Whatever Happened To Dual-Screen Smartphones?

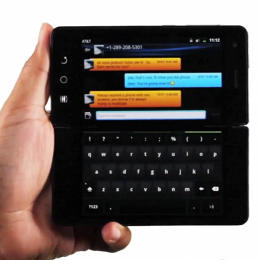

Back in 2011, an unknown smartphone brand called Imerj began to show off a slick prototype for a dual-screen smartphone.

The device unfolded like a clamshell laptop, allowing users to type on one screen while interacting with apps on another. In portrait mode, users could run two apps side by side, with swipe gestures to pass apps back and forth between the two displays.

Unfortunately, the product never shipped for a variety of reasons, and since then, no one’s released a phone with side-by-side screens outside of Japan. But if anything, the idea makes more sense now than it did five years ago. Smartphones continue to cannibalize tablets and laptops, as we spend more time texting, reading, socializing, watching videos, and playing games on the one device that’s most readily available. As such, we demand ever-larger smartphone displays, to the point that we can barely fit them in our hands and pockets anymore.

Surely, we’d go even larger if we could. But instead of making a single-screen even larger, perhaps the time is right to add a second one.

Failed Attempts

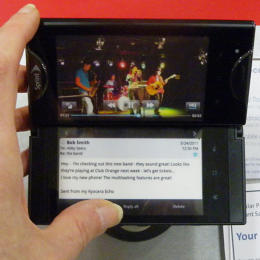

Imerj wasn’t the first attempt at a dual-screen Android phone. That honor goes to the Kyocera Echo, which sold as a Sprint exclusive in 2011.

The Echo launched with a lot of fanfare, but it had a number of problems. When unfurled, the two screens had a thick bezel between them, tarnishing the tablet-like experience Kyocera was aiming for. The extra display also consumed a lot of power—a point that Kyocera seemed to acknowledge by shipping the Echo with an external battery pack.

Worst of all, the Echo lacked the software to support its ambitious hardware. Out of the box, only a handful of apps supported side-by-side use, and Kyocera’s attempt at an app-developer program went nowhere. Perhaps Kyocera could have established an ecosystem had it committed to the dual-screen concept over the long term, but the Echo ended up being a one-off experiment. (A Kyocera spokesman initially seemed willing to have the company answer questions about the Echo, but then stopped responding to my emails.)

Imerj’s take on the dual-screen phone was more refined, but also more ambitious. The prototype was conceived and built by electronics manufacturer Flextronics (now known as Flex), with the original goal being to create a phone that could dock into a desktop workstation, says Sean Burke, who ran Flextronics’ computing division at the time. To enable multitasking on the workstation, the Imerj team adapted the Linux kernel to run multiple Android apps side by side, along with a full Linux desktop. The dual-screen phone evolved out of that effort.

“Because we had resolved the whole aspect of doing multitasking and multi-displaying, we could actually do dual screen and have the combination of making it a full-sized screen across two screens, or running multiple apps at the same time and maintaining full Android compatibility,” Burke says.

But while Burke maintains that the device was ready for production, Flextronics was unable to drum up interest from electronics brands. Motorola, for instance, was busy with its own laptop docking system on its Atrix smartphones, while Sony didn’t want to diverge from its existing three-year product roadmap (which included a dual-screen tablet but no phone). Cisco, which had been dabbling in consumer electronics with its acquisition of Flip camera maker Pure Digital, liked the Imerj idea but decided it was too aggressive a leap into the smartphone business, Burke says. A “big retailer in the U.S.” also opted against making its smartphones after initially seeming interested in the project.

Meanwhile, Flextronics itself was reluctant to go directly to market, Burke says. Like many Android phones, its design would likely have infringed on patents from companies like Apple and Microsoft, who at the time were some of Flextronics’ largest contract customers.

“Contract manufacturers tend to be risk-averse. We don’t want to piss off anybody, because everybody’s a potential customer,” Burke says. “When it got down to the wire of, do we go or don’t we go, the board and CEO just said it’s really not worth it.”

Still, Burke—who is now a corporate vice president and general manager at AMD—is convinced the idea was a good one. As proof, he sent me a focus group video in which people are marveling over the two screens (“As soon as he opened it up like that, I was like, wow,” one participant says), and claims that some of the Imerj team members still use their prototypes.

“I thought it was much more natural to the way I use my computer,” Burke says, noting he’d use the second screen to reference a Word or Excel document while writing an email, or use the extra screen as a touch keyboard.

What’s Holding Back The Extra Screen

Although no major phone makers have attempted a dual-screen smartphone since Imerj wound down, the pieces are starting to fall into place.

Android, for instance, will support two apps running side by side in the next major version, dubbed Nougat. Burke says while phone makers would still have to define how dual-screen interactions work, native multi-window support should make things easier.

As for hardware, the borders around smartphone screens have gotten much narrower over the last five years. (On Xiaomi’s Mi 5, for instance, the bezel is practically nonexistent.) And while a dual-screen phone would still draw extra battery power and require a thicker design, display technology and power efficiency have improved to the point that a doubly thick phone doesn’t seem like a big tradeoff. Lenovo’s Moto Z, for instance, is a mere 5.2 mm thick. If you stacked two of them together, they’d still be slimmer than an original iPhone. (Hey, maybe one of the phone’s Moto Mods attachments could be a slide-out secondary display.)

That’s not to say the concept is without its design challenges. The borders around smartphone screens won’t go away completely until displays become fully bendable—an advancement that’s still many years away—and Burke says he’s still not sure how well a dual-screen design would accommodate third-party cases.

Technology analyst Patrick Moorhead points out another issue. Hinges, he says, are notoriously difficult to design when trying to strike a balance between sleekness and sturdiness. As an example, he points to Windows tablet-laptop hybrids from a few years ago, which were either too flimsy or too clunky. It took PC makers a few years to get it right.

“I think that’s a mechanical problem we haven’t fixed yet,” Moorhead says. “I feel like we’re probably three years away from being able to fix that, but somebody has to come out with it first in order to iterate off it.”

Perhaps that’s the biggest challenge of all: To design a dual-screen phone, some hardware maker will have to part with nearly a decade of design conventions and take a big risk. But for Burke, who never envisioned that giant screens would instead become the norm, a second screen makes at least as much sense.

“I do like the bigger screen, because I’m old and my eyes aren’t as great,” Burke says. “But it’s like, how big can you get without being stupid?”

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(29)