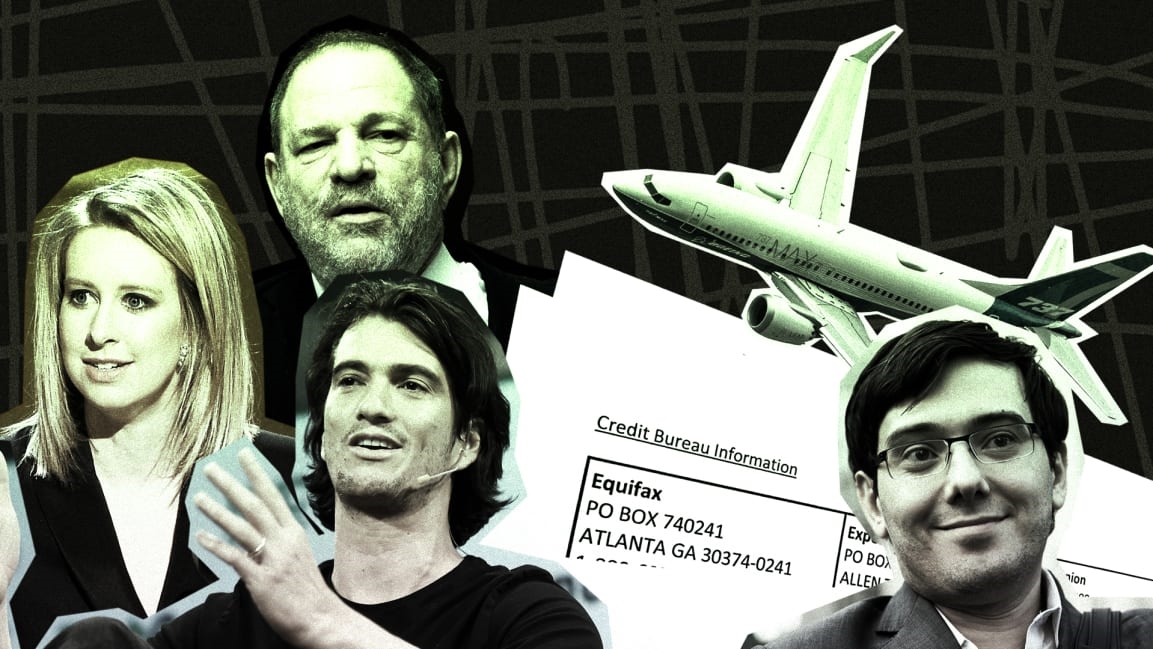

These are the worst scandals of the past decade

At the end of the year, Fast Company usually rounds up of the best and worst leadership moments of the year. But given that 2019 also marks the end of a rather eventful decade, the stakes felt higher.

We asked ourselves: Over the past 10 years, what were the worst scandals—the greatest leadership failures, the big-time grifts, or the most toxic workplaces—of the decade? In short, which events really transformed the way we think about business and leadership?

Compiling this list proved to be a daunting task. In order to make the cut, these scandals—many of which gripped the public’s attention when they broke—had to be truly remarkable. The “winners,” which appear below in no particular order, showcase the actions of the worst grifters, villains, and scumbags of the 2010s.

Let us know what else should have made the cut, and here’s hoping there are fewer contenders for this list next decade.

Sexual misconduct allegations

The decade has been defined by the #MeToo movement, which was sparked by the New York Times investigation into Harvey Weinstein. Powerful men have long faced these sort of allegations: Roger Ailes, for example, had been forced to step down from Fox News the year prior, following harassment allegations from the likes of Gretchen Carlson and Megyn Kelly. But the Weinstein story opened the floodgates—not just for his other alleged victims, but for countless others who had previously felt like they couldn’t come forward.

Amongst the other prominent men accused after Weinstein was the CEO of CBS, Les Moonves, who exited the network after 12 women levied sexual harassment and assault allegations against him—and many more claimed the company had looked the other way or settled with accusers to cover up sexual misconduct across the network. Still, Moonves maintains his innocence, and Weinstein, who recently reached a $25 million settlement with his accusers, has denied allegations of nonconsensual sex and, in recent weeks, has branded himself a “forgotten man.”

Big pharma

The founder and former CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals—perhaps better known as “pharma bro” Martin Shkreli—saw his fortunes turn in late 2015, soon after he infamously raised the price of a drug his company acquired by more than 5,000% virtually overnight. Shkreli was eventually found guilty of multiple counts of fraud (not for the price inflation but because of business dealings in his previous life as a hedge fund manager). Still, he wasn’t alone in driving up drug prices: Before Shkreli, there was former Valeant Pharmaceuticals CEO Michael Pearson, who used exorbitant price increases to keep shareholders happy—and after Shkreli, Mylan CEO Heather Bresch, who came under fire for jacking up the price of the EpiPen in 2016.

But the real Big Bad of Pharma in the 2010s may well be members of the Sackler Family, whose company, Purdue Pharma, was responsible for aggressively marketing OxyContin, the drug that has been accused of fueling the opioid crisis. The company recently filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in an attempt to protect itself against thousands of lawsuits.

Transportation scandals

This month, Boeing finally pulled the plug on production for the 737 Max. The decision came nine months after Boeing grounded the jet in response to two disastrous crashes that killed 346 people. This has been called the worst crisis in Boeing’s 103-year history, one that is already affecting suppliers and is projected to have ripple effects on the economy, given its standing as the biggest exporter in the U.S. The company fired CEO Dennis A. Muilenburg on Monday.

Takata, too, failed to protect customers when it used a volatile compound to power the inflator in its airbags, a decision that led to the recall of tens of millions of airbags—the largest automotive recall in history—and has since left the company bankrupt. And as of this month, Takata is the target of yet another recall of a similar scale.

Another automotive company is still reeling from the effects of its biggest crisis: In 2015, Volkswagen was accused of using illegal defeat devices to circumvent diesel emissions standards. The company initially tried to pin the fraud on a group of engineers, but former CEO Martin Winterkorn has since been charged in the U.S. and Germany. (Volkswagen declined to comment on the charges, according to the Times, as did Winterkorn’s lawyer.) Over the past four years, the company has doled out $33 billion in fines and settlements.

Data breaches

As more and more people have handed their data to tech companies, data breaches and hacks have grown both larger and more frequent. Hackers who targeted Equifax in 2017 compromised the personal information of 147 million Americans—more than half the population—gaining access to Social Security numbers, credit card details, and more. Facebook was the target of an especially high-profile leak—when Cambridge Analytica harvested the data of tens of millions of users—but a string of breaches in recent years has exposed the data of hundreds of millions of users.

The list goes on: In 2013, hackers took aim at Target and exposed the credit and debit card numbers of 40 million customer accounts, while Yahoo was hit by a breach that affected all three billion of its users; last year, Marriott revealed that hackers had stolen the personal data of up to 500 million guests.

Toxic work culture

At the start of the decade, companies like Google seemed to have cracked work culture—or at least a version of it that promised endless perks. In some cases, an emphasis on employee bonuses may have papered over deeper culture issues. Last year, a Times report revealed Google had paid Android creator Andy Rubin $90 million when he left the company after allegations of sexual misconduct. Rubin has denied the accusations and told the Times they were part of a “smear campaign” by his ex-wife. The news sparked the Google Walkout, which drew 20,000 employees across the world and subsequent employee activism.

More recently, we discovered that things at WeWork were not what they seemed. The company was riddled with financial troubles and leadership issues; cofounder and former CEO Adam Neumann reportedly called all the shots and had created a culture where employees could not challenge him. He was also accused of discrimination and harassment in multiple complaints. WeWork’s upcoming IPO was shelved, and Neumann stepped down in September. (Neumann has not commented on these allegations, but WeWork has said it will defend itself against pregnancy and gender discrimination complaints.)

Of course, before WeWork, there was Uber. In early 2017, Susan Fowler penned a blog post detailing her experience of sexual harassment at Uber, which was followed by similar allegations from other Uber employees. For years, the company had embraced a growth-at-all-costs mindset, flouting laws and decreasing pay for drivers. Travis Kalanick stepped down as CEO in response to pressure from shareholders.

The frat culture that led Kalanick to set guidelines for having sex with other employees extended to other startups like Zenefits, which memorably had to instruct employees not to have sex in stairwells. At American Apparel, founder and former CEO Dov Charney was dogged by sexual misconduct allegations for years, which included saving photos and videos of sex acts with employees on company computers. (Charney’s lawyer has previously called into question the claims made against him.) Charney was eventually ousted from the company for misusing company funds.

Then there were the companies driven by hustle culture: In 2015, a Times exposé of Amazon‘s corporate culture—an account the company contested in a lengthy Medium post—detailed a cutthroat environment where employees reportedly wept at their desks. One of their key leadership principles, which are guidelines the company holds dear, was “customer obsession,” an idea that was also embraced by Away cofounder and former CEO Steph Korey, who recently stepped down after a report described a culture of long hours and limited time off. And we’d be remiss not to mention Elon Musk, who justified Tesla’s brutal work culture by noting he works even harder than his employees, spending nights at the factory and working 120-hour weeks.

Labor issues

Amazon‘s working conditions for warehouse employees have also come under fire. Most recently, an investigation by Reveal found that Amazon’s emphasis on speed and customer satisfaction had significantly impacted its rate of serious injuries, which, in many warehouses, was more than double the average in the warehousing industry. An Amazon spokesperson told Reveal its injury count is higher because the company is thorough about documenting worker injuries.

Many gig companies have built their businesses on the backs of contract workers, from Uber to Instacart, often making changes to the pay structure with little notice. Protests over Disney reportedly underpaying workers at Disneyland and Disney World eventually led to a wage increase that set minimum pay at $15 an hour. The fashion industry has been complicit in severely underpaying workers and allegedly employing slave labor, from Forever 21 to Zara. Even the European workers employed by luxury brands are subject to alleged worker exploitation. In recent years, fast fashion companies have been taking a closer look at their supply chains, in response to criticism of their labor practices and a disastrous incident at a Bangladesh factory in 2013.

The fall of social media

This decade saw social media’s reach and influence grow exponentially. Instagram appeared on the scene in 2010; two years later, Facebook acquired the platform for $1 billion and became a publicly traded company. Over this decade, YouTube has more than doubled its monthly users (in 2019, that figure crossed two billion), while Facebook’s user base has grown by more than six times. With 2.45 billion monthly users, Facebook remains the most popular social media platform, followed by YouTube and Instagram.

But as Big Tech emerged, something shifted: Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube became breeding grounds for misinformation, hate speech, and harassment. Both Twitter and YouTube have more recently taken steps to mitigate harassment, but for years, they have failed to adequately address the problem, whether that meant allowing white nationalists to remain on Twitter or acting too slowly to remove extremist content.

The very thing Mark Zuckerberg cited as Facebook’s greatest selling point—its ability to connect people—had left it vulnerable to bad actors, and after the 2016 election, we learned that Facebook had enabled Russian meddling in the election, with 150 million Americans exposed to Russian-generated content. And in the lead up to the 2020 election, Facebook has said it won’t fact check ads from politicians. While Google and Twitter have introduced guardrails to help curb misinformation, Facebook has yet to announce any such changes to its political advertising policies.

The big grift

The past few years had plenty of corporate scams, such as Wells Fargo, which has been dealing with the fallout from a scam driven by employees who, feeling pressure to meet sales quotas, opened millions of unauthorized bank and credit card accounts.

But it was the actions of individual grifters that especially captured our attention this decade. Billy McFarland sold Fyre Festival attendees on a pipe dream and defrauded investors. And Elizabeth Holmes has a special place in our collective memory. Few grifters have been so thoroughly convincing, and for so long. In a climate rife with inflated valuations, Theranos has become a cautionary tale for founders, investors, and journalists who were taken in by a young woman in a black turtleneck.

And a special mention

In nearly three years of the Trump administration, we’ve witnessed a series of failures in leadership. There was the travel ban, which kicked off President Trump’s tenure and barred immigration from multiple Muslim-majority countries. Soon after, Trump tried to impede the federal investigation into Russia’s interference in the 2016 election. In 2018, the Trump administration implemented a zero tolerance policy that separated thousands of migrant children from their parents and locked hundreds of them in cages. And earlier this year, the Trump administration officially gave notice that the U.S. would withdraw from the Paris Agreement on climate change.

Some of Trump’s worst moments have come in the face of tragedy. After mass shootings, the president has offered little more than thoughts and prayers; following the Charlottesville rally, he refused to denounce the white supremacists involved, instead arguing there were “very fine people on both sides.” When wildfires swept California, Trump critiqued the state’s response, and after Hurricane Maria killed 3,000 in Puerto Rico, he bragged that the government’s disaster response had been an “unsung success.“

(26)