The Failed Race To Build The Hyperloop Of The 1870s

In 1885, the New York Times published an obituary for an inventor named Rufus Henry Gilbert, who had died alone and broke at the age of 55, “due to exhaustion, brought about by chronic inflammation of the bowels.” He was “penniless and heartbroken,” another source writes.

Just a few years before, Gilbert had received a charter to construct an air-powered subway in New York City—and he wasn’t alone. In the years leading up to the 20th century, a rash of inventors and entrepreneurs were trying to solve the problem of mass urban transit, and compressed air was just as likely a method as, say, steam or electricity.

Who were these long-forgotten inventors? What happened to make their dreams historical footnotes? And as we watch the first hyperloop test track in operation this week, can today’s transit dreamers learn anything from their failures?

The Great Mechanical Problem Of The Present Age

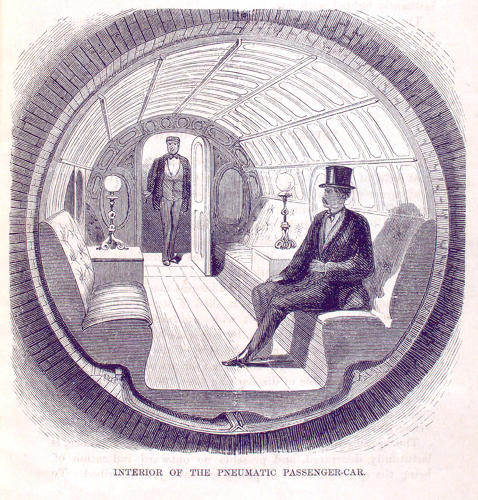

First there was Albert Beach, the son of a rich newspaper owner who, in 1865, patented a design for an air-powered subway car pushed along a track by large fans at either end of the tube. “A tube, a car, a revolving fan!” he wrote in a dispatch on the topic. “Little more is required,” as opposed to “the ponderous locomotive.”

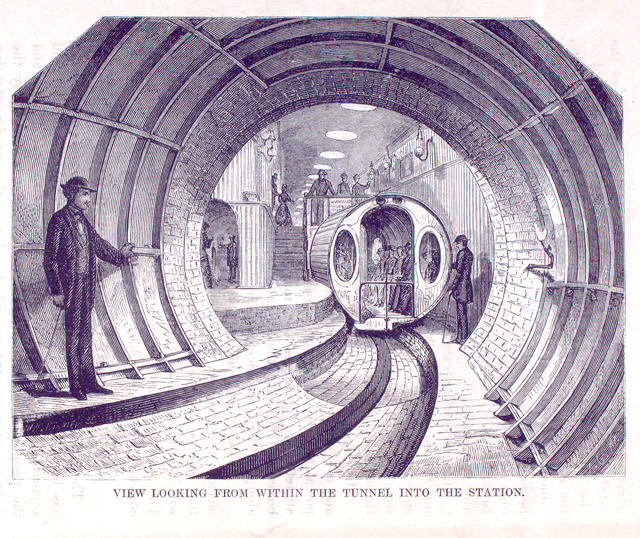

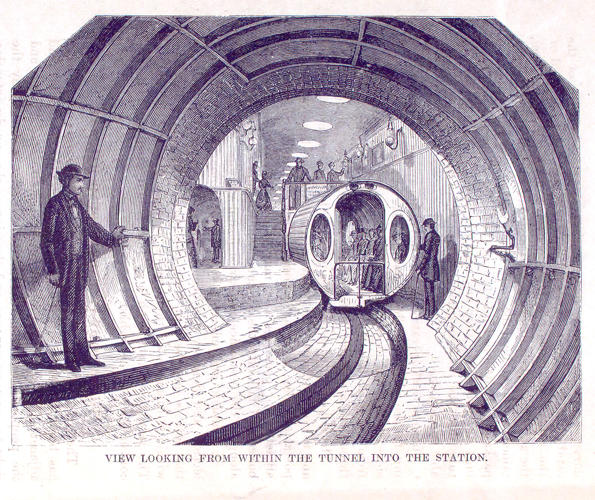

Rather than wait for permission to build a test track, Beach concocted an incredible scheme to build it in secret below the streets of Lower Manhattan. After getting permission to build a system for pneumatically moving mail, he actually got to work on digging a full, subway-sized tunnel, as Joseph Brennan recounts in his history. And two years later, in 1870, unveiled the lavish demonstration tunnel to the media and public.

Beach could have been writing today when he declared, “the accomplishment of the longest distance in the shortest time is the great mechanical problem of the present age . . . whether relating to the transit of words, materials, or individuals.”

Then there was Rufus Henry Gilbert, a former surgeon who dreamed of creating a truly egalitarian form of mass transit. It would be clean. It would be cheap. It would improve life for citizens by letting them move quickly around the city, without billowing pollution or leaving horse droppings in its wake. “Gilbert had become convinced that rapid transit was the cure for the problems of the urban poor,” writes historian Roger P. Roess. “Good transit, he reasoned, would allow the urban poor to move out to more desirable, more sparsely populated areas, where their health would substantially improve.”

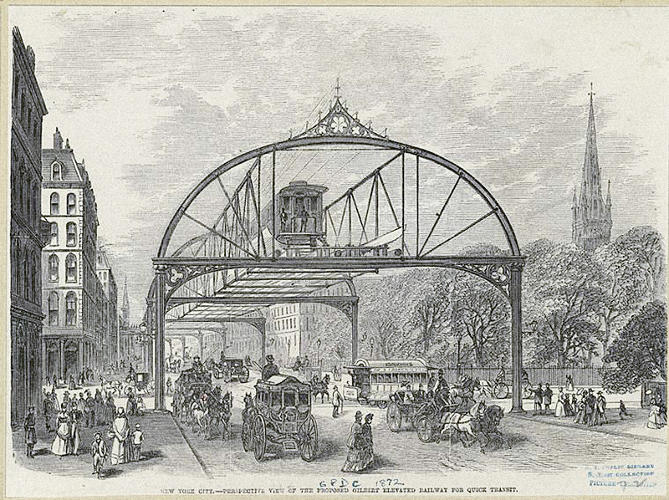

As Beach’s secretive ploy to prove the feasibility of pneumatic transit moved forward below the streets, Gilbert was hard at work above it, building a company to construct his own elevated pneumatic train above. It received a charter in 1872 to build the train along Sixth Avenue, a spindly steel structure that would democratize transit in New York City.

The language both inventors used feels totally contemporary—in fact, you can compare them side-by-side. Pneumatic transit would be faster—”a speed of 100 miles an hour or more may be safely realized, or four times the speed of many of our best railroads,” wrote Beach. So will the hyperloop, as Rob Lloyd, CEO of Hyperloop One, claimed (May 17, 2016) in the Wall Street Journal: “We will reduce the cost of the hyperloop until it is two-thirds the cost of a high-speed rail system at three times the speed.” Pneumatic trains would be cleaner and quieter: “No screeching whistles or jangling bells . . . no running down of the helpless, no mangling of passengers, no burnings from sparks,” Beach continued. Likewise, Lloyd (May 17, 2016) described the hyperloop as “a more immediate, safe, efficient, and sustainable high-speed backbone for the movement of people and things.”

And most importantly, both inventors emphasize—a century apart—that their plans are real: “The pneumatic dispatch is not a chimera, nor merely an untried, undeveloped novelty,” Beach wrote in his treatise. “The hyperloop is real. It’s happening now,” Lloyd said (May 17, 2016), according to the WSJ.

So, what happened to Beach and Gilbert? It wasn’t a problem with technology that defeated their plans—it was politics and economics. Beach’s sneaky demonstration subway was struck down by Boss Tweed, the notoriously corrupt political ruler of New York City. Even when he gained permission to extend the line, he failed: The Panic of 1873 sent the project into a tailspin from which it never recovered. “Overnight, interested investors withdrew support and the dream of a New York subway was again deferred,” explains a PBS documentary on the project. “It would be another 25 years before talk of a subway was taken seriously.”

Gilbert’s elevated dream unfolded in an even more heartbreaking way. The Panic struck just after construction had begun—and so he took on investors. “They swindled him out of his stock in his own company after pushing him to abandon pneumatic power for steam power,” Roess writes, in a scenario that sounds eerily similar to what you might see on Silicon Valley. “He was voted off the board the day after the line opened. He spent seven years and most of his money in court trying to regain the rights to the railroad he had created. He failed, and died at the age of 53, a virtual pauper.”

It’s Not A Race, It’s An Odyssey

(May 17, 2016), one of several companies trying to turn Elon Musk’s hyperloop into a reality gathered the media for an exciting demonstration of the technology. As the first hyperloop test capsule rocketed across the desert landscape, it was hard not to think of Beach’s own widely publicized unveiling of his pneumatic train system below Manhattan. Both moments were full of optimism about how transit could not just make moving around the world easier, but make it cleaner, faster, and less expensive.

But the biggest hurdle for these long-gone inventors wasn’t building a working prototype—it was the market, and competition from other forms of transit. As the competition around the hyperloop heats up, it’s worth pointing out that regardless of who does it first—and what type of magnets they use—the real challenge may be implementing a system that makes financial and political sense. As others, including Paleofuture’s Matt Novak, have pointed out, land rights and bureaucracy will pose another big challenge, perhaps even larger than the technology itself.

So far, we only know the rough outlines of how either company plans to clear those hurdles—but both seem to be turning to Europe to start. Hyperloop One’s main competitor, the crowdfunded company Hyperloop Transportation Technologies, entered into an agreement this year with the Slovakian government to “explore” building a series of tracks throughout central Europe. It also has plans to build a working hyperloop track in a new development in central California, called Quay Valley, to serve as a proof of concept.

Hyperloop One, meanwhile, is casting a wide net: (May 17, 2016) it announced partnerships with Bjarke Ingels, FS Links, and other companies to explore how the technology could be applied as a transit network throughout Scandinavia, while other partners will assess how it could be used to transport goods at ports throughout Southern California and in the U.K. “With hyperloop we are not only designing a futuristic station or a very fast train—we are dealing with an entirely novel technology with the potential to completely transform how our existing cities will grow and evolve, and how new cities will be conceived and constructed,” Ingels said in a statement. That sentiment could just as easily have been uttered by a pneumatic transit advocate, arguing that clean and cheap mass transit was the key to the modern city.

(May 17, 2016) afternoon, we saw the first real test of an emergent technology. It’ll be the first of many firsts and unveilings, as companies clamor to attract funding and attention. But the bigger challenge—of funding and planning a working system that makes good financial and urban sense—won’t just take years, it’ll take decades. With any luck, though, it won’t end in financial ruin or heartbreak.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(57)