What Are The Congresspeople Whose Districts Will Be Underwater Doing To Stop Climate Change?

Climate change was once an abstract global issue, easy for locally elected politicians to ignore or question. But scientific forecasts are far more specific today. It’s not just the world or a country or a particular state facing unprecedented floods, droughts, or heat waves—climate change is happening right in our backyards.

Scientists have come out lately with a string of dire of sea level rise forecasts. Six feet of sea level rise by the end of the century has been thought to be an extremely unlikely scenario—yet new estimates of melting rates in Antarctica now show it’s possible. Importantly, new research has also focused on localizing how different sea level rise scenarios will translate at a very local level, down to the county or even zip code.

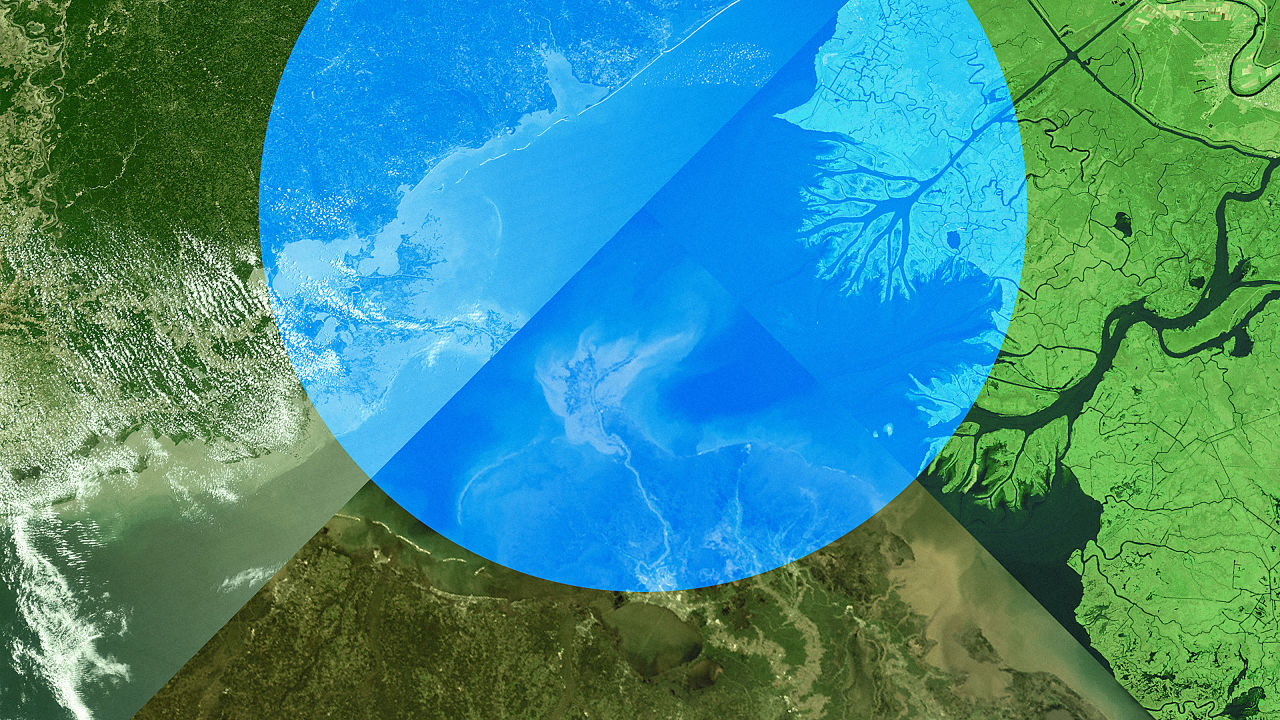

Co.Exist has examined recent studies that show how specific U.S. coastal cities and towns will be damaged with rising seas. From New York City to Maryland, many coastlines in the nation are at risk, but two stick out as supremely vulnerable—southeast Florida and the Louisiana Gulf. Due to geography, geology, and population, these are the places that will have large masses of land disappear, endangering property, roads and bridges, wildlife, causing havoc on people’s lives, and making storms more deadly and destructive. The first sea level rise relocation in the United States is now planned in southern Louisiana, for example. In Miami Beach, homeowners expect their property values may start to decrease fairly soon (already, getting flood insurance is all but impossible). Given that the scientific consensus is that much of these districts will be underwater, do the statements and positions from politicians in southeast Florida and the Louisiana Gulf match up with the level of threat to their constituents?

All politics is local, the saying goes. It should now include climate politics. So we looked at these districts representatives in Congress, since these politicians are elected by very specific localities, yet they also have a key role in deciding national policies to rein in greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to warming impacts. It’s clear that even in the extremely partisan environment of Congress, the realities of climate change are starting to hit home in at least some of the Congressional districts that are under the greatest threat—even if that means bucking Republican orthodoxy to start trying to save these districts.

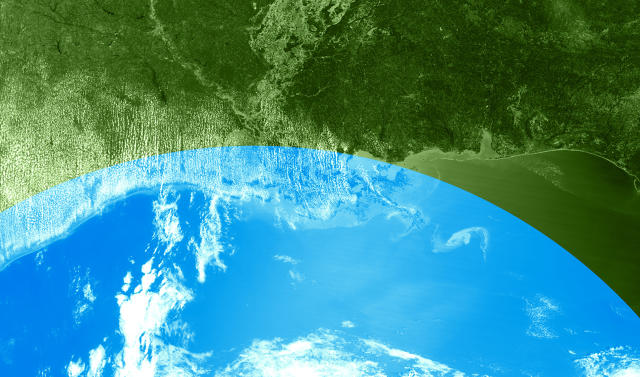

Southeast Florida

This region is at the forefront of climate change. Miami-Dade and Broward Counties have the two highest populations in the United States that could be displaced by rising sea levels by 2100, according to a recent study in the journal Nature. In addition, a report by Climate Central, a nonpartisan research organization, found that of all zip codes in Florida, Key West comes in third place for the highest number of people, housing units, and property value within three feet of the high tide line (behind Miami Beach and Palm Beach). Frequent floods rising to this level are “near certain” this century, the report says. After only 14 inches of sea level rise, it says, a flood to 2.2 feet in Key West would be an annual event—considering most of the islands are less than 6 feet above sea level, huge swaths of the islands would be wiped out and the rest would be so frequently flooded that living there could be miserable.

In the face of this reality, a fear of flooding has sunk into the psyche of many Florida legislators in Congress, from both parties.

Freshman Republican Congressman Carlos Curbelo, whose District 26 encompasses the entire southern tip of Florida, including much of the Everglades and all of the Florida Keys, has been a rare voice among House Republicans who accepts the science of climate change and calls for action to address it. Last year, Curbelo—also one of the youngest members of Congress—formed the bipartisan Climate Solutions Caucus with a fellow Florida Democrat, and in December, he was one of 10 Republicans to vote against his party in its resolution to gut President Obama’s rules to regulate emissions from new power plants. He noted at the time that sea level rise was a “clear and present threat” to Florida’s way of life and that 40% of the state’s population was at risk. (He did, however, vote with his party to oppose regulating emissions from existing power plants.)

As far as concrete actions, the Climate Solutions Caucus hasn’t done much yet, though it only just had its first meeting. Curbelo highlights his own efforts to increase funding for Everglades restoration, create more affordable flood insurance, and reform the existing National Flood Insurance Program—which is currently in deep debt and unable to keep up with claims payouts.

In many ways, because of the dynamics of the House—where Republicans have blocked all climate change action, Republicans who break with their party have much more power to make change. Southeast Florida’s Republican Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, a senior House member whose district includes large parts of Miami-Dade county, has also gone that route, becoming the second Republican to join the bipartisan Climate Solutions Caucus. (She has also signed on to a resolution introduced in September by New York Republican Chris Gibson that declares climate change could have an “adverse” impact on the nation and Congress should work on remedies. This seems like a bare minimum kind of statement, but so far only 12 Republicans have signed on.)

Democrats in southeast Florida’s Miami-Dade and Broward counties are also vocal about climate change and act with their party to support climate change actions, though none have taken significant leadership on the issue. Democrats Debbie Wasserman Schultz, Frederica Wilson, and Lois Frankel represent some of the most districts with the most potential damage from sea level rise. Large parts of Wasserman Schultz’s Miami Beach, for example, could be underwater in less than 50 years—and property values will be affected much sooner than that. At least she can talk about sea level rise statistics like a scientist.

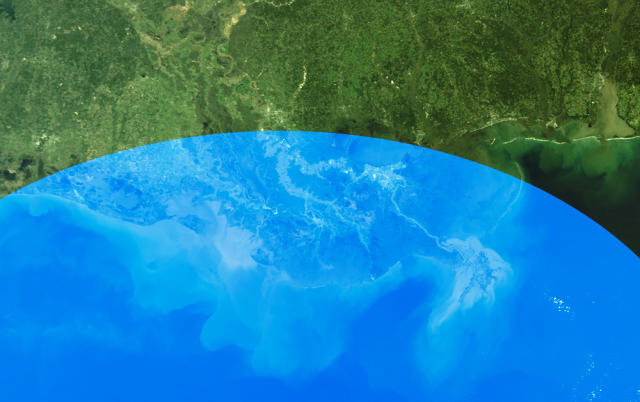

Louisiana Gulf

New Orleans and the entire Mississippi Delta region are doomed locales—the first climate refugees in the lower 48 states, who are being evacuated now, hail from this zone. An October 2015 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that no matter what is done to curb climate change today, virtually all of New Orleans will be flooded eventually (unless it is saved by improved flood control systems). Under a three-foot-sea-level-rise scenario, a study in Nature Climate Change ranked Orleans Parish as the fourth county in the nation in terms of total population at risk from floods by 2100, just after nearby Jefferson Parish, which came in third. About 18% of the projected population of each was at risk of being displaced, the study found.

Like southeast Florida, the region is doomed if we continue business as usual. The big difference here is that the region’s economy is centered on oil and gas drilling, making climate change-friendly policies harder, politically. Officials of both parties are, therefore, interested in protecting the fossil fuel industry to varying extents. But even though climate change isn’t a cause these politicians love to discuss, they do have to deal with its effects, such as skyrocketing flood insurance rates and sinking state highways. And that reality means that in southern Louisiana, there is one more rare Republican willing to acknowledge climate science.

In flood-prone District 6, which covers an area from Baton Rouge to the Gulf, first-time Republican Congressman Garret Graves believes climate change is real. As former state coastal restoration commissioner, he had previously grappled directly with sea level rise. He has been one of the few great hopes in his party for environmentalists. But that hasn’t quite panned out, as the region’s oil interests (and his Koch Brothers’ donations) have taken precedence in his voting record. He still will acknowledge climate change—which is more than many of his colleagues—but he has blocked the Obama administration’s efforts to regulate emissions from power plants, calling them too expensive.

On the other hand, we have District 1, which includes Jefferson Parish, the shores of Lake Pontchartrain, and the petroleum center Port Fourchon. The district is represented by Steve Scalise, the third-ranked Republican in the House. Scalise is heavily funded by the oil industry. Although he has lobbied for funding to raise the elevation of the flood-prone state roadway LA-1, and recently posted on Instagram about “historic flooding events” in his district, he has long decried “global warming alarmism” and questioned the science of man-made climate change. In his role as House whip, he has led Republican efforts in the House to block the Obama administration’s climate rules.

Meanwhile, Democrat Cedric Richmond, who represents New Orleans’s District 2, is a lot better, though he is far from a climate change leader. Yes, he has a pretty good record voting for measures to address climate change (he has also voted to support oil and gas interests). But considering the threat his city faces, he has not been vocal or exhibited much leadership on the issue. A search of his website reveals that even in his efforts to reform and expand flood insurance and disaster assistance, he has not made any effort to talk about climate change or sea level rise impacts.

What’s clear is that, in at-risk coastal areas, climate change can’t be ignored, even by partisan ideologues (unless you’re Rep. Scalise). But the rest of the country that isn’t living under the threat of immediate flooding also needs to come to understand the gravity of the situation if Congress is ever to take the actions to curb greenhouse gas emissions that are needed to lead the world to a safer future. With open Senate seats in both Florida and Louisiana, the 2016 election should reveal whether climate change can become an election issue that matters in the states that could be flooded by the century’s end.

Related Video: The Cop21 Climate Talks And How They’ll Affect Your Business

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(24)