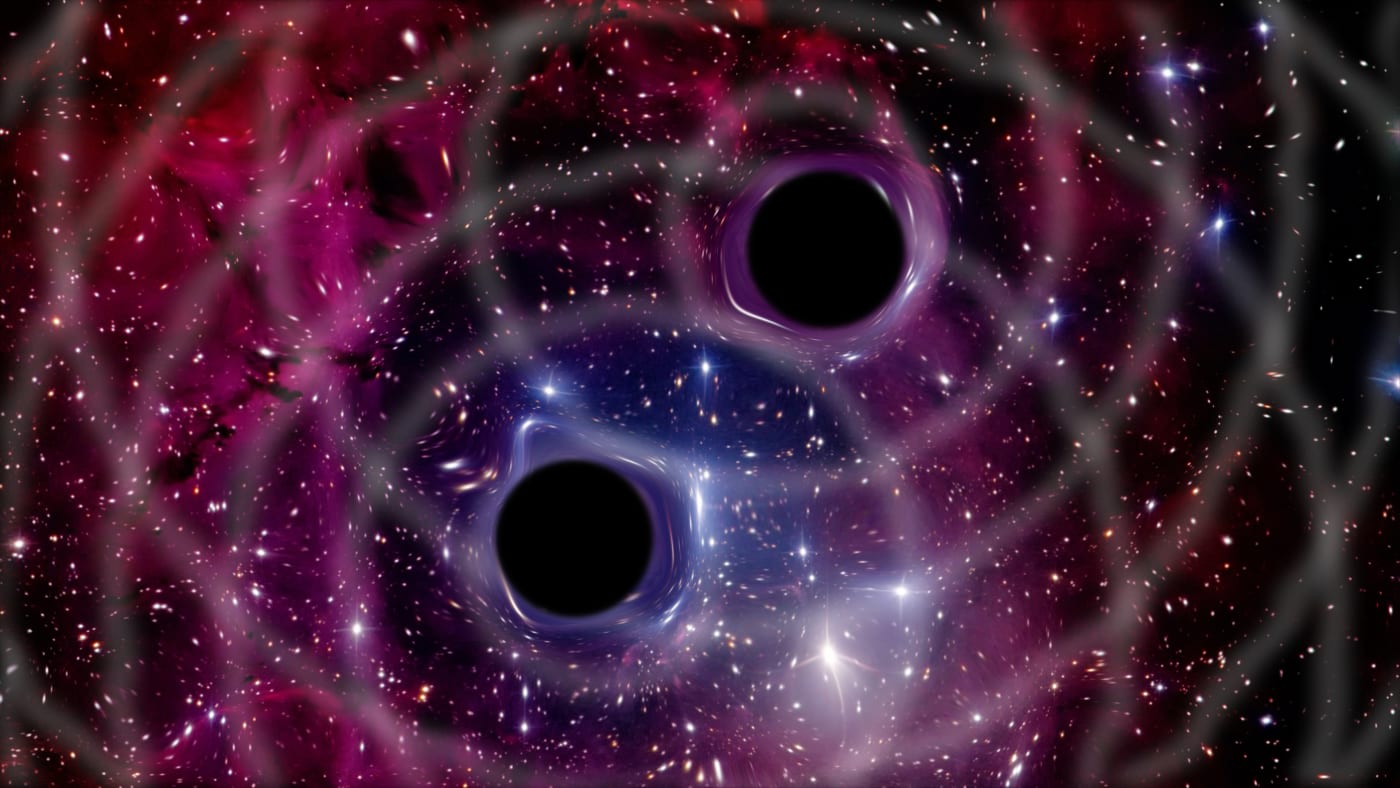

If you were worried that the first confirmed detection of gravitational waves was just a one-off result… don’t be. Researchers analyzing LIGO data have verified a second instance (recorded in December 2015) where two black holes merged and produced the hard-to-spot behavior. The circumstances are decidedly different this time around, though. Ars Technica observes that the black holes were much smaller than those in the first instance, and spent more time on their collision course. While that offered more data to collect, the reduced intensity also introduced more errors — it was harder to determine the masses of these holes.

This kind of cosmic behavior is likely more prevalent than what you’ve seen here. Just don’t expect to hear more about it any time soon. This is the only other event from LIGO’s first run to pass muster, so you’ll have to wait for subsequent tests to hear about more discoveries. Nonetheless, this is enough to show that gravitational waves can emerge in a wide range of conditions.

(33)