every day, including delivery and security bots. Meanwhile, the we-shouldn’t-worry camp points to analogies like washing machines in 20th-century England and how many highly industrialized societies, including Germany’s, are at or near full employment (that is, everyone who wants a job has one).

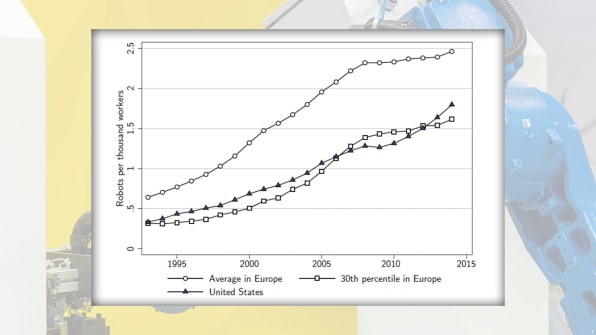

The value of the research is that it’s based on empirical results–what’s actually happened on the ground. It looks at the impact of automated industrial machinery in the U.S. between 1990 and 2007. And what’s more, the work by Daron Acemoglu, an economist at MIT, and Pascual Restrepo, from Boston University and Yale, discounts other factors, including how U.S. manufacturers off-shored thousands of workers to China and Mexico in the same period.

Acemoglu and Restrepo are unambiguous about how robots in automotive and other factories reduced employment. They say that each new robot has reduced the need for up to 6.2 workers in certain isolated areas, and that due to the adoption of automation, wages fell by between 0.25% and 0.5% (about $200 for an average annual paycheck).

“Because there are relatively few robots in the U.S. economy, the number of jobs lost due to robots has been limited so far (ranging between 360,000 and 670,000 jobs . . .),” the authors write. “However, if the spread of robots proceeds as expected by experts . . . the future aggregate implications of the spread of robots could be much more sizable.”

The paper found that automation affects women and men equally but that, according to the economists’ model, men are almost twice as likely not to return to employment. That could be because women are more likely to accept new jobs at lower wages, Acemoglu has said.

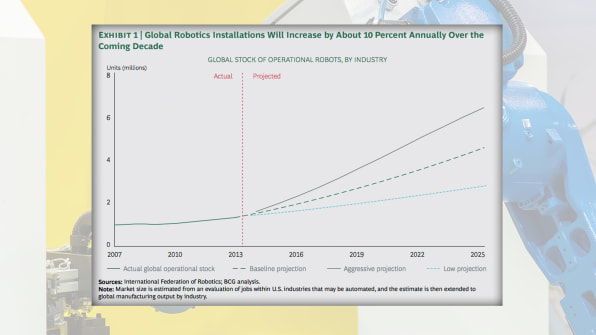

The International Federation of Robotics says there are about 1.5 million industrial robots in the world today. The Boston Consulting Group forecasts that to grow to 4 million to 6 million by 2025. If the increase in robots corresponds with Acemoglu and Restrepo’s ratio of job losses, the job losses could indeed be sizable, running to the many millions. And that’s before we talk about automated machines outside industrial settings, including in offices, retail stores, and fast-food eateries.

We can continue to debate the impact of automation on employment, but probably it should be on our radar screens and we should be debating ways to deal it, including greater investments in training, supporting contingent forms of work, and even a basic income. Robots are going to break apart the workplace long before 100 years are up.

(53)