What’s Next For Precision Medicine?

Berg Health’s cofounder and chief executive Niven R. Narain is used to being laughed out of rooms, given his interest in bringing artificial intelligence into the drug development process. But things have changed, he says, thanks to growing excitement around the practice known as precision medicine.

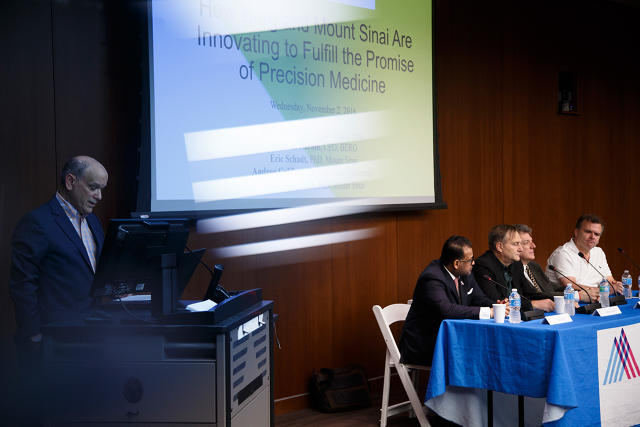

This afternoon, at the Fast Company Innovation Festival, Narain spoke on a panel on the topic of bringing advanced technologies to medicine with industry experts from Mount Sinai and Columbia University. Precision medicine is an all-encompassing term, which broadly refers to the idea of treating patients in a more personalized, targeted way rather than taking a one-size-fits-all approach to disease. The White House announced a $215 million investment in precision medicine earlier this year; if nothing else, it generated a lot of hype.

“This is a time of unprecedented change,” Narain said to kick off the discussion, which took place at The Hess Center for Science and Medicine at Mount Sinai. “The paradox is that worsening financial challenges for patients are occurring at a time of transformational advances in biomedical research.”

Berg Health, which is based in Boston and is backed by Silicon Valley real estate billionaire Carl Berg, is hoping to cut the costs and time associated with drug discovery and development—roughly $3 billion and more than 10 years—by fusing methods from genomics, proteomics, and artificial intelligence to uncover novel drug targets. (All of these have been tried individually, but Berg hopes his approach will stand apart because it combines the tools.) Berg wants to offer new drugs at a reasonable price point so they’re not out of reach for most patients.

For Berg, the potential roadblocks are seemingly endless: In health care, bringing together disparate data sources is a nightmare, not to mention the regulatory protocols. And the financial incentives are a mess. Most hospitals are still fee-for-service, meaning they get paid based on costly tests and procedures rather than on patient outcomes. (That’s starting to change, thanks in part to the efforts of the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services, but it won’t happen overnight.)

Here’s what the panel had to say, both about the promise of precision medicine and the potential hurdles:

Show Me The Data

All of the experts on stage agreed that collecting one source of patient data, such as genomics, usually isn’t all that useful.

Eric Schadt, director of the Icahn Institute for genomics and multi-scale biology at Mount Sinai, urged the medical sector to find better ways to engage with patients. It’s not enough to sequence their DNA: To develop predictive models, he said, researchers will need to grab data from the patient’s electronic medical record, their labs, as well as procedures and pharmacy data. They might also tap into health-related data streaming from devices through services like Apple’s HealthKit.

The trick will be to offer patients some kind of value in exchange for this data, as well as to ensure them that it will be used in an ethical manner. Schadt made the point that most of us willingly hand over personal information to Google in exchange for a nifty search engine and email service, but not for medical research. “What’s in my Gmail is more personal than what is in my medical record,” he said. “So in medicine, we have to figure out the trade-off of what’s the right amount that you have to give someone so they’re willing to consent.”

One important development making all of this possible is the added clarity around consent and data-sharing from institutional review boards (IRBs) and regulators, although there’s more to be done in that regard. Eric Nestler, professor of neuroscience at Mount Sinai, made the point that we also need more substantive laws to protect patients from being discriminated against: GINA, the genetic anti-discrimination law, for instance, doesn’t protect people from being denied life insurance, long-term care, and disability on the basis of a genetic test result.

Do We Need More Drug Therapies?

Another important question raised is the topic of drug development: Do we need new therapies to treat disease, or should we be focusing our energies on making better use of the existing ones?

New algorithms are increasingly being used by researchers to match patients’ tumors with optimal drug treatments, according to Andrea Califano, chair of Systems Biology at Columbia University. “We take the entire collection of thousands of FDA-approved investigational compounds and run them through the same algorithm,” he said.

Califano might determine that a cocktail of different drugs could work for a certain cancer patient, while others only require a single therapy. That’s what he sees as the near-term promise of precision medicine: “We don’t need to develop a lot of new drugs,” he says. “We should be able to treat a lot of different cancers.”

But Narain believes that we need to do both, to reposition existing drugs and develop new ones. His company is working to find new therapies by taking a differentiated approach, one that he described as “biology first.” The process begins with the extraction of biological data from cancerous and healthy tissue samples. The company then uses artificial intelligence to suggest possible drug treatments, and models that in mice.

But…

One word: interoperability.

The big challenge with bringing together patient data is that information stored in electronic medical files cannot easily be stored or shared. This is an ongoing nightmare for those in the medical sector, due in part to the fact that health systems don’t want to lose (profit-driving) patients to another facility. (Check out my multi-part series on the topic.)

When asked about whether this situation would be resolved in the near future so that health information could be standardized, no one on the panel seemed particularly optimistic. “It seems far away,” said Schadt. (Note: Cleveland Clinic recently named FHIR, an approach to this crisis that acts as a translator for electronic health record systems that don’t normally play well together, as one of its top breakthroughs of 2016.)

For that reason, the panel seemed to agree that artificial intelligence is no quick fix for systemic issues. We need to aggregate the data first and then marry AI with existing tools. “Disease is about demystifying what we don’t know,” Narain concluded.

At the Fast Company Innovation Festival, experts spoke on a panel about bringing advanced technologies to medicine.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(20)