The Founder of TED Shares What It Takes To Build The World’s Most Popular Conference

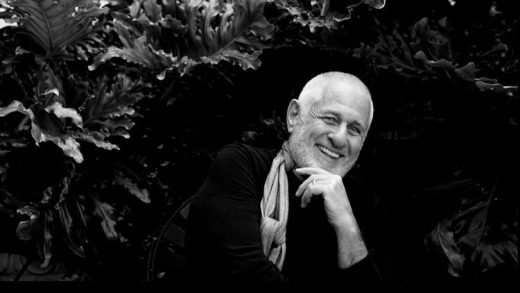

I’ve had two phone conversations with Richard Saul Wurman, the 81 year-old founder of the massively popular TED conference, and both have left me feeling woefully under-accomplished as an individual. If Dos Equis is ever looking for a new “Most Interesting Man in the World” they need look no further than Wurman.

By his mid-20s Wurman had accomplished more than most men twice his age. In 1958 when he was just 23, he took part in expeditions exploring and mapping the ruins and rainforests of Tikal, Guatemala. A year later he earned both his bachelors and masters degrees in architecture from the University of Pennsylvania, where he was awarded the Arthur Spayed Brooks Gold Medal. The next year he was off to London where he worked under the renowned architect Louis I. Kahn and helped design the largest barge to travel up the Thames River for Jack Heinz, the owner of the H. J. Heinz company. That barge hosted the orchestral music of the Wind Symphony Orchestra.

In his 30s Wurman was teaching at Cambridge and by his 40s he had begun writing and publishing the first of 90 books on topics ranging from architecture to travel to the nature of understanding. All that doesn’t even include the numerous honorary doctorates and awards he’s won over the years, including the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Smithsonian.

But perhaps his most defining accomplishment, or at least the one he will be remembered most for, happened in 1984 when Wurman was just 49.

“1984 was a wonderful year. There was the first Macintosh, USA Today had just come out, Benoit Mandelbrot announced about a year before (and he was the first in the public eye about) fractal geometry,” says Wurman. “The first CD came out. It was jointly invented by Sony and Phillips, and nobody had a CD player, and that exploded in the world. That was just 1984.”

1984 was also the year Wurman held the first TED conference. It was born from his love of conversation and seeking out and identifying new patterns in information—patterns others have missed.

“I observed in ’84 that there was a convergence going on out there that the people who were within it didn’t understand. They were in it and couldn’t see it. That was [between] the technology business, the entertainment industry, and the design professions,” Wurman says, explaining where the TED acronym came from. “They just didn’t see that they were one group…they didn’t realize they were growing together.”

Since then TED has become the most well-known and talked about conference on the planet, expanding to other disciplines, and becoming a status symbol and badge of achievement for experts who’ve given talks there. But not everything that TED has become pleases Wurman. He sold the rights to the main conference in 2002 and since then some say it’s become elitist and pretentious. Still Wurman himself hasn’t lost faith in the power of gatherings, as he prefers to call them, to spread ideas. Indeed, he’s gone on to create other conferences including WWW.

If you’re thinking of starting a conference, Wurman says there’s no right way to do it, but here’s what worked for him.

1. Only Do It Because You “Have” To

When I ask Wurman what the single most important thing is when pulling off a good conference he gave me a most unexpected analogy. “In the middle of the night, almost every night, I get up because I have to pee. I go wander around the bedroom to find the bathroom, I pee, and I go back to sleep. I get up because I have to do something,” he says. “You only do a conference because you have to.”

Wurman says that if he started building a conference because he wanted to make money from it or because someone asked him to do it, he probably couldn’t have pulled TED off—or had any kind of desire to do so. TED was born from an overwhelming need to fulfill his personal curiosity about the convergence of disciplines he noticed in 1984. Because of that, he was able to give it his all—with an attention to detail only those who are truly passionate about their idea could provide.

“I picked out every bit of food that was served at every meal. I designed the badges, and they were unique badges. I chose the furniture and had it made by Steelcase for me. I called the people who I wanted to maybe sponsor a meal. I designed the stage, I picked all the speakers,” Wurman says of the first TED conference. “Most of all, I worked as much on doing the ordering of people, and what order they came over four or five days. Who follows who, and who was before who. Like an editor would for a film, I spent a lot of time on editing what I thought was this arc. A lot of time—an inordinate amount of time. I chose all the music. It was my fucking party. If it didn’t work, it was me that screwed up.”

When I mention that his attention to detail reminded me of Steve Jobs’s legendary, almost obsessive, oversight of Apple’s products, Wurman says that unknown to most people the Apple cofounder actually attended the first TED in 1984. “He came to the first one, but he wouldn’t come on stage,” Wurman says. “He brought the first three Macs that anybody could ever see. It was right after the Super Bowl, and that one ad. People could play with the first three Macs for the first time ever, in 1984.”

You’re not going to get that type of interest from people in your conference if it’s not obvious you’re truly passionate about it.

“I do the conference I want to go to,” says Wurman. “In our society, that’s thought of as being non-PC, a pompous arrogant asshole. But it isn’t. It’s actually just a thoughtful way of doing things.”

2. Get Rid Of The Normal

The next thing Wurman did when founding TED was to go contrary to the norms of conferences. Back in the 80s—and even today—Wurman says the norm is that most conferences have a very similar format.

“The sponsors and the speakers were cordoned off in the first two rows, so it was them and us. There was always a separation of castes there. Everybody wore a coat and tie. There was a lectern, and you stood, man or woman, behind the lectern because it protected your groin, and therefore, you felt less vulnerable,” says Wurman. “You read a speech, and you gave PowerPoint slides later on. You were given an introduction, and the more important you were, the longer the introduction. That was the model, and it still is the model for most gatherings. It’s utter boredom.”

And when you are bored, Wurman says, you do not learn. “My definition of learning is remembering what you’re interested in. You cannot fault that phrase. It’s the fundamental definition of learning.” So Wurman got rid of the lectern so speakers didn’t have anywhere to put notes down. That forced them to think off the cuff and have a conversation with the audience organically instead of reading a prepared speech. It also kept the talks shorter, which kept people more interested. And if Wurman did sense that the talk was going on too long, he did something about it.

“I was on the stage 100% of the time. I sat over on the side,” Wurman says. “When a speech was boring, or it went too long, I would get up and very quietly walk over and stand behind the person. They felt me there and they realized they had to come to an end.”

Wurman’s setup and tactics could make his speakers feel vulnerable, but that was the point. Vulnerability causes us to lets our guards down. With our defenses lowered we’re more honest and believable. “What do we you want from a speaker? We want to believe them,” he says.

Eschewing the norms and formats of the traditional conferences didn’t only get the best talks about of the speakers, it kept the audiences clamoring for more, Wurman says. “The doors did not open until about three minutes before each session. People lined up around the lobby. Everybody wanted to rush in, and unlike any other gathering there was a gestalt there that had people running and wanting to sit in the front rows. Most every talk, people go to the back. They want to be able to walk out and not disturb people. [With the format of my speaker’s talks] people knew they weren’t going to do that, so it was jammed.”

3. Please Yourself When Choosing Speakers

Unlike most conference organizers, who agonize over which speakers their attendees might want to hear from, Wurman, quite frankly, wasn’t worried about pleasing his audience because to do so, he says, you would need to know what another human being is thinking—and that, he notes, is impossible.

“You never know what another human being is thinking. That is an arrogance beyond arrogance,” he says. “Once you realize that you don’t know what somebody else is thinking, why bother trying to please them? Why not just do good work and please yourself?”

And that’s how he chooses his speakers for his audience: They’re solely a person Wurman wants to hear from.

“Once or twice you do that, and you realize that the audience generally likes it; once you try not to have an effect on people—but you historically know that you have had an effect—you just let go of that and do good work,” he says, and has the proof to back up that his concept works. Within a few years his conferences began to sell out—a year in advance. “I would give a conference, and then on the last day, I said ‘You can now register [for the next one],’ and it sold out. I sold 1,000 seats, and had their money for a year. They didn’t know who the speakers were going to be.”

4. It Doesn’t Have To Be Big To Have A Big Impact

When most think of conferences they think of the massive events like TED or Apple’s WWDC or Google’s I/O that draw thousands of attendees. But despite Wurman’s various conferences drawing thousands each year over the decades, he doesn’t believe that a conference has to be massive to be successful, or even to help change the world.

Case in point: Last April, Wurman held a small conference he dubbed “The Event.” It consisted of him, cellist Yo-Yo Ma, architect Frank Gehry, RadicalMedia owner Jon Kamen, and urban designer and theorist Moshe Safdie. The Event wasn’t publicized or announced and only had 20 attendees, most of whom were people Wurman had met on the street that day. The five men sat around in a circle in front of the small audience and for 90 minutes shared some wine and sugared pecans and had a conversation about the notions of envy, admiration, and terror. Though the gathering was filmed by five cameras, the footage has never been released.

“There’s a conference in its smallest form,” Wurman says. “A semi-formalized dinner party, without dinner. Just a little chat among friends that came in, because they could, from around the world.”

“The goal wasn’t a sponsorship. There was no money involved. The people went there themselves, then they left. There was nothing written about it, it wasn’t reviewed, and there’s never been a story about it.”

But a small conference could still have a far-reaching effect, Wurman believes. After all, he points out, the thousand people that attended his first TED conferences, though larger than 25 people at The Event, were still relatively insignificant in the larger scheme of things. “One thousand people are just an accountant error. It doesn’t mean anything. The thousand people that came to TED were statistically meaningless against the 300 million people in America.”

Yet look what spawned from that original gathering of only a thousand people in a world of 7 billion: Wurman’s TED conference has gone on for over 30 years and spread ideas to millions of viewers who, combined, have watched TED talks over a billion times. And who knows how, in turn, those viewers will act on those ideas to the benefit of the world? Who knows what one of the 20 people who attended the Event might do based on the ideas discussed at the dinner party without dinner? Which of the ideas discussed might they share with others that could ultimately result in some new product or solution or theory?

“You don’t have to sell a million books to have an effect, or to make something clear, or to work out clarity in life,” Wurman says. “Small groups, if they’re the right small groups, and they’re filtered down naturally to people who tell other people, that’s quite enough. Viral communications is really quite interesting.”

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(30)