Why the prosperity gap in the U.S. is stuck–and how to fix it

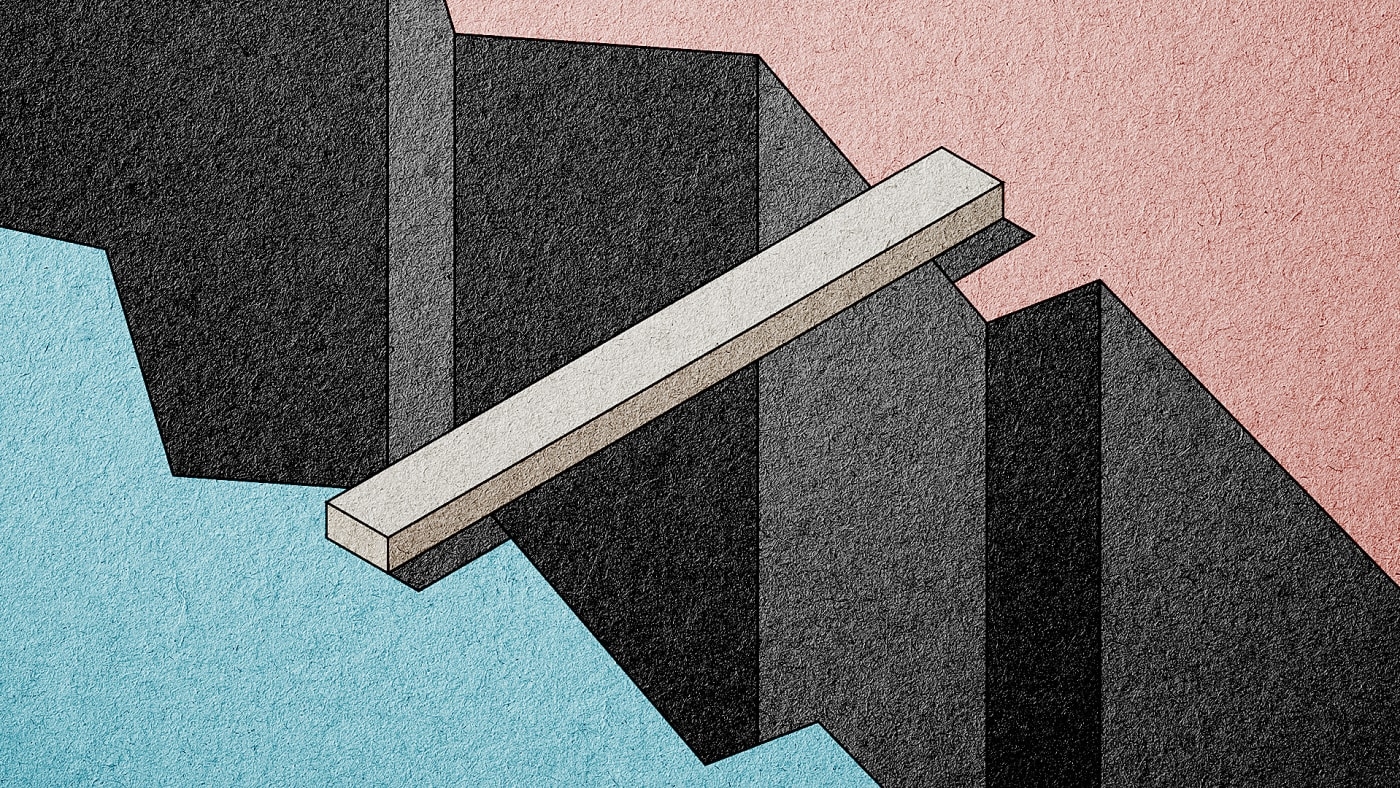

Decades ago in the United States, if you lived in a place that was struggling economically, you could reasonably assume that within a few years, it might turn around. This was because of a phenomenon known as convergence, which holds that growth rates in economically distressed areas tend to exceed those in areas that are already prosperous, so that in the future, the gap between them narrows.

According to new research from The Hamilton Project, an economic research group within Brookings Institution focused on inequality and economic disparities, this dynamic held sway through the middle of the 20th century. “The Southeast rose from 50% of average national income in 1930 to 86% by 1980; during the same time, New England fell from 130% to 105% as the rest of the country caught up,” writes Hamilton Project director Jay Shambaugh.

Now, that’s no longer the case. Convergence, Shambaugh says, ground to a halt in the 1980s, and the gap between richer and poorer counties has mainly widened in the decades since. The decline of manufacturing jobs (and the labor unions associated with them) has certainly played a role, Shambaugh says, as have natural and man-made disasters ranging from Hurricane Katrina to the water crisis in Flint, Michigan. And as hard-hit communities struggle to catch up, wealthier places like New York City and San Francisco, bolstered by industries like tech and finance, have boomed, widening the gap between the two and making mobility more difficult.

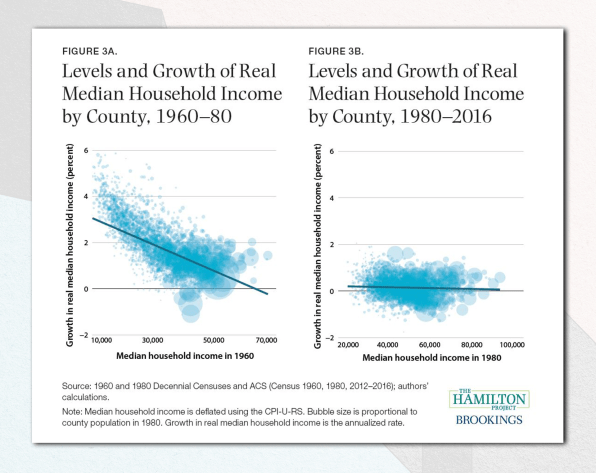

To measure how regions and their levels of prosperity have changed over time, The Hamilton Project developed the Vitality Index, a measurement of several factors that indicate how a county is faring. While many similar measurements, like the Economic Innovation Group’s Community Distress Index, exist, The Hamilton Project assigns a weight to each metric in accordance with its importance to overall outcomes. Median household income is weighted at 45%, poverty rate at 24%, life expectancy at 13%, prime-age employment to population ratio at 9%, housing vacancy rate at 5%, and unemployment rate at 4%.

With several exceptions–among them the upper Midwest, which has seen some counties’ vitality scores rise, troublingly, due to the increased presence of fracking and mining industries–vitality scores have held constant across the country since 1980, as has the gulf between prosperous and struggling regions.

But The Hamilton Project research and development of the Vitality Index isn’t merely to show how little progress has been made over the past several decades. Rather, it’s designed to call attention to the need for new tactics and energy around how to support growth and vitality in distressed regions. The research opens a new book produced by The Hamilton Project, called Place-Based Policies for Shared Economic Growth. The title, Shambaugh says, is loaded. “Economists have often been skeptical of place-based policies,” he says. Policies designed to target the specific needs of a county or region are often difficult to push through politically. And, Shambaugh says, efforts to improve vitality in struggling places are often countered with the question of if it’d be more worthwhile to just encourage people to move to booming places instead. As housing costs have grown out of reach in those areas, though, migration has become less possible, and rates have consequently slowed.

“When you think of all these things together, it starts to make you think that whatever your views on place-based policies were a decade ago, you should probably at least reconsider them now,” Shambaugh says.

No one policy, Shambaugh says, will in itself re-energize the convergence trend that disappeared in the 1980s, but the book outlines several avenues to effect change in some capacity that, in aggregate, might help close the gap between prosperous and struggling regions.

One, proposed by David Neumark, professor of economics at the University of California, Irvine, advocates for a fully federally funded job creation program in regions struggling with high and persistent rates of unemployment. Rather than providing incentives for employers to create jobs in struggling communities like the U.S.’s “enterprise zone” program does, the Rebuilding Communities Job Subsidies, as Neumark terms the proposal, would use federal funding to intentionally create high-wage jobs for people through nonprofit partners. After 18 months of employment through the nonprofit, people would transition to private-sector jobs, which would also receive some measure of federal funding to boost pay. The combination of job training, local partnerships, and overall economic support, Neumark writes, is designed to create lasting impact and set struggling counties back on the path toward convergence.

Another group of professors propose a tactic that would encourage local research universities to extend their influence in the surrounding labor market by training workers and ramping up local sourcing and procurement to boost the economy. And Tracy Gordon, a tax policy expert at the Brookings Institution, proposes that the federal government overhaul the $700 billion it currently allocates in grants to states to ensure that it’s going toward evening the playing field between states with strong financial capacity, like California, and those that are struggling, like West Virginia.

“That addresses the big-picture question–are states getting the money they need?–while other proposals, like Neumark’s, are much more targeted to smaller areas on the ground,” Shambaugh says. That combination addresses the fact that economic disparities in the U.S. are largely concentrated by region, but within those regions, drastic differences still exist. Fulfilling the recommendations in Place-Based Policies call for more targeted, thoughtful, local investments from companies and institutions, and also significant movement in how federal government disperses its funds. The former, ideally, should be achievable. The latter–like the recent proposal from Elizabeth Warren to dedicate $450 billion in federal funding toward the affordable housing crisis–will be contingent on a sea change in power at the national level, but for the time being, provides a road map for how we can set the country back on a path toward greater economic parity.

(23)