Tim Cook On Apple’s Future: Everything Can Change Except Values

In an exclusive Q&A, the current CEO discusses the Watch, how Steve Jobs informs Apple’s future, and how Apple lives “outside the box.”

Fast Company: How does Steve Jobs’s legacy live on at Apple?

Tim Cook: Steve felt that most people live in a small box. They think they can’t influence or change things a lot. I think he would probably call that a limited life. And more than anybody I’ve ever met, Steve never accepted that.

He got each of us [his top executives] to reject that philosophy. If you can do that, then you can change things. If you embrace that the things that you can do are limitless, you can put your ding in the universe. You can change the world.

That was the huge arc of his life, the common thread. That’s what drove him to have big ideas. Through his actions, way more than any preaching, he embedded this nonacceptance of the status quo into the company.

Several other things are a consequence of that philosophy, starting with a maniacal focus to make the best products in the world. And in order to build the best products, you have to own the primary technologies. Steve felt that if Apple could do that—make great products and great tools for people—they in turn would do great things. He felt strongly that this would be his contribution to the world at large. We still very much believe that. That’s still the core of this company.

There’s this thing in technology, almost a disease, where the definition of success is making the most. How many clicks did you get, how many active users do you have, how many units did you sell? Everybody in technology seems to want big numbers. Steve never got carried away with that. He focused on making the best.

That took a change in my own thinking when I came to the company [Cook left Compaq to join Apple in 1998]. I had been in the Windows world before that, and that world was all about making the most. It still is.

When Apple looks at what categories to enter, we ask these kinds of questions: What are the primary technologies behind this? What do we bring? Can we make a significant contribution to society with this? If we can’t, and if we can’t own the key technologies, we don’t do it. That philosophy comes directly from him and it still very much permeates the place. I hope that it always will.

Did that philosophy play out in the decision to make the Apple Watch?

Very much so.

Is that it, on your wrist?

Yes, it is. [Cook starts showing off different views on the watch.] See, my calendar is right here, there’s the time, the day, the temperature. There’s Apple’s stock price. This is my activity level for today. You can see what it was (March 18, 2015), and now it’s redrawing it for today. I haven’t burned very many calories today so far.

You look at the watch, and the primary technologies are software and the UI [user interface]. You’re working with a small screen, so you have to invent new ways for input. The inputs that work for a phone, a tablet, or a Mac don’t work as well on a smaller screen. Most of the companies who have done smartwatches haven’t thought that through, so they’re still using pinch-to-zoom and other gestures that we created for the iPhone.

Try to do those on a watch and you quickly find out they don’t work. So out of that thinking come new ideas, like force touch. [On a small screen] you need another dimension of a user interface. So just press a little harder and you bring up another UI that has been hidden. This makes the screen seem larger, in some ways, than it really is.

These are lots of insights that are years in the making, the result of careful, deliberate…try, try, try…improve, improve, improve. Don’t ship something before it’s ready. Have the patience to get it right. And that is exactly what’s happened to us with the watch. We are not the first.

We weren’t first on the MP3 player; we weren’t first on the tablet; we weren’t first on the smartphone. But we were arguably the first modern smartphone, and we will be the first modern smartwatch—the first one that matters.

The iPod was introduced in 2001 with fairly low expectations. When Apple introduced the iPhone in 2007, expectations were sky-high. Where does the watch fit in that continuum?

With the iPod, the expectations for Apple itself at that time were very low. And then most people panned the iPod’s price. Who wants this? Who will buy this? We heard all the usual stuff. On iPhone, we set an expectation. We said we’d like to get 1% of the market, 10 million phones for the first year. We put that flag in the sand, and we wound up exceeding it by a bit.

On the watch we haven’t set a number. The watch needs the iPhone 5, 6, or 6 Plus to work, which creates a ceiling. But I think it’s going to do well. I’m excited about it. I’ve been using it every day and I don’t want to be without it.

When the iPhone first came out, there weren’t any outside apps. Eighteen months later, because Apple opened the phone up to app developers, it was a completely different value proposition. What kind of curve do you expect for the watch?

As you said, developers were key for the phone. They were key for iPad, too, especially because they optimized apps for the tablet instead of just using a stretched-out smartphone app. And they’ll be key to the watch, too. Absolutely.

This time, of course, we understand their importance from the beginning. We released an SDK [software development kit] in mid-November. So by the time we ship the watch in April, there will be plenty of third-party apps. You don’t start with 700,000. You grow to that. But there will be enough apps to capture people’s imaginations.

Many people seem to have a hard time imagining the usefulness of the watch.

Yes, but people didn’t realize they had to have an iPod, and they really didn’t realize they had to have the iPhone. And the iPad was totally panned. Critics asked, “Why do you need this?” Honestly, I don’t think anything revolutionary that we have done was predicted to be a hit when released. It was only in retrospect that people could see its value. Maybe this will be received the same way.

You talked about the sense of limitlessness that Steve created. Part of that was the insistence on insane standards of excellence. He seemed to personally enforce that. Do you now play that same role, or is that kind of quality control more spread out?

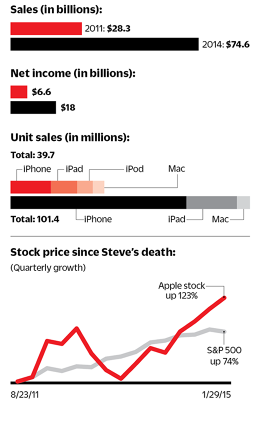

The truth is that it has always been spread out. Steve couldn’t touch everything in the company when he was here, and the company is now three times as large as it was in 2010. So do I touch everything? No, absolutely not. It’s the sum of many people in the company. It’s the culture that does that.

Steve was almost viewed from the exterior as the micromanager checking to make sure that every i was dotted, and every t was crossed, that every circuit was correct, that every color was exactly right. And yes, he made a lot of decisions. His capacity was unbelievable. But he was just one person—and he knew that.

It was his selection of people that helped propel the culture. You hear these stories of him walking down a hallway and going crazy over something he sees, and yeah, those things happened. But extending that story to imagine that he did everything at Apple is selling him way short. What he did more than anything was build a culture and pick a great team, that would then pick another great team, that would then pick another team, and so on.

He’s not given credit as a teacher. But he’s the best teacher I ever had by far. There was nothing traditional about him as a teacher. But he was the best. He was the absolute best.

Let me just make this one point. Last year, the company did $200 billion worth of business. We’re either the top smartphone maker in the world, or one of the top ones. Would the company have been able to do that if he were the micromanager that he was made out to be? Obviously not.

Steve’s greatest contribution and gift is the company and its culture. He cared deeply about that. He put in an enormous amount of time designing the concept for our new campus: That was a gift to the next generation. Apple University is another example of that. He wanted to use it to grow the next generation of leaders at Apple, and to make sure the lessons of the past weren’t forgotten.

Steve’s focus on the benefits of small teams has paid off for Apple. But maintaining the discipline to stay effective, fleet, and nonbureaucratic would seem to get harder and harder as Apple gets bigger and bigger.

And the rewards are greater and greater to do it right. So you’re right. It’s harder, and you are fighting gravity. But if you don’t feel like you’re in a small box, you can do it.

We’ve turned up the volume on collaboration because it’s so clear that in order for us to be incredibly successful we have to be the best collaborators in the world. The magic of Apple, from a product point of view, happens at this intersection of hardware, software, and services. It’s that intersection. Without collaboration, you get a Windows product. There’s a company that pumps out an operating system, another that does some hardware, and yet another that does something else. That’s what’s now happening in Android land. Put it all together and it doesn’t score high on the user experience.

Steve recognized early on that being vertical gave us the power to produce great customer experience. For a long while, that was viewed as crazy logic. More and more people have opened their eyes to the fact that he was right, that you need all those things working together.

Steve always said that the difference between Apple and other computing companies was that Apple made “the whole widget.” At first, that meant making the hardware and software for a computer, or for a device like the iPod. But now the “widget” is bigger. It’s become the whole “Apple experience,” meaning the universe of iPhones, iPads, and Macs, and now the watch, trying to work seamlessly with cloud services, content from any number of musicians and filmmakers and video producers, and so on. It’s one big mother of a widget. Is it really manageable, or are we beginning to see cracks, because there’s just so much to maintain across so many different interfaces? Microsoft ran into the same problem when it tried to be all things to all people with its operating system.

I think it’s different. Part of the reason Microsoft ran into an issue was that they didn’t want to walk away from legacy stuff.

Apple has always had the discipline to make the bold decision to walk away. We walked away from the floppy disk when that was popular with many users. Instead of doing things in the more traditional way of diversifying and minimizing risk, we took out the optical drive, which some people loved. We changed our connector, even though many people loved the 30-pin connector. Some of these things were not popular for quite a while. But you have to be willing to lose sight of the shore and go. We still do that.

So no, I don’t accept your comparison to Microsoft. I think it’s totally different. Yes, things are more complex. When you’re doing a Mac, that’s one thing. But if you do a phone, and you want to optimize so that you have the fewest dropped calls of anyone, and you’re working with 300 or 400 carriers around the world, each with slightly different things in their network—yes, that’s more complex.

It’s more complex to do things like continuity. Now the customer wants to start an email on their iPhone and complete it on their iPad or Mac. They want a seamless experience across all of the products. When you’re only doing a Mac, that seamless experience is a party of one. Now you’ve got a three-dimensional thing, and the cloud. So it is more complex. There’s no doubt.

What we try to do is hide all of that complexity from the user. We hide the fact that doing this is really tough, hard engineering so that the user can go about their day and use our tools the way they would want and not have to worry about it. Sometimes we’re not perfect with that. That’s the crack that you’re talking about. Sometimes we’re not. But that, too, we will fix.

In my mind, there is nothing that’s incorrect about our model. It’s not that it’s not doable, it’s that we’re human sometimes, and we make an error. I don’t have a goal of becoming inhuman, but I do have a goal of not having any errors. We’ve made errors in the past, and we’ll never be perfect. Fortunately, we have the courage to admit it and correct it.

But, still, you are fighting gravity. You don’t fear that this will become too big a job?

No, because we don’t live in the box. We are outside of that. What I see is that we have to continually have the discipline to define the problem so that it can be done. If you try to engineer to the complexity, then it does become the impossible dream. But if you step back and think about the problem differently, think about what you’re really trying to do, then I don’t think it becomes an impossible task at all.

By and large, I think we’re proving that. Look at the App Store, where we’re doing things on an unparalleled scale—there are a million and a half apps on the store. Would anybody have guessed that a few years ago? We are still curating those apps. Our customers expect us to do that. If they buy an app, they expect it to do what it says it does.

Are there any fundamental ways in which you are letting go of parts of Steve’s legacy?

We change every day. We changed every day when he was here, and we’ve been changing every day since he’s not been here. But the core, the values in the core remain the same as they were in ’98, as they were in ’05, as they were in ’10. I don’t think the values should change. But everything else can change.

Yes, there will be things where we say something and two years later we’ll feel totally different. Actually, there may be things we say that we may feel totally different about in a week. We’re okay with that. Actually, we think it’s good that we have the courage to admit it.

Steve would do that all the time.

He definitely would do that all the time. I mean, Steve was the best flipper in the world. And it’s because he didn’t get married to any one position, one view. He was married to the philosophy, the values. The fact that we want to really change the world remains the same. This is the macro point. This is the reason we come to work every day.

Are you looking forward to Apple’s new campus? [The company is set to move into massive new headquarters in 2016.] Would you have created this kind of campus if you had been CEO when the decision was first made?

It’s critical that Apple do everything it can to stay informal. And one of the ways that you stay informal is to be together. One of the ways that you ensure collaboration is to make sure people run into each other—not just at the meetings that are scheduled on your calendar, but all the serendipitous stuff that happens every day in the cafeteria and walking around.

We didn’t predict our employee growth, so we haven’t had a campus that houses everyone. We are spread out in hundreds of buildings, and none of us like that; we hate it. Now we’ll be able to work primarily at that one campus. So, yeah, I’m totally behind that.

As the human scale of the company grows, as the generations churn and new people come in, how does the culture get transferred to new employees? Is there something that needs to be systematized?

I don’t think of it as systematizing, but there are a number of things that we do, starting with employee orientation. Actually, it starts before that, in interviews. You’re trying to pick people that fit into the culture of the company. You want a very diverse group with very diverse life experiences looking at every problem. But you also want people to buy into the philosophy, not just buy in, but to deeply believe in it.

Then there’s employee orientation, which we do throughout the company all over the world. And then there’s Apple U., which takes things that happened in the past and dissects them in a way that helps people understand how decisions were made, why they were made, how successes occurred, and how failures occurred. All of these things help.

Ultimately, though, it’s on the company leaders to set the tone. Not only the CEO, but the leaders across the company. If you select them so carefully that they then hire the right people, it’s a nice self-fulfilling prophecy.

I noticed you still have Steve’s nameplate up next to his old office.

Yeah.

Why? And will you have anything like that over at the new place?

I haven’t decided about what we’ll do there. But I wanted to keep his office exactly like it was. I was in there with Laurene [Powell Jobs, Steve’s wife] the other day because there are still drawings on the board from the kids. I took Eve [Steve’s daughter] in there over the summer and she saw some things that she had drawn on his white board years earlier.

In the beginning I really didn’t personally want to go in there. It was just too much. Now I get a lot more appreciation out of going in there, even though I don’t go in very often.

What we’ll do over time, I don’t know. I didn’t want to move in there. I think he’s an irreplaceable person and so it didn’t feel right . . . for anything to go on in that office. So his computer is still in there as it was, his desk is still in there as it was, he’s got a bunch of books in there. Laurene took some things to the house.

I don’t know. His name should still be on the door. That’s just the way it should be. That’s what felt right to me.

[Photo: Pete Marovich, Getty Images]

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(292)