The way to a man’s heart is actually through WiFi

They say you can’t hide what’s in your heart, but the saying is doubly true for an Ohio man whose pacemaker data has been used to indict him on felony charges of aggravated arson and insurance fraud.

Police investigating a fire at Ross Compton’s house said he gave statements that were “inconsistent” with the evidence. Compton didn’t reckon on authorities obtaining a search warrant for all electronic data stored in his cardiac pacing device, and now he’s going up the river for burning his own house down.

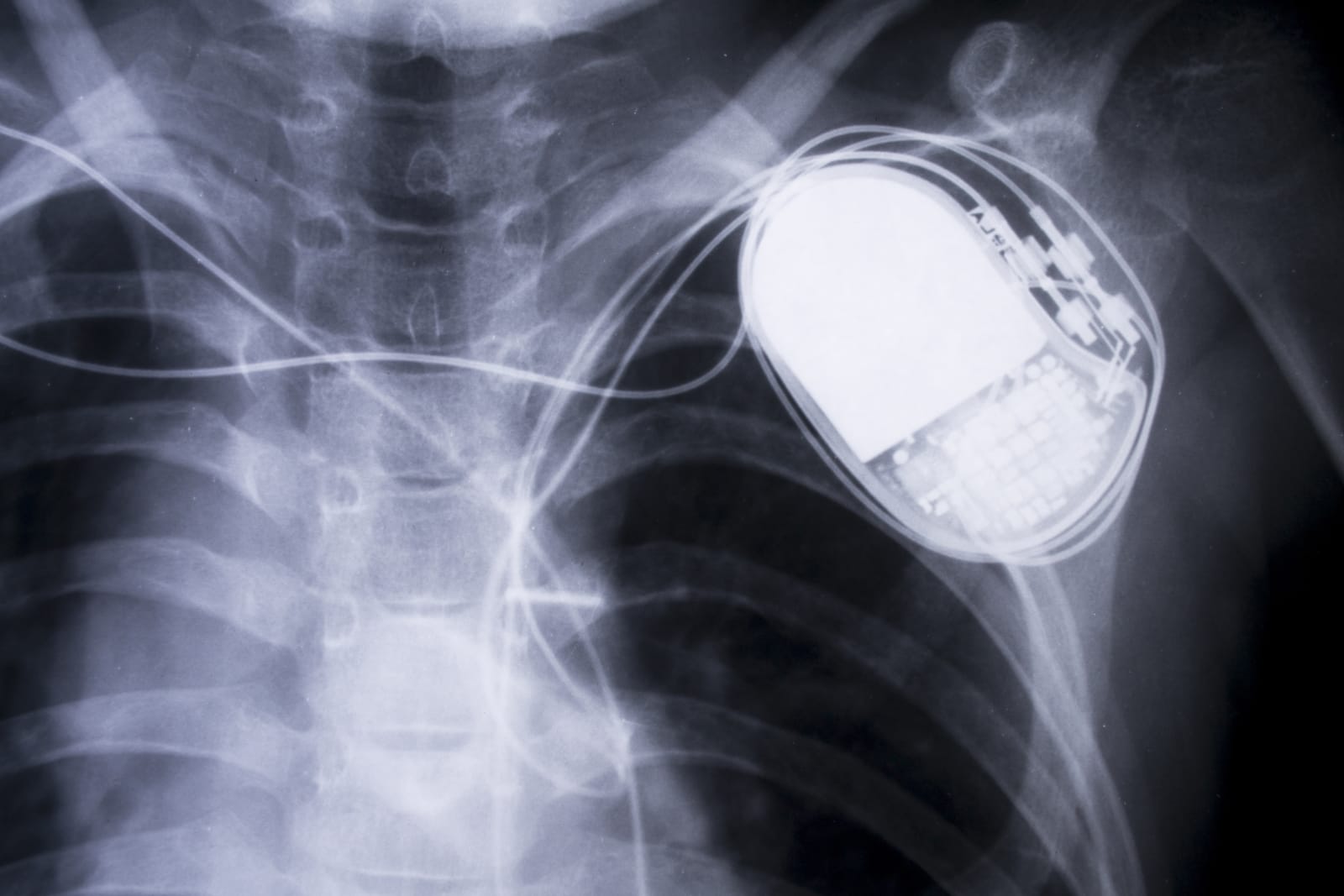

According to court documents obtained by press, the data from Compton’s pacemaker, examined by investigators, included his heart rate, pacer demand and cardiac rhythms prior to, during and after the September 2016 fire.

A cardiologist who reviewed that data concluded it was “improbable Mr. Compton would have been able to collect, pack and remove the number of items from the house, exit his bedroom window and carry numerous large and heavy items to the front of his residence during the short period of time he has indicated, due to his medical conditions.”

Meaning, they looked at the time window of the fire and his tale of escape along with his heart rate, and decided that his story didn’t add up. That’s as far as we know, anyway. If we learned anything from the St. Jude stock debacle, it’s that implantable medical devices and their home monitors probably carry (and probably leak) data that could pin a person down more than a few heated beats at the wrong time. Like transmitting activity records, heart rate logs, and sensitive patient information.

Last September short-selling firm Muddy Waters and its business partner, security company MedSec Holdings, released a scathing and now-contested company report saying that pacemakers and heart devices made by St. Jude Medical had critical security flaws.

Effectively, it’s only thanks to hackers that the general public has learned that pacemakers have built-in functionality for wireless communication. This means a lot can be learned about our activities by what networks they connect to, and when. The interface is largely for remote monitoring purposes, where a device connects to a server at the vendor to transmit device logs and patient information.

This is the medical Internet of Things. And now it’s a tool for authorities and insurance investigators.

His heart wasn’t in it

Mr. Compton had originally told officers that when he realized there was a fire he packed a suitcase and some bags, then broke his bedroom window and threw everything out of the house before packing up his car. He claimed to have escaped with his belongings and his life. A neighbor told press that when he saw Compton carrying a computer tower, Mr. Compton asked him for help putting it into his car.

According to a search warrant obtained by media, fire investigators said there were multiple points of origin of the fire from the outside of the residence. Compton’s statements to 911 also conflicted with what he told police, and he was arrested just two days after the fire. It’s likely he never thought that in a million years his pacemaker would rat him out. And why would he?

It was just a matter of time until we started to find out if medical device data is protected by the Fifth Amendment’s safeguards for self-incrimination. Those following the fingerprint-password debates know that a Virginia Circuit Court judge ruled in October 2014 that giving biometric data is not the same as divulging knowledge.

Compton’s heart condition was well known by investigators from the get-go: He was briefly hospitalized after the fire with a related medical issue. So it’s not too much of a leap for someone to wonder if there was a way to track his movements after a fashion with the constant record being created by his pacemaker.

Sounds like a pretty damning avenue for investigation, using pacemakers to catch criminals with an ironclad dataset for prosecution. Except as one hacker found out when she had to be kitted out with a heart device, these internal trackers don’t always give off the correct data.

Infosec professional Marie Moe got her pacemaker in an emergency procedure to save her life, but it wasn’t long before she realized the pitfalls of these deeply personal IOT devices. Soon, she was debugging her own heart, which sounds almost romantic, except it’s not. Because she was younger than the typical pacemaker user, hers required a lot of adjusting.

Moe experienced months of trial-and-error tweaking from doctors who couldn’t quite get her heart’s tuning right. She said: “This was complicated by a software bug in the programming device that they used to adjust the settings of the pacemaker. The bug caused the actual settings of my device to differ from the those displayed on the screen at the hospital that the pacemaker technician was seeing.”

The impact of this was significant, as Moe explained. “The consequence of this greatly affected my well being. If I tried to run after the bus or climb up stairs I would suddenly get out of breath. The pacemaker was detecting my pulse to be outside the upper heart rate limit, which was erroneously configured to 160 beats per minute. When I reached this heart rate, the pacemaker would suddenly cut my pulse in half to 80 beats per minute due to a safety mechanism.”

Not only could the device be performing improperly and sending incorrect information “home” to its servers, Moe discovered that she wasn’t allowed to access her own data. Along with other pacemaker users, she started fighting for her rights to get access to the data that their devices are collecting.

It feels very ominous and Big Brother-y, that authorities can just grab data from devices inside your body without your consent.

Of course, it’s not just implanted medical devices that monitor people’s heart rates, transmit device logs and bodily information — and snitch out anyone with something to hide. Fitness trackers like Fitbit, Garmin, and Jawbone are increasingly being used as admissible evidence in court cases. The difference here is, that you can’t just leave a pacemaker on the bedside table when you want.

If we were all living in a dystopian fiction novel, Mr. Compton’s crime getting foiled by Big Brother’s access to the actual inner workings of his heart would be somewhat chilling in its implications.

Good thing our current climate doesn’t feel dystopian or unreal at all right now.

(37)