This graph will show you the carbon footprint of your protein

If you want to reduce your personal carbon footprint, you might trade in a car trip for a ride on public transit, or swing by a second-hand clothing store rather than buy fast fashion. You might also take a closer look at what you eat. Food production accounts for one-quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions, and the meat and dairy industries are a big reason why. But if you aren’t ready or willing to give up meat—which could halve the carbon footprint of your diet in one fell swoop—should you consume “sustainable” animal options, change what kinds of meat you’re eating, or just opt for fewer meat-filled meals?

Hannah Ritchie, an environmental researcher at Our World In Data, an online science publication associated with the University of Oxford, sought to answer that exact question. She found that eating less meat is nearly always a better environmental choice, but the choice of meat and where that meat is sourced from matters. Eating plant-based protein, though, makes the biggest difference—no matter where your beans and tofu come from.

Understanding the environmental impacts of our diet can seem overwhelming. There are a lot of factors at play: land use, organic or nonorganic farming, how far that food is shipped to you, how much plastic it’s packaged in. But it really comes down to one crucial factor: what we eat. “Most of the advice out there (even by organizations such as the UN) of ‘eat local, eat organic, use less plastic’ make only a small difference (sometimes even make things worse),” Ritchie says via email. “We need to make changes that have a large impact, and dietary change is a big one.”

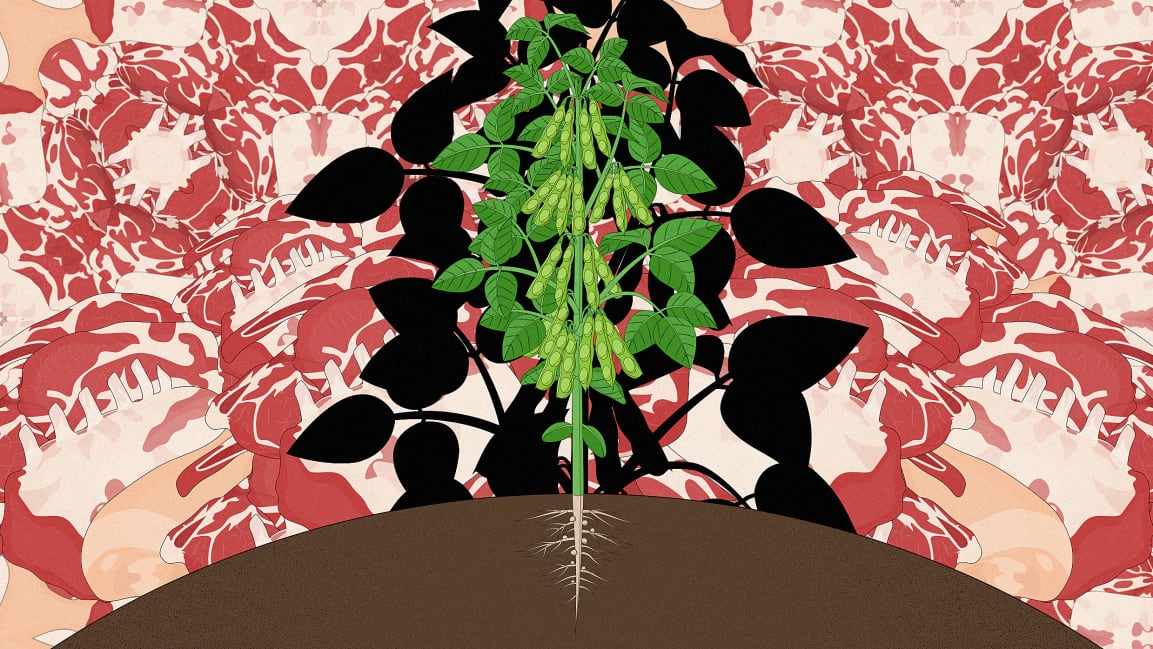

[Image: Our World in Data]

The biggest chunk of our food-related emissions, Ritchie has previously explained on Our World in Data, comes not from transport or packaging but because of land-use change, which is when habitable land has been turned into agricultural land. But a lot of the numbers that are reported about carbon emissions associated with food production, whether of peas or beef, are global averages. That might lead people to think that their burger sourced from a local, low-impact producer is an exception—and better than plastic-wrapped, internationally sourced plant protein—thereby justifying their meat consumption.

But that’s not quite right, Ritchie says. Even the most sustainable meat and dairy producers have a bigger carbon footprint than the worst plant protein manufacturers. “So even your tofu shipped to you across the world and wrapped in plastic will have a lower footprint than meat,” she says.

Ritchie created a graphic that compares the carbon footprint of all types of proteins, and includes the caveat that that carbon footprint can change, depending on how and where it’s produced. The white dot for each protein on the graphic represents the global average. If you’re concerned about how much plant-protein you’d have to eat to match your meat intake, though, and if that would skew the environmental benefits, don’t worry; Ritchie factored that in, as well.

“Rather than comparing products in terms of kilograms or calories, here we do a direction comparison of per 100 grams of protein,” she says. “And we did not include sources of ‘lower-quality’ protein such as cereals and grains in this comparison because they are not an ideal source of protein, especially in terms of their amino acid profile. But in a good balanced diet of legumes (peas, beans), tofu, nuts, and grains, you can certainly meet your protein needs.”

Still, eating less beef—and choosing chicken, eggs, and fish, which can have a “reasonably low,” carbon footprint—is better. “They can be part of a relatively low-carbon diet if eaten in moderation. This level of consumption though would be much lower than we currently see in most Western countries,” Ritchie adds. “So average consumption of meat would need to be reduced significantly; but for the small amounts we do eat, it’s best if we seek out options which are as ‘sustainable’ as we can.”

Those still aren’t as environmentally friendly as plant-based proteins, though. It may seem counterintuitive to buy internationally sourced beans at the supermarket rather than a cut of beef from your local farmer. We’ve been told to shop local and go zero waste, but ultimately, this research finds, the biggest environmental factor lies in what it took to produce those 100 grams of protein.

(28)