With $20M from Scale, Textio Envisions ‘Augmented Writing’ Everywhere

In a prime example of the promise of artificial intelligence to improve human capabilities, rather than just replace them, Textio is bringing its “augmented writing” technology to e-mails, sales and marketing communications, and other forms of business writing, and just raised $20 million to do it.

The Seattle startup, which until now focused on improving the performance of job posts and other recruiting-related communications, announced that Scale Venture Partners led a Series B funding round, with prior investors Bloomberg Beta, Cowboy Ventures, Emergence Capital, and Upside Partnership also participating. Textio has now raised $29.5 million in total funding. The company raised its Series A round in late 2015.

The new investment will support the vision ex-Microsoft senior managers Jensen Harris and Kieran Snyder set out with when they founded Textio nearly three years ago: “bringing augmented writing to all kinds of writing,” says CTO Harris.

“Augmented writing is going to be used for everything,” he says. “It’s going to be a superpower. Once you have it one domain, you will feel naked without it in others.”

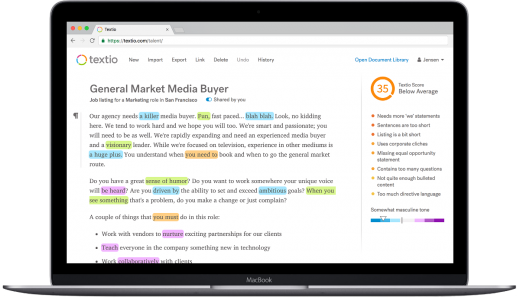

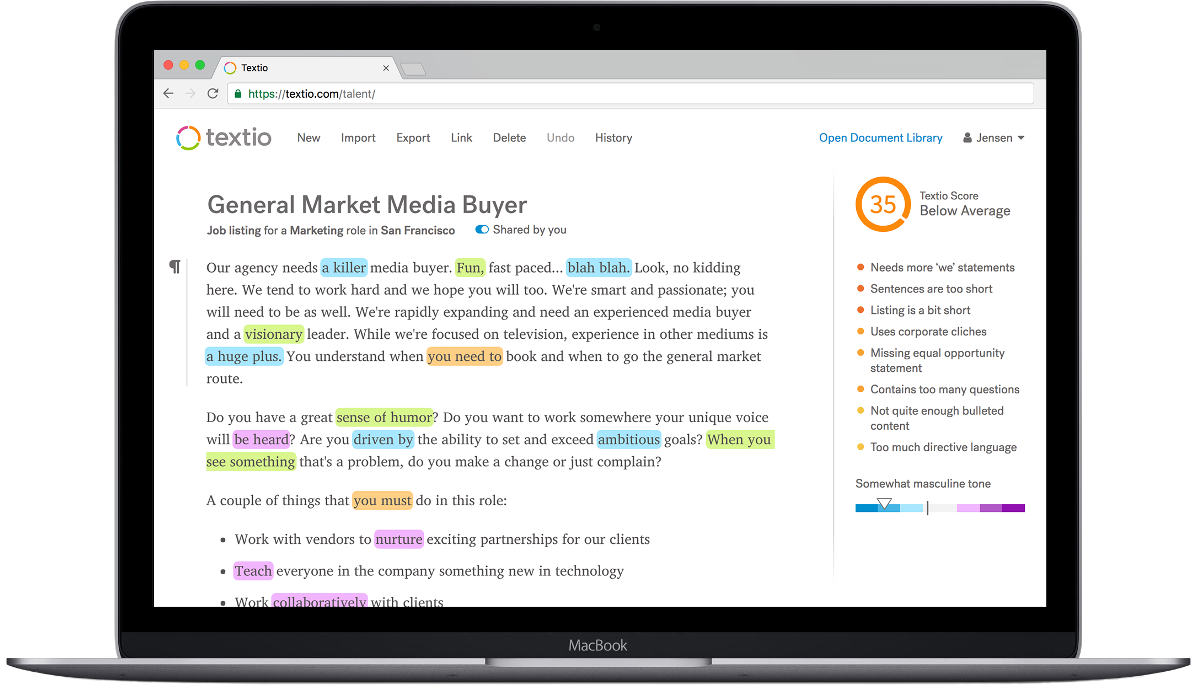

Textio goes much further than the grammar- and spell-check tools that have been part of modern word processing software for years (and indeed many, including Microsoft Word, now offer stylistic suggestions, too). Textio analyzes a draft job post and scores it based on expected performance, refined down to specific occupations and geographies. It recommends improvements that the human writer can make to produce an end product that’s more likely to resonate with the intended audience.

The company’s initial expansion plans include improving writing in e-mails, and sales and marketing communications—types of business writing adjacent to the recruiting- and HR-related communications where Textio has gained initial traction. (Its customers include Apple, BP, Expedia, Cisco, and Johnson & Johnson).

The additional investment will allow the company “to quickly do more than we would have been able to do otherwise,” Harris says. The staff of about 35 is expected to grow by another 20 to 25 positions this year, Snyder says.

A machine learning algorithm is only as good as the data it’s trained on, and Textio has implemented a program to source millions of job listings each month, and their outcomes—how many applications the listing attracted, and how long it took to make a hire—from its customers. Textio gives its enterprise customers a discount on its services for sharing their data, and they in turn benefit from a learning machine that’s tuned with their own data.

“This has been a key thing that has driven the platform and the business forward,” says Snyder, Textio’s CEO.

As Textio expands, it will need to gather similarly large datasets, with outcomes attached, of e-mails and sales and marketing communications in order to build its models for improving writing in these and other domains.

Snyder says the new domains are “a natural” direction for expansion because companies have this data. Whole businesses are built around measuring the performance of sales and marketing materials, and “even a moderately sophisticated organization” measures the open rates of e-mails it sends out. Many also measure the sentiment of responses its e-mails receive.

Stacey Bishop, partner at Scale Venture, is joining Textio’s board of directors, bringing with her deep expertise in marketing technology and automation, Snyder says.

As A.I. spreads across the economy, it brings with it fear that it will take human jobs—and not just the blue-collar work of manufacturing and transportation. Do marketing copywriters need to fear Textio?

Textio’s founders say no. The company’s technology is about augmenting human writing, not automating it. “If everything were automated, even in just the narrow job-post domain where Textio began, everything would sound exactly the same,” Snyder says. “We’re never going to get to the point of taking the [human] writer out of the equation.”

The value that Textio brings is in guiding human writers to the formatting, structure, length, and language that performs the best with their intended audience. Companies use it to fill open positions faster and to attract more women to their applicant pools by filtering out gender-biased language from job posts.

The tech industry has A.I. fever, with companies large and small touting buzzwords such as A.I. and machine learning (so much so that Textio’s own analysis of the most effective terms in tech recruiting find A.I. falling out of favor, Snyder says). Textio’s founders say their company is building the real thing.

“Textio is a purpose-built A.I. company,” Harris says. “We haven’t changed since the beginning.”

Machine learning and natural language processing technology are inherent in the company’s product, rather than bolt-ons to a photo sharing or food delivery app that’s trying to sound trendy. “It’s not an ingredient we’re adding to something else,” he says. “It’s who we are and what we founded the company to do.”

Harris bristles at the cheapening of the terminology being used willy-nilly today. Slapping the label “A.I.” on a basic prediction made with a machine learning algorithm, a dataset, and a service from one of the cloud computing giants “sells very short the actual promise of a system like augmented writing,” in which learning technology works alongside the human writer to bring out the human’s potential, he says.

The way Textio does this is important, too, and provides a glimpse of a world in which the so-called “black box” problem in A.I.—that an intelligent machine can tell you what to do based on the data, but not exactly why it’s making a given recommendation—is solved. “It’s not enough to say, ‘Here’s a job listing. Sorry, it sucks. Good luck,’” Harris says.

Textio analyzes thousands of attributes of a given document to determine what is causing it to score poorly. Then it imagines better versions of the document, essentially foreseeing which of myriad possible variations in the writing will bring the whole to “the most elevated state,” Harris says. Finally, it guides the human writer toward the best improvements, without cutting the human out of the loop.

(27)