Trump’s Panama Problem

It was a big moment for Donald Trump.

On July 6, 2011, the future president was beaming as he celebrated the opening of his first international real-estate deal, the Ocean Club in Panama City, Panama. The flashy hotel-condo complex featured a 72-story tower that transformed the skyline of the city with its sail-shaped design. After a ceremony featuring dancers in traditional Panamanian dress, Trump stood at a podium, flanked by his two oldest sons, Don Jr. and Eric, paused during his remarks, gently leaned over and offered a special thanks to Ricardo Martinelli, the president of Panama.“You’re my friend. Great honor.”

Standing next to Trump’s children, Martinelli smiled back. The white-haired, stocky president was flattered, proud of the fact that the complex had the potential to transform his small country into a destination for the rich and famous. As they both delivered their remarks that afternoon, the sky broke open and a torrential rain flooded the streets, turning the peninsula on which the complex stood into a “swamp island.” Trump and Martinelli had to ride out through the flooded streets in their separate chauffeured SUVs.

More than five years later, Trump has taken over the Oval Office and Martinelli is a fugitive from justice wanted on multiple corruption charges and investigations, ranging from allegedly helping to embezzle $45 million from a government school lunch program to insider trading to using public funds to spy on more than 150 political opponents, lawyers, doctors, and activists. But their paths could intertwine again very soon in what may be a thorny dilemma for the Trump administration. At the end of September, Panama’s Supreme Court asked the United States to extradite Martinelli, who left office in 2014 and now lives in exile in a luxury waterfront condo in Miami.

While the United States has codified policies to deny visas to foreign officials facing criminal charges in their home countries, and Trump’s recent executive order on immigration enforcement targets for removal individuals with even unresolved criminal charges, Martinelli entered the U.S. in 2015 on a visitor visa as the criminal investigations around him and his inner circle were tightening and has reportedly remained since.

Before fleeing Panama, Martinelli sat on the board of a bank that became the co-trustee for the Ocean Club, a role that left it in charge of managing funds coming in from rentals and sales, and of disbursing money to Trump, who gets millions in fees from the project. The Ocean Club has been Trump’s largest individual source of branding fees, reports the Economist, earning Trump “at least $50 million on the project on virtually zero investment,” reported the Washington Post in January.

Now, the extradition request highlights the potential conflicts of interest that have swirled around Trump: A decision that is usually made on the merits by career diplomats could be complicated by the president’s personal and business ties to Panama. Officials at the State Department could be inclined to approve the extradition, mindful of not antagonizing the current government of Panama, which exerts plenty of influence over the fate of a development that makes millions for the president’s family—or to decline the request out of their awareness of Martinelli’s support for the Ocean Club and his admiration and kind words for Trump.

How Global Deals Could Complicate Diplomacy

The Panama skyscraper was the first building outside of America to bear the Trump name, in a licensing and management deal with local development company Newland International Properties. Trump’s companies today “have business operations in at least 20 countries, with a particular focus on the developing world, including outposts in nations like India, Indonesia, and Uruguay,” according to the New York Times. An analysis of Trump’s global deals published on January 25 by the Washington Post found that the Trump name has been contracted out “to at least 50 different licensing or management deals.” As the Post explained, “for his international projects, he has done a majority of his work through licensing—where a developer who is liable for the actual cost and responsibility of the contract uses Trump’s name for their hotels. This allows Trump to spread his brand and image worldwide without actually being liable for the project.” (In addition to real estate projects, Trump has also licensed his name in branding deals for a variety of consumer products such as Trump Vodka, Trump Steaks, and Trump Menswear.)

Trump has done branding deals ranging from a suite of private mansions in the United Arab Emirates, a luxury resort and golf course in Indonesia, a since-halted project in Azerbaijan that nevertheless earned him more than $2.5 million in fees, and a number of projects in India, where the Times found he had more projects in the works than anywhere else outside of North America. Several of the Trump projects in India “are being built through companies with family ties to India’s most important political party,” reported the Times. In the Philippines, Trump’s partner in a $150 million tower in Manila was named a special envoy to the United States in October by Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte, whose war on drugs has involved the summary execution of thousands of suspected drug users and sellers.

Michael H. Fuchs, who until recently helped to oversee American relations with the Philippines as deputy assistant secretary of state, explained to the Times that “the biggest gray area may not be a President Trump himself advocating for favors for the Trump Organization. It’s the diplomats and career officers who will feel the need to perhaps not do things that will harm the Trump Organization’s interests. It is seriously disturbing.”

Ethics experts have raised concerns about the potential for these global deals to complicate international diplomacy and whether Trump will weigh his political actions against their impact on his business allies. Another concern is that foreign officials might take actions to benefit Trump’s local business in order to curry favor with the White House.

“America has been treated to reports of multi-billion-dollar projects across the planet, to photos of Mr. Trump glad-handing businessmen and to images of exotic, Trump-branded buildings standing like monuments to the decay of American ethics,” noted the Economist in November.

Despite his global financial entanglements, as Trump and his inner circle have repeatedly emphasized, the conflict of interest laws that restrain other federal employees don’t apply to the president. “As you know, I have a no-conflict situation because I’m president, which is—I didn’t know about that until about three months ago, but it’s a nice thing to have,” Trump said at his January 11 press conference. Days after his inauguration, a group of ethics lawyers filed a lawsuit against Trump claiming that his holdings violate the Constitution’s emoluments clause, which bars federal officials from taking payments from foreign governments. Trump also hasn’t released his taxes or a list of his lenders, obscuring a complete picture of his potential global conflicts.

Though Trump announced at his January 11 press conference that he would not pursue additional foreign deals while in office and that he would move his assets into a trust controlled by his children, income from the Panama project will continue to roll in.

And that makes for a potential ethical conflict for the president. As the Wall Street Journal noted recently, “if the U.S. were to get into a dispute with [Panama] during the Trump administration, it might appear that his desire to maintain this revenue stream might influence his decision making.”

International extradition requests involve both executive and judicial processes, as the State Department receives the initial request from the foreign government in question and decides if it should be passed on to the Justice Department. If it is, and an ensuing court process finds the subject of the request to be extraditable, the case goes back to the Secretary of State, who is vested with the final decision-making power over whether to authorize the extradition. As explained in a recent article in Law360 co-authored by former Justice and State Department lawyers, “the Secretary of State has ultimate discretion to determine whether the subject should be released or surrendered. In making this decision, the Secretary may take into account ‘any humanitarian or other considerations for or against surrender,’ as well as ‘written materials submitted by the fugitive, his or her counsel, or other interested parties.’”

While the Secretary of State and the executive branch are unlikely to get involved in requests to extradite the average alleged criminal, an extradition request for a former head of state will inevitably become tangled with international politics and diplomatic concerns. “It would have to get red-flagged,” says John Parry, a professor of law at Lewis & Clark Law School who has worked on extradition cases. The United States generally tries to handle the average extradition request from close allies reasonably expeditiously through the judicial system, but for “the ones that have a diplomatic or political or foreign relations angle” like a former head of state like Martinelli, Parry explains, “the political people are going to want to be involved in some way, they just are.”

If the subject of such a high-profile extradition request were a friend or associate of the president, Parry says you’d expect the president to recuse himself from the decision-making process, even instructing their Attorney General and Secretary of State not to discuss the request with him. “If the president were to get directly involved or if the president’s close advisors on behalf of the president got directly involved with the extradition, sure that would raise a conflict of interest question, I think it definitely would,” says Parry.

The Trump administration hasn’t commented on the extradition request or whether the president has been in contact with Martinelli since his election, despite repeated requests from Fast Company. Shortly after his election victory, Trump had a phone call with current Panamanian president Juan Carlos Varela, who was Martinelli’s vice-president during his 2009-2014 term, with whom he reportedly discussed regional security, commerce, and the fight against organized crime and drug trafficking. It is unclear whether they also discussed the extradition request, and Panamanian officials declined to tell Fast Company if the two leaders discussed the fate of Martinelli. When asked about the current status of the request, a spokeswoman for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs would only say that the process is in American hands. President Varela’s office did not respond to requests for comment. The U.S. Justice Department doesn’t comment on extradition requests as a matter of policy. (On February 19, Trump called Varela for another conversation about shared security concerns, and invited him to visit Washington in the months ahead.)

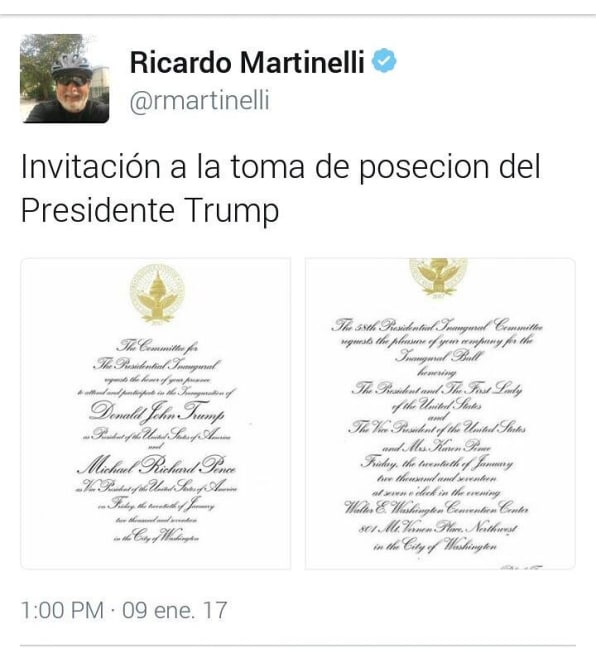

Despite all of his troubles in Panama, Martinelli seems confident that he remains in Trump’s good graces. The day after Trump’s victory, Martinelli tweeted his congratulations on the “triumph,” adding “God bless America.” And days before Trump’s inauguration, Martinelli tweeted an image of what he described as an “invitation” to the official Trump-Pence Inaugural Ball. (A few minutes later, after Twitter users in Panama took notice, he deleted the tweet and didn’t mention the inauguration again until the day of the ceremony, when he tweeted about what a beautiful city Washington was and how many people were in town for the event, posting similar sentiments on Facebook.) It’s not clear if Martinelli actually attended the inauguration or the inaugural ball and his spokesman declined to tell Fast Company whether the former president has been in touch with Trump or his staff since the U.S. election.

“We’ll do anything to support Trump in their mission.”

Soon after Martinelli took office in 2009, Trump became one of his biggest fans. Though there were already news reports detailing the Panamanian president’s “lack of commitment to ‘rule of law,’” per diplomatic cables released by WikiLeaks in 2010, Trump anointed the Latin American leader a “great president” in 2011 and cheered the businessman-turned-politician’s corporate style. “Frankly, we need some of that in the United States,” he told the Christian Science Monitor in Panama City after inaugurating the Ocean Club. He lionized Martinelli as a “businessman with heart,” whose leadership in Panama showed Trump “that’s why the United States is doing so poorly, because it’s not being run properly, it’s not being run as a businessman would,” he told the Monitor.

That summer, Trump’s opening of the mixed hotel and condo development on Panama City’s waterfront to which he’d licensed his name and that his management company would run marked a new frontier in his ambitions. With his name recognition exploding due to his successful TV show, The Apprentice, and dogged by a mixed record at home with some high-profile U.S. projects ending up in foreclosure or unfinished, Trump’s decision to license his name overseas was a smart move. In Martinelli’s remarks at the Ocean Club’s opening event, he lavished praise on Trump, thanking him for “allowing this wonderful building to have his name,” toured the hotel with him, told Trump that “everything you touch turns to gold,” and invited him to go sport fishing.

Eric Trump told the crowd at another opening event in July 2011 that “first it takes an unbelievable government and you just heard it—‘We’ll do anything to support Trump in their mission.’ It’s not often that you hear governments say that and it’s such a relief to come into a country that’s so pro-development.”

It was the Trump Organization’s first international real estate deal, “the one by which the rest will be benchmarked,” as Eric put it. Ivanka explained in an earlier interview with the Monitor in February 2011 that “this building is a very important bridge for us as we begin to expand internationally, not just through South America, but the world.”

Trump posing with Ocean Club staffers and associates during the development’s opening ceremony in Panama City on July 6, 2011.

Despite initial fears that Trump’s inflammatory campaign rhetoric might hurt his brand, by the time he was elected president buyers were eagerly snapping up Ocean Club units in a rush—the last of the developer-controlled condos were sold at the end of 2016. The project’s developer Newland International Properties had noted under “Risk Factors” in an October 2015 debt offering document that Trump’s campaign “may negatively impact potential buyers’ perceptions of Trump Ocean Club.” But the concerns turned out to be unfounded, as “demand spiked in the weeks following Mr. Trump’s election, with buyers betting that the Trump brand will surge in value,” noted the managing director of Punta Pacifica Realty, a local sales and management company that handled many of the final deals and tracked Ocean Club sales data. In a recent press release titled “New Interest for Trump Project in Panama City,” he wrote that “since the election, PPR has seen the trend continue, with inquiries high as potential buyers investigate the impact of the Trump Effect on the building’s values.”

When The Trumps First Met Martinelli

The Trump family first met Martinelli back in 2006, when Ocean Club developer Roger Khafif invited him to an early meeting with Ivanka, Eric, Donald Jr., and a handful of local government representatives including the mayor of Panama City. “I was friends with Ricardo from way before he became president,” Khafif says, adding that he’s “known him for the last 20 years or so.” “Panama is a small country, everybody knows everybody,” Khafif says, describing that early 2006 meeting with Martinelli as more of a social networking event. Martinelli was then a prominent businessman who owned one of the biggest and most visible companies in Panama, the supermarket chain Super 99, and was also the leader of the pro-business Cambio Democrático party.

Khafif says that he had previously sold Martinelli an apartment at a smaller resort project that he’d worked on in the past, but wasn’t aware of any stake that Martinelli may have acquired in the Ocean Club.

Still, in the small world that is Panama, Martinelli’s interest in the hotel was not just personal. He was a director of Global Bank, one of the largest banks in the country, whose subsidiary Global Financial Funds became the co-trustee for the project a couple of years after the complex opened in 2011. Global Financial Funds replaced the previous co-trustee, HSBC’s Panama unit, in 2013, the same year that HSBC sold its Panamanian assets to a Colombian bank. Khafif says that Global Bank was “a bank we used to work with” before signing them on in 2013, and insisted that Martinelli “had nothing to do with” the bank’s role as co-trustee of the Ocean Club.

As co-trustee, Global Financial Funds gained a view into the project’s books and buyers, and was “supposed to make sure money was spent the right way,” as Khafif puts it. Global Financial Funds was responsible for receiving funds coming in from rentals and sales accounts and for transferring it to a disbursement account, after having reserved or paid Trump’s commission for the licensing of his name. As co-trustee, Global Financial Funds was also given custody of certain collateral related to the Ocean Club, such as the original stock certificates.

Global Bank, where Martinelli’s son Ricardo (Rica) also became a director and his wife has been listed as an alternate director, was recently singled out by the Times as being “one of three Panamanian banks whose outlook was recently revised by S & P Global to negative from stable, reflecting ‘shortfalls in regulation, supervision, governance, and transparency in the Panamanian financial system.’”

Global Bank declined to tell Fast Company if Martinelli still serves on the bank’s board or in any other capacity. There is still a Ricardo Martinelli listed on the board of Global Bank subsidiary Global Valores, which offers investment products and services, on the company’s website. (A few hours after Fast Company reached out to Global Bank and the former president’s son Rica, the bank’s webpage listing this Martinelli on the board began redirecting to another part of the company’s website.)

Corruption, Bullying, And Blackmail

The Trumps’ admiration of Martinelli appeared to be unaffected by the cascade of international news about his increasingly authoritarian and vindictive behavior, blown open by WikiLeaks’ 2010 release of U.S. diplomatic cables, in the year before the family publicly heaped praise on him. Mainstream news outlets like the Times covered these revelations published by WikiLeaks—one of Trump’s favorite sources during the U.S. election—about Martinelli in great detail starting in late 2010. According to the cables, Martinelli ruled by “bullying and blackmail,” and had threatened to stop cooperating with the United States unless American officials helped him with a wiretapping program. The cables documented U.S. Embassy officials in Panama sounding red alarms over Martinelli beginning as early as the second week of his 2009-2014 administration. That’s when, as McClatchy noted, the U.S. Ambassador to Panama presciently warned that he was “almost certain to spell trouble for Panama’s democratic institutions.”

Panama’s anti-corruption czar Angélica Maytín Justiniani said that the amount lost to corruption in Martinelli’s administration is “possibly in the billions of dollars,” and that “it’s obvious that a lot of the money is outside Panama,” McClatchy reported in 2015. She added that “we’re learning of midlevel [former] officials who have assets of $25 million and 10 properties. We never saw anything like this, even under the military dictatorship.” A Panamanian law professor and human rights activist concurred in an interview with NPR that Martinelli “did more harm to the country than even the dictatorships of the last century,” as “even the militaries, they were not able to develop the degrees and the practice of corruption like Martinelli did.”

Trump’s previous statements implying that overseas corruption was just another cost of doing business suggest that the allegations wouldn’t have raised many red flags anyway. When Walmart’s massive Mexican bribery scandal broke in 2012, Donald Trump said that the U.S. anti-bribery law that applies internationally, the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, is a “horrible law and it should be changed.” “Every other country in the world is doing it and we’re not allowed to. It puts us at a huge disadvantage…the world is laughing at us,” he said.

A glimpse into the magnitude of that alleged corruption was revealed in federal court in Brooklyn in December, where Latin America’s largest construction company, Odebrecht, pleaded guilty in a case brought by officials in the United States, Brazil, and Switzerland involving a global bribery scheme spanning a dozen countries. Panama’s current government says that the Martinelli administration was the recipient of Panama’s share of these bribes (Martinelli’s sons have denied any involvement to the local press). On January 12, Panama’s attorney general said that Odebrecht had agreed to pay the Panamanian government more than $59 million in reparations for the bribes it allegedly paid to secure contracts between 2010 and 2014, while Martinelli was president. “The sum is the amount in bribes Odebrecht admitted paying to officials and intermediaries there in a plea agreement disclosed in December in a U.S. court,” Reuters reported. Odebrecht, along with its affiliated petrochemical firm, would pay at least $3.5 billion in penalties in the global case, the biggest penalty ever for a violation of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, reports the Times.

At the end of January, Panama charged and ordered the investigation of 17 people in the Odebrecht bribery case, reportedly including Martinelli’s sons Rica and Luis Enrique. And on February 14 their government said thatInterpol had issued international “red notices” for Martinelli’s sons Ricardo (Rica) and Luis Enrique in the Odebrecht case, at the request of Panama’s anti-corruption prosecutor. Some of the money was allegedly laundered through Swiss bank accounts, and such Martinelli-controlled accounts containing $22 million were reportedly frozen in the process, according to Univision.

Since fleeing Panama, Martinelli has blamed his troubles on “rigged” circumstances engineered by political enemies who are a threat to his life. In response to the Panamanian Supreme Court’s ruling demanding his detention to face the charges against him, Martinelli wrote in a letter in late 2015 that “like those now detained illegally, I’m a victim of rigged proceedings, of coerced or manufactured witnesses and it is ever more evident the violations to the presumption of innocence and due process.”

Martinelli is just one of several foreign leaders suspected of corruption abroad who have found refuge in the United States. There are explicit government policies “designed to keep the United States from becoming a haven for corrupt officials,” but a number of such officials fleeing their legal systems back home “have slipped through the cracks,” reported ProPublica in a recent article co-published with the Miami Herald, calling Martinelli “one of the most prominent cases.” Proclamation 7750, issued by George W. Bush in 2004, has the force of law and instructs the State Department “to ban officials who have accepted bribes or misappropriated public funds when their actions have ‘serious adverse effects on the national interests of the United States.’” Under these rules, U.S. officials “do not need a conviction or even formal charges to justify denying a visa,” and can do so “based on information from unofficial, or informal sources, including newspaper articles,” noted ProPublica.

In response to the article, Martinelli’s spokesman released a letter declaring that “it is wrong to say that former President Martinelli is in the United States to avoid facing these political processes. Actually having no accused status and haven’t not being [sic] formally charged, he has faced each of this [sic] processes through his attorneys as granted by our laws and constitution.” Martinelli’s letter claimed that “in Panama his life is threatened by the political persecution of President Juan Carlos Varela,” and even accused the current administration of using “torture” to extract false accusations against him. Martinelli’s team added that “there is no documentary evidence or material that links former President Ricardo Martinelli in the alleged facts.”

Despite several requests for comment, Martinelli declined to be interviewed for this story.

The American Martinelli

Trump and Martinelli’s mutual affection seems to be partly based on their status as wealthy men with political ambitions who appear to be unmoved by concerns over conflicts of interest. By 2015, Martinelli’s net worth had risen to $1.1 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index. Aside from Super 99, he has other large holdings in media, real estate, banking, energy, and sugar, and owns a plane, two helicopters, and a yacht, according to Bloomberg. Martinelli was elected on the promise that he would run Panama as he ran his businesses. With his election in 2009, he had perfected the style of right-wing populism that Trump is selling to Americans today. Martinelli’s massive personal wealth, the campaign sales pitch went, made him the only outsider immune to influence and able to dismantle an entrenched and corrupt political establishment.

Trump’s campaign was so resonant with Martinelli’s that many Panamanians today refer to Trump as the “American Martinelli.” They even shared the same political operative, Republican strategist Alex Castellanos, who worked on Martinelli’s campaign in 2009 and guided a pro-Trump super PAC in 2016. Castellanos, a high-profile political and corporate consultant, appeared regularly on Meet the Press and CNN during the campaign as a Trump supporter (though he was a Trump critic before the nomination).

Castellanos has said that the now-fugitive leader, whom he referred to as “Panama’s version of Italy’s Silvio Berlusconi,” “was politically incorrect on the good days, ragingly out of control on others.” As with Trump, “we couldn’t hide his affluence so we celebrated it,” Castellanos explained, adding that “we used his wealth without apology, as inspiration for every Panamanian’s success.”

“One Of the Most Beautiful Buildings In The World”

The Trump Ocean Club tower that Martinelli helped to inaugurate in 2011 was heralded as the icon of Panama City’s rapidly expanding skyline–50 skyscrapers have been built around the crowded shoreline since 2007. (There is also one of Martinelli’s Super 99 supermarkets just a few blocks from the Ocean Club, to which the complex offers free shuttle service.)

The Ocean Club’s official website explains that the goal was to build “the most spectacular development in Panama’s history,” and Trump called it “one of the most beautiful buildings in the world.” Trump tweeted that the building had become “Central America’s architectural icon,” announcing that “excellence has arrived to So. America.” The Ocean Club was supposed to be a kind of Elysium on the isthmus for rich expats drawn to Panama for its relaxed tax and immigration laws, and one of “the best retirement programs in the world,” according to its promotional material. Ivanka Trump explained to the Latin Business Chronicle that Panama’s incentives were “incredibly luring to international [investors], especially as we in America are being taxed to the hilt.” Ocean Club condo units are exempt from property taxes through 2031.

Panama’s long-term global strategic importance, due to the Panama Canal connecting the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, has also helped reassure Ocean Club buyers that the region has some degree of economic stability. Today, a third of trade coming from Asia to America passes through the canal. The country has been the key passageway for interoceanic trade going back hundreds of years to the days of the Spanish Empire, when South America’s resources like the gold and silver of the Inca empire were shipped to Spain via Panama. Martinelli had also served as chairman of the board of directors of the Panama Canal Authority and as minister of Canal Affairs from 1999 to 2003.

Trump famously outraged many Panamanians in the year before the Ocean Club opening, when he lamented that the canal had just been given back to the Panamanian people. “We gave it to Panama. We didn’t say, here, take us, pay us $100 billion over a 10-year period or 50-year period. Who are these people that are making these decisions? So, we have very bad decision-makers in this country. And this country didn’t get great by having decisions like that made,” Trump told Wolf Blitzer in 2010. In response, Panama City councillors voted unanimously to declare Donald Trump “persona non grata” in March 2011, just months before his project’s grand opening there. Panama’s Commerce and Industry Minister Roberto Henriquez said that “somebody who has 400 million dollars invested in Panama should not speak this way,” and that “I think it was a political stupidity on the part of Donald Trump,” AFP reported. After the backlash, Trump issued a rare conciliatory statement and spoke to Panamanian press, insisting that he was simply criticizing the negotiating abilities of American politicians and that “if I were from Panama, I’d try and make the same kind of a deal, I respect that.” “I paid Panama a great compliment,” he explained.

To reduce the bottleneck effect at its gates as shipping traffic and the size of container ships increased over the years, Panama announced plans for a $5.2 billion expansion of the canal in 2006—on the same day that the Trump Ocean Club was launched in New York City. The canal expansion was another important marketing tool for the development, signaling Panama’s continued economic desirability. “Panama is amazing. It’s thriving. You know why? The canal is doing so well, and they’re now expanding the Panama Canal,” Trump told CNN. “Home to the number one shipping and trade canal in the world,” Ocean Club promotional material explained.

Panama’s location connecting South and Central America—and the vast, swampy and notoriously lawless Darién Gap border region with Colombia—has also raised persistent security concerns since it has served as a key conduit for smuggling for decades. Former U.S. Ambassador Barbara Stephenson noted the arrest of Martinelli’s second cousin Ramon Martinelli in Mexico for his role in a drug smuggling ring that was transporting up to $30 million a month through Panama’s Tocumen International Airport, McClatchy noted. President Martinelli later told Stephenson, according to the cable, that Ramon was the “black sheep” of the family and that his government would have arrested him if Mexico didn’t.

Panama’s status as a nexus of drug smuggling, money laundering, and strategic importance were notoriously embodied in former Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega, a paid CIA asset whose nefarious activities prompted President George H. W. Bush to launch Operation Just Cause, the invasion of Panama in late 1989 that involved tens of thousands of U.S. troops. Noriega was under indictment in Florida on drug trafficking charges before the invasion, and after his capture and arrest in Panama, he was taken back to the United States and sentenced to 40 years in prison (later reduced to 30) on drug trafficking, money laundering, and racketeering charges. He was the first foreign head of state to be convicted on criminal charges in a U.S. court. (In 2010, Noriega was extradited to France on further money laundering charges, where he received a seven-year sentence, but in 2011 was extradited back to Panama to serve a sentence there for the murder of opponents during his rule.)

While Trump constantly raged against “globalists” during his presidential campaign, the Ocean Club was meant to be a magnet for precisely the kind of borderless flow of money that he now loves to criticize. (Panama also has the second-largest free-trade zone on Earth, after Hong Kong, a fact highlighted in the Ocean Club’s sales pitch.) Panama has been a pillar of globalization for hundreds of years, in recent decades known as one of the world’s premier “money laundries” for its facilitation of opaque international financial transactions and corporate confidentiality laws. (The new government of Panama says that it is implementing greater transparency laws, though as President Varela admitted to the Times last year, “under previous governments, Panama was no doubt a target of money launderers.”)

Real estate in Panama City was booming in part because of all the dirty money flowing in from around the world. As a U.S. Embassy cable from 2007 released by WikiLeaks noted, “ultimately, real estate projects financed by the proceeds of criminal activity distort the market for legitimate developers and create excess supply, which may be why 20,000 luxury apartments are projected to be available in Panama City between now and 2010.” Pointing out the city’s noticeably dark skyline, photographer Paolo Woods told the Times in 2015: “What’s amazing is most of the skyscrapers are dark,” adding that “they’re just there to launder money.”

As the BBC put it in 2014, “the Russian mafia is believed to control some prime real estate in Panama City while the Sinaloa Cartel— perhaps the most powerful drug-trafficking organization in the world—brings its cocaine from Colombia via Panama on its route north.”

Some international buyers of Trump Ocean Club units were assisted by Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca with the creation of accompanying offshore shell companies set up to facilitate those purchases, according to emails released in last year’s infamous Panama Papers leak. One of the firm’s principals, Ramon Fonseca, also served as an advisor to then-President Martinelli. On February 9, Fonseca and the co-head of the firm, Jürgen Mossack, were taken into custody and denied bail by Panamanian authorities as part of the government’s investigation into the Odebrecht bribery scandal. The firm is just one of many other law firms and lawyers who assisted buyers of Trump Ocean Club units with creating such offshore entities, according to Panamanian corporate records. The leaked emails show the Ocean Club development company’s COO initiating contact with and offering to cover travel expenses for Mossack Fonseca lawyers, McClatchy reported.

(Panamanian shell companies have also been a popular vehicle for buyers of luxury Trump properties back home. As Forbes reported in a story about money laundering in 1986, “once the money enters the banking stream through shady banks, it is indistinguishable from other money. For example, fully one-third the apartments in Manhattan’s super-expensive condominium Trump Tower are owned by foreign corporations, mostly from Panama and the Netherlands Antilles.” Among these Panama-routed early Trump funds were those of Haitian dictator “Baby Doc” Duvalier, who famously acquired a foothold in Trump Tower in 1983, the year it opened, when his very close friend and family decorator purchased a unit. The condo, then worth $1.65 million, was paid for under cover of a Panamanian shell company, according to a 1986 lawsuit filed in the U.S. by the Haitian government.)

While marketing the Ocean Club to the global jet set crowd, the building’s sales team put extra emphasis on Russian investors looking to park cash overseas, and held Russian marketing events around the world from Moscow to Mar-a-Lago. As the Times put it in an examination of Trump’s Russian forays on January 16, “he discovered that his name was especially attractive in developing countries where the rising rich aspired to the type of ritzy glamour he personified.” Panama City became one of the preferred Trump projects for Russian investors looking to move their money offshore, offering a more affordable South Florida-type lifestyle with relaxed tax and immigration laws, and stable property rights. (The Trump brand also became popular in places like “Little Moscow” in South Florida, where as the Post reported in November, “Russians helped Donald Trump’s brand survive the recession.”) As the Trump Organization’s chief counsel told the Post, “there’s newfound wealth in Russia,” and “any developer is going to where you have a chance of selling your product.”

The “newfound wealth” that he was referring to included the vast amounts of cash that had long been pouring out of Russia’s chaotic post-Soviet economy, capital flight that is today estimated to have exceeded $1 trillion. This newfound Russian wealth became a valued part of the Trump Organization’s sales of condos, with Donald Trump Jr. noting in 2008 that “Russians make up a pretty disproportionate cross-section of a lot of our assets. We see a lot of money pouring in from Russia.”

Aside from global players, the Trump Ocean Club also became a favorite of Panama’s domestic elite, and hosted a number of high-profile Martinelli-attended events. Wharton’s Global Forum Panama featured a one-on-one discussion with Martinelli, and he attended Forbes magazine’s launch party for its Central American edition as a VIP guest. “Panamanians still talk about the lavish wedding of Martinelli’s private secretary, Adolfo ‘Chichi’ de Obarrio a year later [in 2013] at the luxury Trump Ocean Club,” attended by Martinelli and members of the ruling party, reported McClatchy in early 2015. The reporter noted that “de Obarrio, who hadn’t yet turned 30, was gatekeeper for nearly all government purchases and a friend of Martinelli’s son,” and that his wedding at Trump’s Ocean Club featured a “massive fireworks display.”

As the criminal investigations around his inner circle started to close in in early 2015, Martinelli fled Panama for his waterfront luxury condo in Miami, in a 20-story building made famous for its appearances in Scarface and on Miami Vice. Later that year, he set up a Florida company called White Shark Developments LLC. A few days after its incorporation, he tweeted that a visa was required to stay in the United States for up to 180 days, unless you invest at least $500,000 to get an investor visa.

Martinelli has remained an active presence on Twitter from his American sanctuary, where he has denied all wrongdoing. In an interview with Bloomberg reporters at a Miami cafe in 2015, he said that his political opponents “are so afraid of my tweets,” warning, “look what happened in the Arab Spring.” Martinelli was stripped of his immunity to criminal prosecution in 2015, and at the end of September the government of Panama asked the United States to extradite him to face the corruption and illegal spying charges.

Ocean Club Condo Owners To Trump’s Team: You’re Fired

Back in Panama, the Trump Ocean Club had its own legal meltdown. In 2010, Trump said that the units were “selling like hotcakes.” But just a few months after the tower’s 2011 inauguration, the project’s developer defaulted on the debt and later declared bankruptcy. By 2015, the condo owners voted to fire the Trump management team, citing “more than $2 million in unauthorized debts, paying its executives undisclosed bonuses, and withholding basic financial information from owners,” reported the Associated Press.

The condo owners’ board said that the Trump team had pulled all of this off by what the AP described as “fine print chicanery.” Trump’s management company refused to accept being fired, then announced that it was quitting and demanded a $5 million termination fee. The AP then broke the news a month later that Trump had filed a confidential claim with the Paris-based International Chamber of Commerce arbitration court demanding up to $75 million, asserting that his management team had been wrongfully fired. (The Washington Post reported in January that the dispute had ended in a confidential settlement.) Trump’s team is still managing the hotel portion of the Ocean Club, for which it has a 40-year contract.

As the AP put it, “the Trump Organization’s adventures in Panama provide a window into how these traits have filtered into his business empire—and the style of management that could be expected in a Trump White House. Transparency and close attention to expenses are not strengths. Squeezing the most from contractual language is.” One retired American doctor who had purchased a unit told the AP that “I thought it was pretty safe, because we had Trump involved,” but that he’d since realized that “he’s a predatory businessman.”

The last time a member of the Trump family appears to have visited Panama City was in December 2015, when Eric Trump travelled there to attend the Ocean Club’s fourth anniversary party and “to strengthen and support the plans to improve the property in the near future,” according to a press release. In an interview with the AP that fall, the president’s son dismissed the troubles inside the building as a sideshow to what the Ocean Club was really about–“an amazing icon and, frankly, a great testament to America.”

Meanwhile, Martinelli spends his time in Miami meeting friends, posting photos of himself working out at the gym, mocking current Panamanian president Varela, sharing his favorite songs like the Bee Gees’ “How Deep Is Your Love” on Facebook, and fulminating on social media about his political enemies. But he hasn’t mentioned Trump on Facebook or Twitter since the inauguration.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(89)