Why becoming a single-income household was the best thing for my family

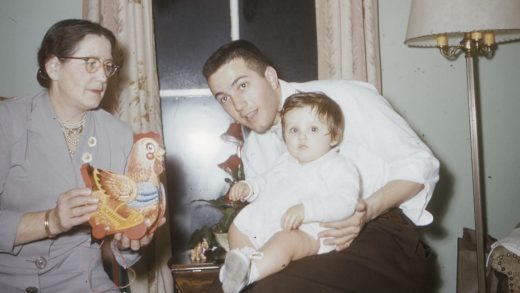

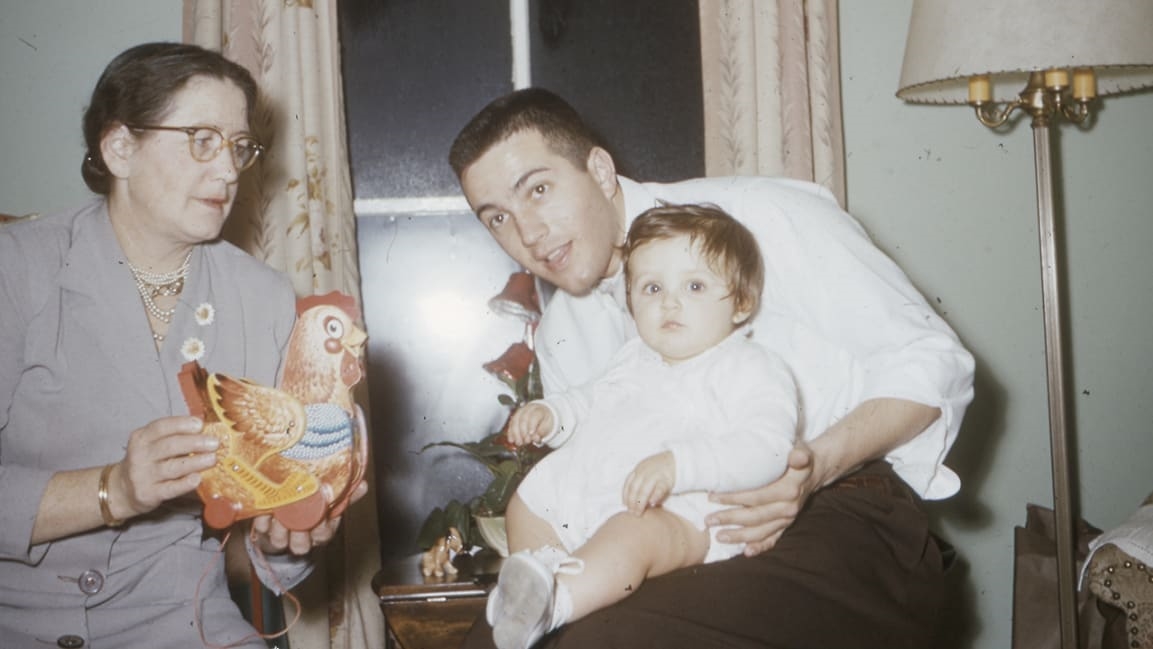

Eleven years ago my husband decided to chart a new path, and it had a positive impact on my career.

My husband made the brave choice to stay at home with our son. I call his decision brave because while 48% of working dads would like to join my husband as a stay-at-home father, few actually do. I live in Colorado, where we have a population of 5.6 million, and yet only 26,879 are stay-at-home dads.

Why so few? My intention here is not to analyze this question. Rather, it’s to explain how the second shift of housework and caregiving has fundamental economic undertones that impact everyone.

The abridged answer to why we see so few stay-at-home dads boils down to identity and isolation.

Our collective definition of what it means “to be a man” says that “good fathers” go to work to provide for their families’ financial security. Veer from this definition and fathers put their identity at risk. They also face isolation. Eleven years ago when my husband would take our son to Gymboree or music class, he was often the only man in a room of stay-at-home moms and female nannies. He didn’t have peers to talk with about the loneliness of charting a new path. None of his friends understood the struggle of putting a career on hold for family. But he did it anyway because it was the right thing for us–now a family of four–to do.

My husband did something else honorable, too. He reduced the second shift for me. Over time, he took on more tasks at home so I could focus on the best economic return for our family, which was building my career.

While I earned an executive MBA alongside maintaining my role as an executive at a Fortune 500 company, he understood that my time away was for the greater good of our family. Five years ago while I was leading a global team, I needed to visit five countries in the span of a month. It meant I was gone for over a week, home for about a week, and then gone again for over another week. At the time my children were 2 and 6. There was never a conversation about how my children would get to school, who would do the laundry, or who would prepare dinner for the family. My husband did it.

I’m telling you this because my husband’s unpaid labor is a partnership that supports me to be a better breadwinner mom. Our story is a lesson in economics, too. Sharing unpaid work is not simply an issue of fairness. It’s fundamentally an issue of economic growth, and I brought the data to prove it.

Sharing unpaid work boosts the economy

To understand how economic growth and unpaid work relate to each other, we first need to understand the demographics of our current labor force.

Only 50 years ago, less than half (44%) of prime working-age women were in the labor force. Today, their participation has jumped to 75%, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. We need to acknowledge that women and mothers have been increasing their labor force participation for decades now, and their wages aren’t just for purses and shoes. In fact, our economy is $2 trillion larger today than it would have been if women had not increased their participation and hours since 1970.

According to the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee, moms are the breadwinners in 40% of households in the U.S. with children, and 37.5% of those are married breadwinners, like me. They have husbands who either work part-time or are stay-at-home dads.

In other households, mom may not be the breadwinner, yet her family depends on her wages for their economic and social well-being. For the average household with a mother working outside the home, mom’s earnings account for 40% of total family wages. A report from the National Bureau of Economic Research revealed that since a parent’s income influences developmental factors such as children’s future earnings, whether or not they go to college, and even if they become teen parents, mom’s wages cannot be taken lightly.

Mothers’ increased labor force participation and share of household earnings coincide with another trend among fathers. Nearly half (48%) of working fathers say they would prefer to stay home with their children. Yet of all U.S. households with children under the age of 18, only 6% have a dad who stays home, according to an analysis of data collected jointly by the U.S. Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

This indicates that our labor force is undergoing a transformation. Unfortunately, cultural expectations of what it means to be a good mom or a good dad haven’t kept pace. With more moms providing for an increased share of their families’ economic well-being, the assumption that they still must do the majority of domestic labor–the second shift–causes more than just friction on the homefront.

The second shift is not a “he versus she” issue

Despite their increased role in the workforce, women continue to hold responsibility for the majority of domestic duties. Cooking dinner. Cleaning bathrooms. Doing laundry. Compared to their husbands, the second shift has women working an extra four days each month on domestic tasks even though men have tripled the time spent with children since 1989.

From apps that help couples equitably split up chores to practical online guides, there’s no shortage of resources for those feeling the weight of the second shift. While they provide couples with tools to foster equitable households, we must proceed with caution. We cannot frame the second shift as a “he versus she,” “husband versus wife” issue. It’s not. It’s an economic issue that I experienced firsthand as a breadwinner mom with a stay-at-home husband.

As we witnessed with the $2 trillion women have added to the U.S. economy since 1970, there’s a tangible, economic benefit to eliminating the second shift: a larger labor pool and the related economic boost from gender equitable teams.

Beyond those advantages, we know that when we distribute housework and childcare equally, women’s ambition for top executive roles goes up nine points. If unpaid labor were allocated in a gender-neutral way, output would increase by 5.4% per hour. And because men run households differently than women, children benefit from the diversity of gender-neutral housework, too.

Two recommendations to eliminate the second shift

We have the power to take steps toward eliminating the second shift and create more economic opportunities for our society. Here are two ways to get there.

1. Change maternity and paternity leave to caregiver leave

There is a six-point gap between companies that offer a paid maternity versus those that provide paid paternity leave, according to the Society for Human Resource Management. The best option for employees and their families is paid caregiver leave. It’s gender-neutral, providing both moms and dads equal opportunities to stay home.

Paid caregiver leave could also mitigate mishaps such as what happened with JP Morgan. The company recently settled a U.S. parental leave discrimination case that was biased against dads: Men at the company had missed out on their fair share of parental leave. The employee dads who missed out on parental leave will split the $5 million settlement.

2. Close the working moms pay gap

Working moms earn 71¢ on the dollar compared to their male peers. This year, Working Moms Equal Pay Day is June 10, 2019–six days before Father’s Day and 69 days after the aggregate Equal Pay Day. The next time we recognize Moms Equal Pay Day, let’s do so from an understanding of what it really means to be a breadwinner mom and how those extra 69 days are holding our economy back.

What a more equitable future could bring

This past May, my family went on our annual Memorial Day camping weekend. Everyone has jobs around the campsite. In an unprovoked spark, my 12-year-old son jumped up and declared, “I’m going to go help Dad with the dishes.” We didn’t assign genders to dishwashing responsibility, it was ultimately about the family, our team. I’m proud that my son views the dishes as “family work” rather than “women’s work.” We are all on the same team so we all chip in equally, regardless of gender.

(58)