When refugees need emergency help with a language barrier, this app connects them to a translator

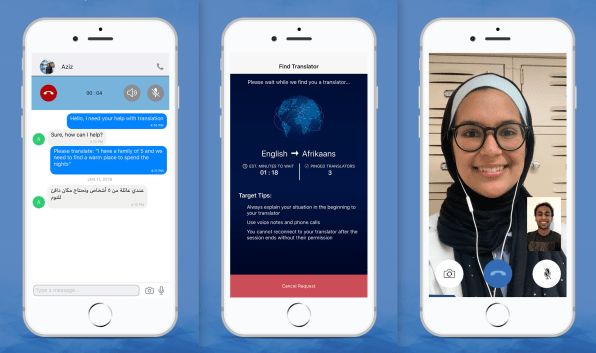

When a boat carrying 12 refugees capsized in early 2018 on its way to Greece, a Greek nonprofit team saw the accident–but they weren’t allowed to bring their boat into Turkish waters to make the rescue. They also couldn’t speak Turkish, so when they called the Turkish Coast Guard, they couldn’t communicate. Then someone pulled out an app on their phone, and minutes later, they were connected with a volunteer who works as a designer in Los Angeles and happens to speak Turkish.

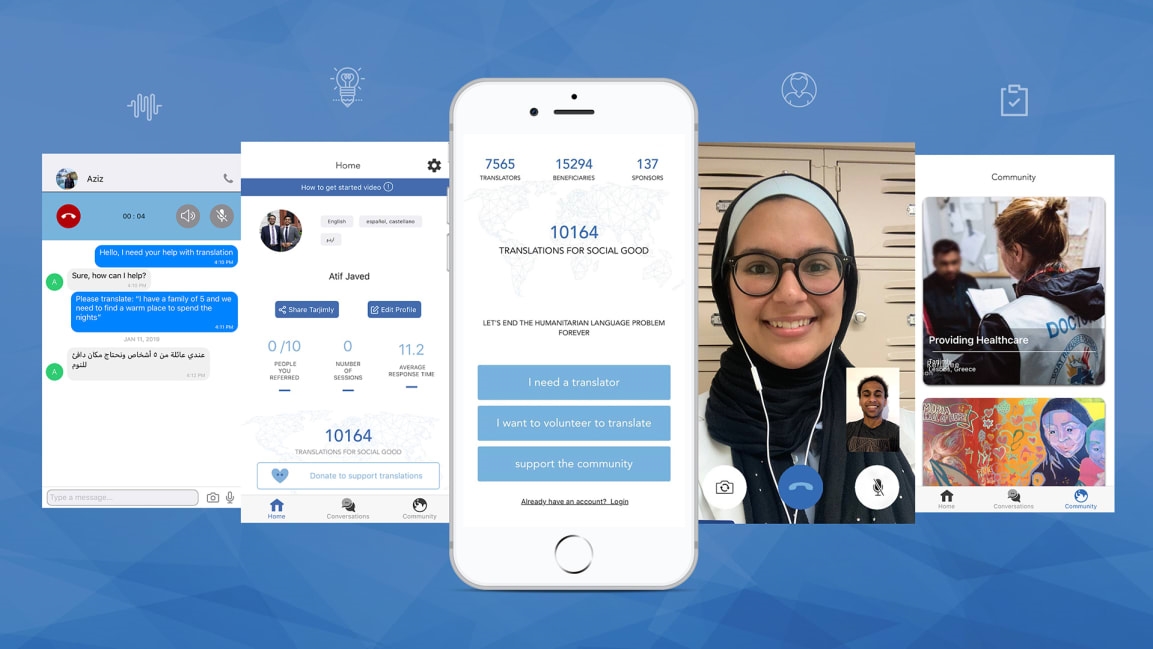

“She came home from work to her apartment and got a ping saying, ‘Hey, are you free for 10 minutes to help?’ All of the sudden she was part of the rescue,” says Aziz Alghunaim, one of the cofounders of Tarjimly, the startup nonprofit that first launched a Messenger bot two years ago to quickly connect volunteer translators with refugees. (The name Tarjimly means “translate for me” in Arabic.) The volunteer called the Coast Guard, and a half-hour later, the refugees’ lives were saved. The service has now been used more than 10,000 times, and now the nonprofit is making it more accessible by launching new iPhone and Android apps that it hopes will reach more people.

The app started as a side project for Alghunaim and cofounder Atif Javed when both had recently graduated from MIT and moved to Silicon Valley to take more typical tech jobs. Javed’s own grandmother was a refugee, and when his family moved to the United States, he used to translate for her; both founders had started thinking about the need for translation in the current refugee crisis as students, and were increasingly disenchanted with standard tech work. “I wanted to be able to work on something that would not just be technology for the sake of technology or technology that’s just helping rich people in the world, but really helping people that truly need it,” says Alghunaim.

“It all started with us saying, let’s test this idea as fast as we can,” he says. “And the idea was simple: Can we use people’s skills–who are on the internet and know multiple languages–to completely eradicate the idea that a refugee cannot get help because they don’t speak the language of the aid workers?”

When Trump announced the first travel ban in January 2017–blocking refugee resettlement and citizens from seven Muslim-majority countries, and leading to an immediate need for translation at airports–the founders decided to share the app early. The response was immediate; within a couple of days, around 1,500 people had signed up to volunteer. Javed and Alghunaim decided to quit their jobs and launch the nonprofit.

The developers started with Facebook Messenger after realizing that refugees were already widely using it. They were able to test the viability of the concept: Would volunteers try it once or want to come back? Would enough people volunteer? Would the humanitarian sector trust the service and want to use it? They quickly saw that it was working. The platform now has more than 8,000 translators who speak more than 90 languages, and can be used in nearly any situation where someone trying to help can’t communicate with someone in need–as in a medical appointment where a doctor can’t talk to a refugee–and where a traditional translation service is unavailable.

The new mobile app is designed to go farther. Voice calls, for example, were hard to incorporate into the Messenger app. While refugees were already using Messenger, it’s not an ideal tool for humanitarian workers who might work for large organizations with specific security requirements for technology, or who might not want to require workers to use Facebook. The standalone app can incorporate new features, like an educational tool that can help someone improve their translation skills. With the new app, the nonprofit is hoping to sign up a million volunteers.

The app can also help in situations beyond refugee settlements and borders. Nonprofits that work with non-English-speaking domestic workers in the United States, for example, are interested in using the service. A resettlement agency recently used it to help a Swahili-speaking family sign up for food assistance in the U.S. Another agency used it to help a Spanish-speaking mother who had just given birth in a hospital that had no Spanish-speaking translators on hand. “We started this because of the refugee crisis because of that pertinent need,” says Javed. “But really, we’re now seeing the impact that has on the entire humanitarian space.”

(20)