Virus poses major harm, but also opportunities for Latino businesses

As the U.S. economy remains largely shut due to the coronavirus pandemic, many businesses are facing an uncertain future. In Los Angeles County, where Latinos own as much as 29 percent of all businesses, many are fighting to stay afloat, while a few struggle to meet unprecedented demand.

According to its executive director, Lilly Rocha, the Los Angeles Latino Chamber of Commerce has about 1,700 members “that encompass everything from small mom-and-pop-size operations all the way up to large corporations.” However, she says the majority “are small businesses with maybe less than 10 employees.”

Several factors put Latinos in particular at risk for economic hardship. “A lot of the jobs that Latinos have are not jobs that you can do remotely,” Rocha says, adding, “We’re talking about people who don’t make a lot of money and don’t have a lot of money saved up.”

When it comes to the COVID-19 shutdown, Rocha says the loss of business is compounding the challenges that Latinos already face in the economy. “Everything that we know of that was affecting Latinos before, it’s just exponential now.”

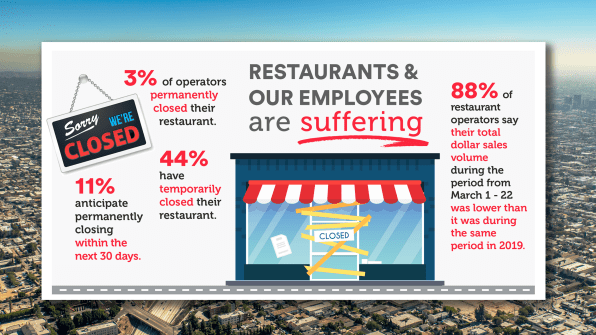

That’s especially true of the food industry, which has been hit particularly hard. “Restaurants are probably the most affected,” she says. According to data gathered last month by the National Restaurant Association, 44 percent of U.S. restaurants are temporarily closed while three percent are permanently and another 11 percent anticipate being forced to close permanently within the next 30 days.

Alberto Sanchez says sales at his long-running Chico’s Mexican Restaurant in Los Angeles’ Highland Park neighborhood have dropped by more than half since the lockdown began in March.

In an area where gentrification and rising rents have displaced many Latino businesses, Sanchez feels lucky that rent is not his biggest worry. “I’ve been here 28 years, so thank God I don’t have a big rent compared with a lot of other people,” he says. However, ordering the basic supplies to run a restaurant carries more risk now. “We prepare food and we don’t know if we’re going to sell it,” says Sanchez. Mainly, he is just hoping to “survive until May 15,” when Los Angeles County’s stay-at-home order is currently scheduled to end. Could a longer shutdown put him out of business? “I don’t even want to think about that,” says Sanchez.

Everything that we know of that was affecting Latinos before, it’s just exponential now.”

Lilly Rocha, executive director of the Los Angeles Latino Chamber of Commerce

Things are even more precarious in another sector of the food industry. “My business is pretty much shut down now,” said Daniel Garcia, a street vendor who sells tacos in the Westlake neighborhood of Los Angeles, in a translated statement. For Garcia, the economic shutdown comes at a pivotal time, when recent changes to city and state laws have legalized sidewalk vending. While the city had planned to allow vendors a six-month grace period to pay permit fees and obtain approved carts, a motion in response to the COVID-19 crisis called for immediate enforcement of street vending permits.

“Getting a permit for food vendors is really complicated because they have to follow county health code regulations,” says Carla DePaz, who is director of community organizing at the East LA Community Corporation, an economic and social justice group that advocates for street vendors. “It requires them to have a legal vending cart. It requires them to have commercial kitchen or commissary space for their cart and to prepare food.” According to DePaz, the vast majority of L.A.’s street vendors have not been able to secure permits yet for a variety of reasons, and are therefore barred from vending.

According to Garcia, before COVID he was saving up to buy an approved taco cart and secure his permit to sell food. But now that’s on hold, and without the ability to work, those savings are depleted. “I didn’t pay my rent in April. I have no idea how I will pay in May or even June,” says Garcia. “I’m worried about having to pay my back rent in the future. According to DePaz, many street vendors are unable to pay rent.

“Since we don’t know when this is going to end, we’re very worried about the debt that people are going to accumulate as street vendors,” she says. Despite the risks of encountering law enforcement or being exposed to the coronavirus, some street vendors are still attempting to eke out a living. “There are some people who are trying because they have no other choice,” says DePaz. “We’ve been encouraging vendors to practice precautions like everyone else.”

COVID-19 is also taking a toll on Latinos outside of the food industry. Jorge Tello, owner of La Casa Del Mariachi in Boyle Heights, is a well-known tailor who specializes in crafting the elaborate suits worn by mariachis. Because of the coronavirus shutdown, he is out of work. “The business has been closed for three weeks now,” said Tello in a translated statement.

As customers dwindle and expenses add up, Tello is trying to stay afloat. “I make mariachi suits and I regularly work for the Los Angeles Unified School District. Now that schools are closed, I won’t have work to do,” he says. “In my case the business is my own, but not the location. . . There’s no business to make money to pay the rent.” Although Tello acknowledges that going out of business due to COVID is within the realm of possibility, he is also wary of government assistance programs. “I see it as another extra expense, because sooner or later I will have to repay this ‘support,’” he says.

In certain other sectors of the economy, business isn’t slow at all, and Latino business owners are struggling to keep up with unexpected and quickly shifting demand. Lila Don is the CEO and founder of SafetyVibe, a company that supplies personal protective equipment (PPE) for construction and related industries. SafetyVibe had already been selling masks and gloves for construction workers, but now it is scrambling to stock medical PPE amidst the COVID-related shortage.

“Because of the demand and because we’re a certified small business for the state, we are getting requests from different departments to see if we can help with the masks and the gowns and the gloves,” says Don, adding, “The quantities are huge because of the shortage. We’re trying our best to help by going outside of our supply chain to get a bunch of this stuff imported from overseas.”

For Don, keeping up with the surge in demand hasn’t been easy. “It’s a challenge for me since I’m a small business [and] I’ve got to pay upfront,” she says. However, it does mean that her staff can continue to work. “I have my staff working remotely, but I also still have my drivers and my operations and warehouse staff coming into work — properly protected, of course, and following CDC guidelines.”

Being forced to adapt quickly to a new business model is a common theme among L.A.’s Latino businesses during COVID. Alberto Sanchez has shifted Chico’s to takeout orders and deliveries via such services as Grubhub. “We’re trying to adjust and do what people feel comfortable with,” he says. Meanwhile, says DePaz, some street vendors have started “selling face masks or selling household cleaning supplies.” Her organization has explored the idea of having street vendors serve as “health ambassadors” who could be paid by the city “to distribute hand sanitizer and other things folks need right now.”

However, DePaz says the best thing local governments can do for street vendors is provide cash assistance. “It’s really important for street vendors and other informal undocumented folks, to have access to cash,” she says. DePaz says her organization is also pushing the city to return the fees that have already been paid for pending street vendor permits. “That’s money people could use right now,” she says.

As Lilly Rocha points out, even bigger firms are at risk of going under. “It’s very precarious,” she says. But despite the uncertainty of the coming weeks and months, Alberto Sanchez is trying to keep a positive outlook. “We’re waiting to reopen the doors for the people to come in,” he says.

(75)